Planned changes would muzzle Crime and Corruption Commission

Official corruption is an insidious, consensual and clandestine activity that both the corruptor and the corruptee go to lengths to hide. The menace of corruption is global and has disabled governance and kept much of Africa, South America and Asia in poverty, and increasingly disables the West. Corruption in the public sector causes loss to state and national treasuries and robs the citizenry of their collective wealth.

Those elected to represent us, especially those holding ministerial office, have the capacity to vastly enrich themselves by corrupting government processes and must be subject to appropriate accountability mechanisms, even if that might be uncomfortable.

This proposal greatly weakens that accountability and its deterrence.

Much of the report of the Fitzgerald Inquiry, which in 1989 led to the creation of the CCC and exposed systemic political and public sector corruption in Queensland, would have been impossible under the proposed regime. The pattern of political corruption exposed by Fitzgerald ran from the then premier down. It greenlighted the systemic police corruption which bedevilled law enforcement in Queensland for decades.

Facing this restriction, the Fitzgerald Inquiry reforms would have been stifled and at best resulted in a few apparently disassociated prosecutions of police officers and/or politicians.

This is not mere speculation. There are in Queensland several examples to draw upon to illustrate that, by circumscribing corruption inquiries, the continuation of serious and systemic corruption has been facilitated.

For example, the corrupt system known as “The Joke” had existed in the Queensland Police Service from 1959. Alleged police corruption had been the subject of several ineffective formal inquiries before Fitzgerald. One was the infamous National Hotel Royal Commission convened in 1963 under then Supreme Court justice Harry Gibbs. At that time, The Joke was in full swing, and allegations of corruption were rife.

In a pattern that has been repeated many times since, police closed ranks behind those being investigated and gathered evidence to discredit those who made allegations.

The Gibbs Royal Commission naively limited itself to admissible evidence during the investigation stage (that is, evidence required in a courtroom). Despite finding that offences had occurred on many occasions, it shockingly concluded: “… there is no acceptable evidence any member of the Police Force was guilty of misconduct, or neglect or violation of duty …”, thereby subjecting Queenslanders to two more decades of depredations perpetrated by institutionally corrupt police.

Twelve years after Gibbs, a further inquiry headed by another Supreme Court judge, Geoffrey Lucas, was established as a result of the resignation of reforming police commissioner Ray Whitford in light of the acquittal of the self-confessed police bagman Jack Herbert. Its scope was limited by then Queensland premier Joe Bjelke-Petersen to reviewing law enforcement procedures despite Herbert’s admission of systemic police corruption. Judicial naivete continued, with the Lucas inquiry observing that it did not think “police officers generally would be so base that they would turn a blind eye to any crime committed by a fellow policeman”.

As Fitzgerald observed of the Lucas inquiry: “From this distance, it is possible to see how good motives and decent people were manipulated by and combined with others, less honourable, to produce a result which allowed corruption to expand and flourish.”

If Fitzgerald had faced the restrictions now proposed for the CCC, he could not have reported as he did. Indeed, without the public inquiry process being undertaken, without the evidence being disclosed, and without Fitzgerald’s observations and findings in his report being made public about the activities of politicians and police, there is every reason to believe there’d have been no reforms and Queensland would have remained mired in corruption.

Much of the Fitzgerald Report could not have been written.

For example:

- The involvement by ministers and others in suspicious financial transactions including political donations.

- The receipt of substantial unexplained payments, some in very large sums.

- The use of public monies to personally benefit ministers and their assets.

- The suspicious rezoning of land benefiting property developers apparently in return for financial considerations flowing to ministers.

- Evidence about the payment of corrupt monies to ministers.

A major finding of Fitzgerald was that the government had passively allowed police misconduct, including occasions when a blind eye was turned to police misconduct, sometimes to the benefit of politicians. What was also clear is that an active pursuit of corruption by the government would have helped contain, if not solve, the problem. The reform of the QPS under premiers Wayne Goss and Peter Beattie in supporting the endeavours of the CJC and the new police administration amply demonstrates this.

Much of that momentum has been lost under an increasing passive CCC, which appears to have wilted under the incessant, largely ill-informed criticism made of such anti-corruption bodies across Australia. This proposal risks further marginalising the CCC.

