Police escaped inquiry, but dark clouds formed over Sunshine State

Those decades of brazen corruption at the top levels of the administration of Queensland were born of the National Hotel Inquiry.

It was the biggest show in town since Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh visited Brisbane for a breathless 48 hours in March 1963.

As the royals were ferried around pretty Brisbane, waving to schoolchildren, unveiling plaques and observing the city’s finest dancing beneath City Hall’s great domed canopy, before being whisked off in their yacht Britannia to the sounds of brass bands, a shadow was looming.

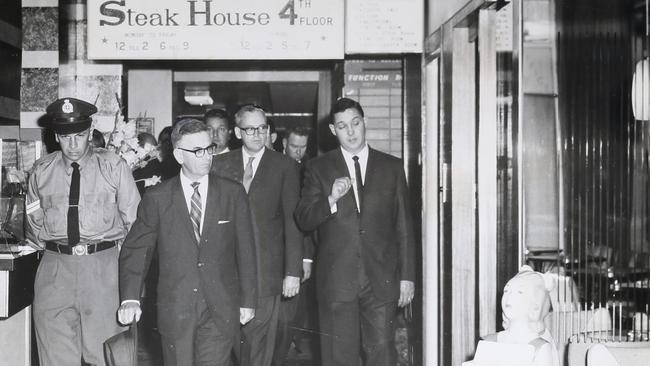

A commission of inquiry into police misconduct was set to open its doors on December 2 that same year in the District Court on George Street.

And the locals – perhaps still basking in the magical afterglow of a royal visit, that paragon of respectability and manners and protocol, that rare reminder of the apex of civility – were set to be treated to a litany of vile and salacious evidence over several weeks, an X-rated expose of Queensland’s filthy underbelly of call girls and orgies and crooked cops, centred on the city’s National Hotel, run by the Roberts brothers, at the northern junction of Queen and Adelaide streets.

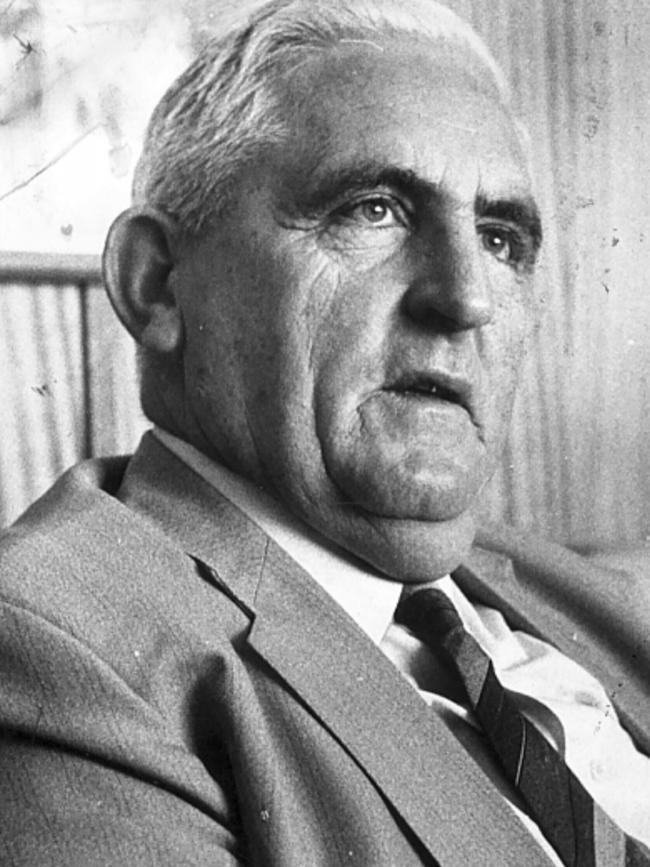

The National, or the Nash, was the pub of choice for the Queensland police elite, including commissioner Frank Bischof, a physically huge, uneducated good old boy who often held up the bar, attended innumerable lunches with the Roberts brothers that spilled into the evening and, as rumour had it, would bounce known prostitutes on his knee in full public view.

Stories of depravity and sin had oozed from the shabby multistorey hotel for years, undermining Brisbane’s quaint image as a god-fearing town of prim values. Indeed, as a host to royalty. Hadn’t Her Majesty just been here as recently as 1954?

But the commission, to become known as the National Hotel inquiry, refereed by the right honourable Justice Harry Gibbs, jolted the Queensland capital and its 659,000 inhabitants, and shook its innocence.

Sixty years later, the ramifications of that inquiry, and its findings, still tremor through government, the public service and the community, not overtly but as a permanent hum, a warning against the ease in which elected officers and officials could slip from righteous light into darkness. For some impacted individuals, it remains a daily source of pain.

The National Hotel Inquiry was the first official examination of police corruption in Queensland, and it failed miserably.

