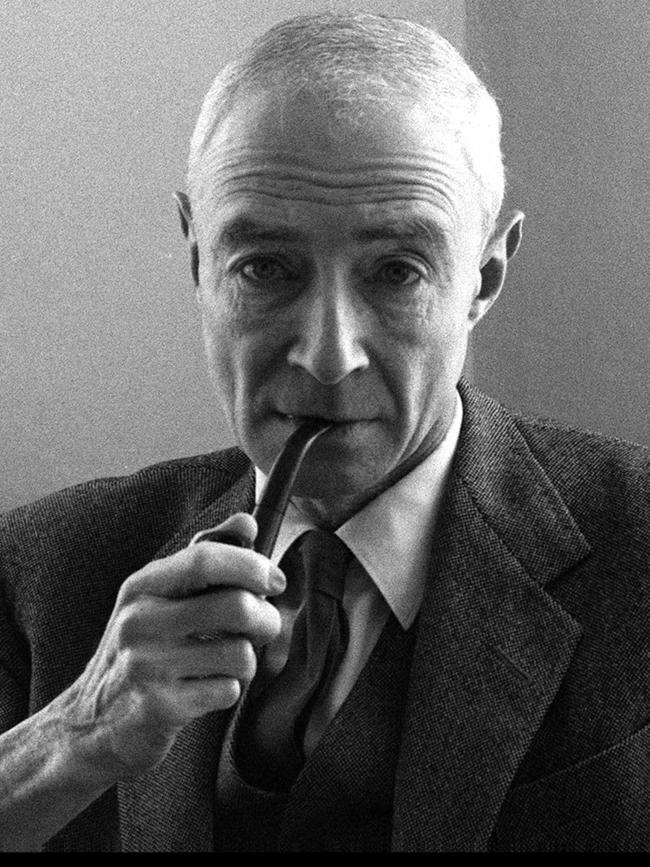

Robert Oppenheimer, Harry Truman and the a-bomb legacy

Oppenheimer wanted Truman to understand the need to control this awesome and destructive weapon and limit its future use. It was a doomed mission. Truman could not believe what he was hearing.

He referred to Oppenheimer, known as the “father of the atomic bomb”, as a “son of a bitch” and “crybaby” scientist. He told aides he never wanted to see Oppenheimer again.

The extraordinary scene is dramatised in Christopher Nolan’s compelling new film, Oppenheimer, with Cillian Murphy portraying a deeply troubled Oppenheimer and Gary Oldman portraying a rather stunned Truman.

After all, Oppenheimer had not only led the development of the bomb as part of the Manhattan Project but also recommended it be used as a weapon of war.

The film prompts a reconsideration of Truman’s ultimate decision to use the bomb twice in August in 1945 – the only time such a weapon has been used in combat.

It also serves as a powerful and timely reminder of the continued proliferation of nuclear weapons and the moral questions they evoke over whether they should be used again.

Truman later said authorising the use of the atomic bombs was “the worst thing I ever did” and recognised the outcome was a “terrible” tragedy that killed more than 100,000 people and left many scarred, poisoned and traumatised.

The destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was near total. But Truman never expressed remorse for his actions. Indeed, his decision to use bombs to end World War II was the right decision then and it remains the right decision today.

There should be no hand-wringing over that most difficult of choices faced by any US president and perhaps any political leader in modern times. It weighed heavily on Truman and Oppenheimer.

The development of the atomic bomb was a race against Nazi Germany. That context is important. It was critical that Adolf Hitler’s war machine did not obtain this weapon.

Truman, who had been elected as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s vice-president in November 1944, was not told about the bomb until after he became president in April 1945. This is extraordinary. Given FDR’s failing health, Truman should have been briefed.

Nolan’s film documents the establishment of the team of physicists led by Oppenheimer tasked with developing the bomb at Los Alamos, New Mexico, which culminated in the Trinity test in July 1945. A government committee was established to provide advice to Truman on using the bomb, which included input from Oppenheimer and other scientists who had worked at Los Alamos.

They unanimously advised Truman to use the bomb against Japan as soon as possible, without specific warning and in a way that would demonstrate its destructive power. They advised against a “technical demonstration”, such as over a deserted island or barren location, as it would not bring the war to an end.

Japan had ignored a warning to surrender issued by the Allies at Potsdam, and Radio Tokyo had broadcast an intention to keep fighting at all costs.

Truman considered the only other option to end the war: an Allied invasion of Japan. Known as Operation Downfall, the overall plan would have been bigger than D-Day. Estimates of casualties ranged up to and more than one million. That invasion would have involved Australian troops.

In Evan Thomas’s new book, Road to Surrender: Three Men and the Countdown to the End of World War II, the author writes that even after the atomic bombs were dropped, there was a determination among Japanese military and political leaders to never surrender.

Thomas estimates that had Japan continued to fight the war, perhaps millions more would have died in an invasion.

With access to the diary of Japanese foreign minister Shigenori Togo, the book chronicles how he helped convince Emperor Hirohito to surrender, even though other members of the Supreme War Council preferred to fight on, prepared for an Allied invasion, and would continue until there was nobody left to fight. Talk of surrender was forbidden.

The notion that he had helped develop a weapon to save Western civilisation but that same technology could now be magnified and used to destroy all of civilisation tortured Oppenheimer for the rest of his life. He knew that after the Trinity test – brilliantly captured in the film – the world would never be the same again.

But Oppenheimer, like Truman, never apologised for his role in developing the atomic bomb or expressed regret that it was used in Japan.

He did, understandably, wrestle with the humanitarian consequences of his actions. This, and how he was treated later during the 1950s, is at the heart of Nolan’s extraordinary, exceptional and poignant film.

In the years after the war, with talk of developing a hydrogen bomb that was 1000 times more powerful than the atomic bomb, former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt asked if humankind was creating something that it ultimately could not control.

This is an important question that remains just as relevant, especially given many countries now have weapons of infinite destruction in their arsenals.

We continue to live with the existential threat of nuclear war.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has seen the Doomsday Clock tick closer to midnight. The only agreement on arms control between Russia and the US, New START, is suspended.

Other non-proliferation efforts have stalled.

There are about 12,500 nuclear warheads today, and each one is far more destructive than the atomic bomb.

Having witnessed this power unleashed with catastrophic consequences, though justifiable and necessary, Oppenheimer hoped this indiscriminate and inhumane weapon would never be used again.

Indeed, these weapons of mass destruction should never be used again, and we should redouble international efforts to avoid the risk of nuclear conflict by error or by design.

When J. Robert Oppenheimer met Harry S. Truman at the White House in October 1945, the physicist most responsible for developing the atomic bomb told the president who made the decision to detonate it over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that he – Oppenheimer – had blood on his hands.