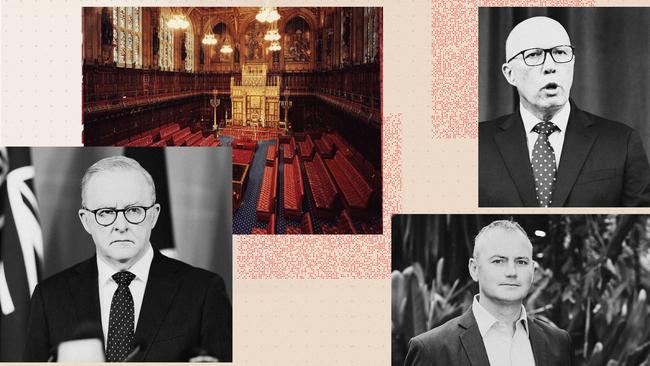

In the British parliament there is something called the Salisbury convention. Named after the Marquess of Salisbury and introduced in 1945, the convention guarantees that the House of Lords – where the government seldom has a majority – will pass legislation that was included in the winning party’s election manifesto.

It makes sense and helps to facilitate the democratic governance of the country.

We have nothing like that. Opposition and minor parties continually amend or defeat government legislation in the Senate regardless of whether the government promised at the previous election to make the changes the Senate blocks.

So, as we head for the next election, the major political parties should adopt an Australian version of the Salisbury convention – named after an Australian instead of the Marquess of Salisbury, of course.

That would mean if Labor or the Coalition won a majority in the House of Representatives, the winning side would be able to fulfil its election promises.

That would help assuage the cynicism of a public that had heard promises from politicians that were not delivered.

Sometimes election promises are not delivered because the government can’t get the legislation through the Senate.

I know what the counterarguments are going to be. The Senate, unlike the House of Lords, is elected. Yes, it is, but in a disproportionate way that does not reflect the opinions of the Australian public in general. It is gerrymandered in favour of the smaller states.

Opposition parties will claim that the promises of the winning party are flawed and that they themselves have some kind of a mandate.

Well, they didn’t get a majority in the House of Representatives, and that defines who governs our country. They can scrutinise, amend and even defeat legislation that is introduced but was not part of an election commitment.

But political parties that won elections should be held to account for their policies, for which the public had voted, by the Australian people at the subsequent election.

In the lead-up to the 2025 election it’s time we had a debate about this and seriously thought about it. After all, one thing is certain about the next election: neither the Coalition nor Labor will have a majority in the Senate.

Commentators also are speculating that the next parliament will be a hung parliament. I’m not sure. It is possible that the Labor Party or the Coalition will win an absolute majority.

Still, what could we expect from a hung parliament? That depends on the composition of the parliament. There are three possible scenarios to consider.

First, Labor wins the largest number of seats and has an overall majority with the support of the Greens. The Greens already have said they would never support a Coalition government. That’s an eccentric position to take if they wish to retain some negotiating clout.

Labor knows it will continue to govern with the support of the Greens no matter what.

The Greens may be able to sabotage particular pieces of legislation, assuming the Coalition in opposition agrees with them – and although that seems an unlikely proposition it can happen. But otherwise, their support for Labor is already given.

Second, it is possible that Labor and the Greens are not able to secure a majority and the teals backed by Climate 200, founded by Simon Holmes a Court, hold the balance of power.

The teals won’t tell you who they would support in motions of confidence and supply in that situation but my guess is that privately Holmes a Court would prefer a Labor government. But if the Coalition secures more seats than Labor they will feel under some obligation to support a Coalition government on matters of confidence and supply.

But here’s the rub. If the Coalition has the largest number of seats, it will have won those seats on a manifesto. It has not rolled all of this out yet but we do know it wants to move towards nuclear power, cut government spending, liberalise the industrial relation system, crack down on union rorts in the construction industry and so on.

But Holmes a Court and the teals are more of the green-left persuasion and they are likely to oppose all of these reforms. If they did, then a Coalition government would not be able to do many, if any, of the things it promised and that it regarded as necessary to revitalise Australia. The Coalition government would be hamstrung from the very beginning and after three years the public would rightly question what the point of it really was. After all, the government would have changed but nothing much else would have happened.

One solution to this is to ask Holmes a Court and his teals to make a commitment to an Australian Salisbury convention. They don’t need to tell us before the election who they would support in a hung parliament but they should make a commitment to facilitate the passage of legislation that would implement promises made during the campaign by the winning political party.

If they didn’t do that, the Coalition would be better off refusing to form minority government with the support of the Holmes a Court teals. It should make it clear that Labor should continue to govern and the teals should give Labor confidence and supply even if the Coalition had more seats than Labor.

In reality, the Coalition probably would take power if it could but it would be a very hard three years for it, and the Coalition’s future beyond that would be questionable, having failed to implement what it believed to be necessary reforms for Australia.

The third scenario is that the Coalition could form government with support of the genuine independents such as Dai Le, Rebekha Sharkie and Bob Katter.

That might be a bit easier for the Coalition, these independents being less left-wing than the teals and Greens.

Whichever way you look at it, the country would be much better off with a majority government, be it Labor or Coalition.

At the moment the public mood is one of deep disappointment with Labor so its re-election is not a given.

The immediate challenge for the Coalition is to make sure it offers an attractive package of reforms, including control of spending, an honest pathway to reduce energy prices, the curtailment of excessive union power, and a slashing of red and green tape for investors.