The late journalist Evan Whitton described the inquiry as “a cover-up”. Courier-Mail columnist Terry Sweetman wrote that “the failure of the National Hotel inquiry was the point at which public villainy became an industry” and that it had “condemned Queensland to decades of institutionalised corruption”.

A few years earlier, in 1960 a Hungarian immigrant, John Geza Komlosy, began work as a night porter for the National Hotel. On his first night, he noticed so much vice and drinking outside legal hours that he raised it with his superiors. His complaints were disregarded.

In the early 1960s, as Komlosy had observed, you were just as likely to see ladies of the night plying their trade in the bars of the Grand Central and the National, and slipping in and out of Lennons Hotel on their nocturnal assignations as you were the Salvation Army band playing in King George Square.

The sewer was starting to spill into the streets.

Then on October 29, 1963, the ALP state member for the inner-western Brisbane seat of Kurilpa, Colin Bennett – already a well-known lawyer in town – addressed a debate on supply and turned Parliament House upside down.

One observer described the moment as akin to someone lighting a string of Chinese firecrackers.

Bennett addressed the Queensland Police Force and its seemingly dysfunctional culture, before his dynamite sentence: “I do not wish to dally too long on this subject, but I should say that the commissioner (Frank Bischof) and his colleagues who frequent the National Hotel, encouraging and condoning the call girl service that operates there, would be better occupied in preventing such activities rather than tolerating them.”

A furious parliamentary debate followed. Bennett’s accusations were belittled as “the outpourings of a diseased mind”.

The subsequent public outrage was enough for conservative premier Frank Nicklin to call for public witnesses to step forward if they had anything that could corroborate Bennett’s claims. Only two obliged. National Hotel former employees John Komlosy and waiter David Young, who alleged he had personally served Bischof food and booze after hours.

On Monday, November 11, Nicklin announced a royal commission, beginning on December 2. Gibbs was named commissioner and the inquiry’s terms of reference were released. They were so narrow that Bennett said the government was “not game to have a full and open inquiry into police administration”.

What the public – and presumedly Gibbs – didn’t know was that in the month between the announcement of the inquiry and its actual first hearings, Bischof instructed his bagmen and attack dogs, the fabled “Rat Pack” of police officers – Terry Lewis, Tony Murphy and Glendon Hallahan – to find as much dirt as they could on potential witnesses such as Komlosy and Young and anyone else who might be able to shed a light on the nocturnal activities at the National. In addition, they needed to get the hotel’s sex workers on the same page when it came to giving evidence before Gibbs.

In short, their task was to tamper with witnesses and promote perjured evidence to subvert and influence a royal commission of inquiry.

They did their job well.

Young received a mysterious phone call before he gave evidence, warning him that if he went ahead, embarrassing information about his private life would be made public. Young discovered the caller was Hallahan. Similarly, Komlosy received a death threat letter. “If you value your life, say no more,” it said.

Young wasn’t intimated. He told the inquiry he had once entered a room at the National where three beds were being used by naked couples, and that one of them was notorious call girl Shirley Brifman. Under cross-examination, Young admitted to having sex with call girls himself. His reputation was trashed.

Komlosy faced accusations of fraud and being convicted under the Aliens Act in 1957, as well as details of his shaky employment history. Komlosy told the inquiry: “Not one gentleman has asked me anything about the National.”

The calling of witness Brifman was a sensation. She denied being a sex worker but accused Young in open court of committing an abortion on her, which he denied. This was a scandal.

Brifman, who died of an alleged drug overdose in 1972, just weeks before she was to give evidence against Murphy in his trial for giving perjured evidence at the National Hotel inquiry, confessed before she died that she had not only lied before Justice Gibbs, but had been coached in her evidence by Murphy and Hallahan before taking the witness stand.

“I talked to Tony before I went into the witness box,” she said. “I talked to him that night. He kept telling me things I had to say and things I didn’t have to say. (Hallahan and Murphy) … told me they would see the barrister and tell him the questions to ask me, and I was tutored on the questions and answers.”

The man himself, commissioner Bischof, gave evidence, proclaiming the whole business was the product of enemies and their vendettas against him. He told the court: “I think it was said 2000 years ago: ‘Forgive them, for they know not what they do.’ I say it again now.”

The inquiry ended on February 24, 1964, after hearing from 89 witnesses.

Gibbs produced his final report on April 10.

By the time the report was presented to premier Nicklin, the Komlosy family had already fled the country in fear of their lives.

Gibbs’ report concluded: “There is no acceptable evidence that any member of the police force was guilty of misconduct or neglect or violation of duty in relation to the policing of the hotel, or the enforcement of the law in respect of any breaches alleged or reported to have been committed in relation thereto.”

A police victory party was held. At the National Hotel.

Eyewitnesses said a drunk Bischof praised his Rat Pack for getting him “off this rap”, and told the crowd nothing would stop Lewis, Murphy and Hallahan from going to the top. They did, establishing a vast corruption network known as The Joke. Innocent people lost their lives. The careers of honest policemen and women were destroyed. Graft reached an industrial scale.