The abiding concern is that an ineffective CCC would provide a false sense of security while cloaking political malfeasance.

But perhaps the most absurd aspect of this proposal is the requirement to suspend reporting action critical of politicians until after conviction, which may or may not happen, and may vary from many months to several years after charges are laid (factoring in possible appeals).

A major function of the CCC is “to investigate complaints of official misconduct (including by politicians) referred to the body and to secure the taking of appropriate action in respect of official misconduct”. How can you frame the appropriate action if you cannot even articulate the problem? Why should politicians be exempt?

As Fitzgerald said: “However, the most important thing about the evidence … is the pattern, nature and scope of the misconduct which has occurred … Past misdeeds of individuals are of less concern, except as a basis for learning for the future … The pattern of which they form part … must now be changed.”

The concept of waiting several years to effectively report on a pattern of political corruption uncovered by CCC investigation until after convictions are achieved is, with respect, nonsensical.

Action must be taken in real time otherwise the process is neutered and illusory. Corrupt systems will remain in place, undiscovered participants will cover their tracks, and the plundering of the public purse will continue.

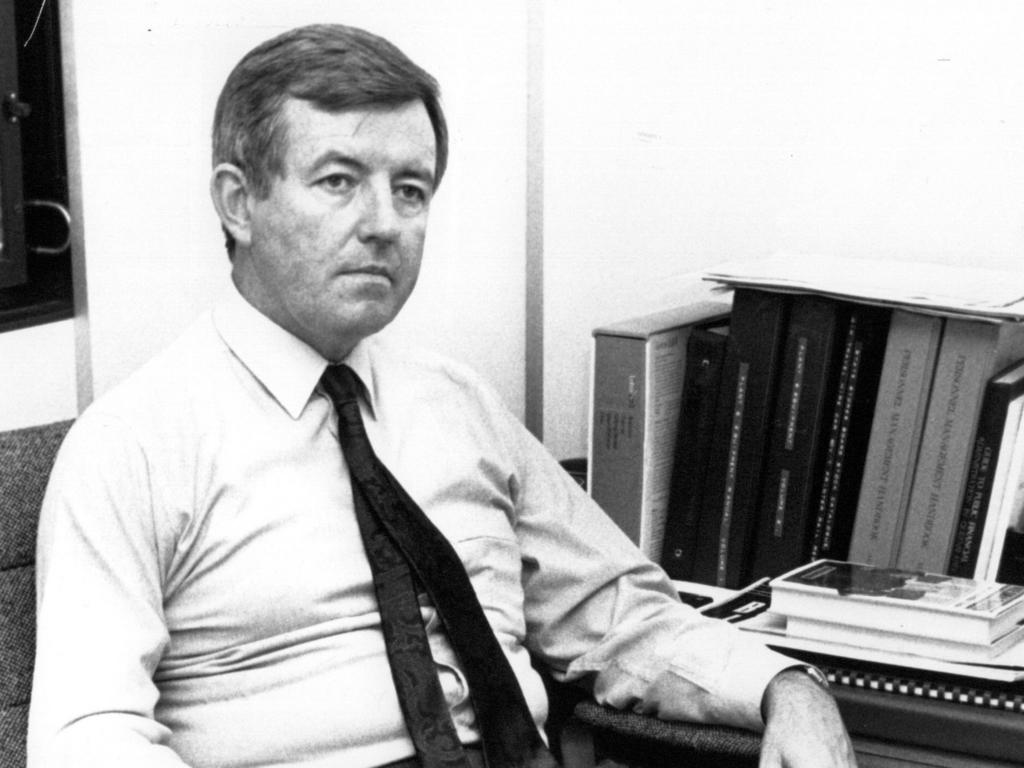

Mark Le Grand was inaugural director of the Official Misconduct Division of the Criminal Justice Commission from 1990 to 1999, the precursor to the Crime and Corruption Commission. He was a member of the National Crime Authority and former deputy commonwealth DPP.

The proposal recommended by former chief justice Catherine Holmes of Queensland that if there is no conviction of a politician, the Crime and Corruption Commission cannot make any “critical commentary, expression of opinion or recommendation based on their conduct” destroys much of the rationale for such a standing corruption commission.