Gibbs’ tepid handling of Bischof and company had unleashed a monster.

In his book-length analysis of the royal commission, In Place of Justice, Brisbane writer Peter James concluded: “Whether a similar inquiry would be allowed to proceed as haphazardly and opaquely today, with as much lack of critical journalism, is open to debate … it is up to society whether it accepts suppression of truth and grossly compromised solution in place of justice.”

Later, Whitton was even more scathing. “Gibbs allowed the disgraceful impugning of witnesses, swallowed as fact a load of guff and perjured testimony, obtusely excluded evidence and was played for a fool by corrupt police. There is not the slightest doubt that Gibbs was a criminal. A cover-up of a crime is itself a crime.”

Gibbs would go on to enjoy one of the most distinguished careers in Australian law. He was appointed to the High Court in 1970, was knighted and in 1981 became chief justice of the High Court of Australia. He retired in 1987 and died in Sydney in 2005.

In 2012 the Supreme Court of Queensland Library established the Sir Harry Gibbs Legal Heritage Centre on the ground floor of the Queen Elizabeth II courts complex in George Street, Brisbane.

The centre states on its website: “As the state’s only dedicated legal history museum, the Centre offers a unique resource for visitors to the courts, school students and interested members of the public to explore Queensland’s legal past.”

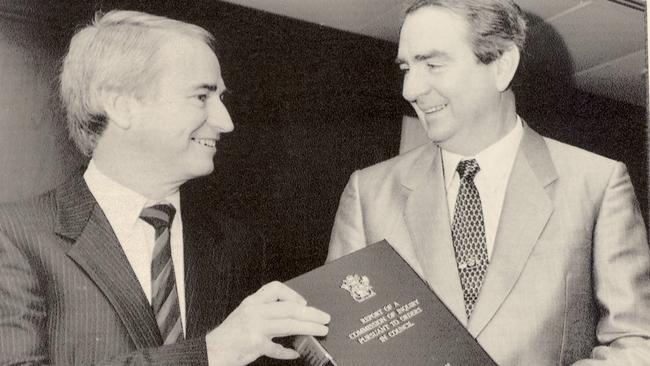

Tony Fitzgerald, who headed the successful Fitzgerald inquiry into Queensland police and political corruption (1987-89), which saw politicians and several corrupt police, including then commissioner Lewis go to jail, never blamed Gibbs for the National Hotel inquiry’s findings, deferring to the narrow terms of reference and limited powers Gibbs had to work with.

This did not stop rumours that the Rat Pack, who went to work undermining the inquiry’s witnesses, also collected a dirt file on commissioner Gibbs himself, and that it was aspects of that personal file and the threat of the information being made public that determined the inquiry’s outcome in favour of the police.

Those rumours have never materialised into fact.

As for the inquiry’s terms of reference, it was revealed years later by a Queensland public servant that they had actually been drafted by Bischof before Gibbs had taken his chair in the District Court on December 2, 1963.

The most potent outcome of the failure of the National Hotel inquiry was that it emboldened Bischof and his gang. They learned they could beat a royal commission. So began more than two decades of untrammelled and unprecedented corruption that devastated almost every crevice of Queensland life until the Fitzgerald broom.

As for the Komlosy family, they settled in what was then West Germany. By the early 1980s, at 58, Komlosy was working as a signal box operator near Osnabrück in northwest Germany.

He died alone on February 8, 2008, aged 84, following a stroke and is buried next to his wife, Else (who died of cancer in 1994), in the Wersen cemetery, just outside Osnabrück.

Their son Fred, who had loved his brief childhood in Brisbane, has never returned to the city. For years he kept a map of Australia pinned to his bedroom wall.

Fred, now 73, lives in the village of Hagen, 10km outside Osnabruck. He kicks a soccer ball around with his grandson. It reminds him of his years in Brisbane.

“At Acacia Ridge we had no club and no field,” he recently said. “Our playground was unsurfaced Watson Road, which left us kids with many a bruise, laceration or scratches. Nothing Dettol couldn’t repair.”

He said he still ruminated on the treatment of his father and the family during and after the National Hotel inquiry.

“It still bugs me 60 years later,” Fred told The Australian, “although my wife keeps telling me to forget and move on. We ended up as collateral damage caused by the crooked cops and other Queensland government organisations who wanted my father to be tarred, feathered and run out of town. At any rate, we ended up on the Eagle Street wharf one dark evening, boarded the Fairsea and that was the end of this chapter in my life.”

He believed he was denied a full and promising life in Australia, a country he quickly grew to love as a child, because of that moment.

“I have passed on what happened to my daughter who has become a teacher,” he said.

“Among other things (she) teaches young people about freedom, democracy and justice. She could never believe that what happened to my family in Brisbane would be possible in a democracy.

“In a police state, yes.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout