Six little words: secrets die with a dirty cop

Terry Lewis died without admitting to any of the corruption that he had lied about for so long - except for one sunny afternoon in my kitchen.

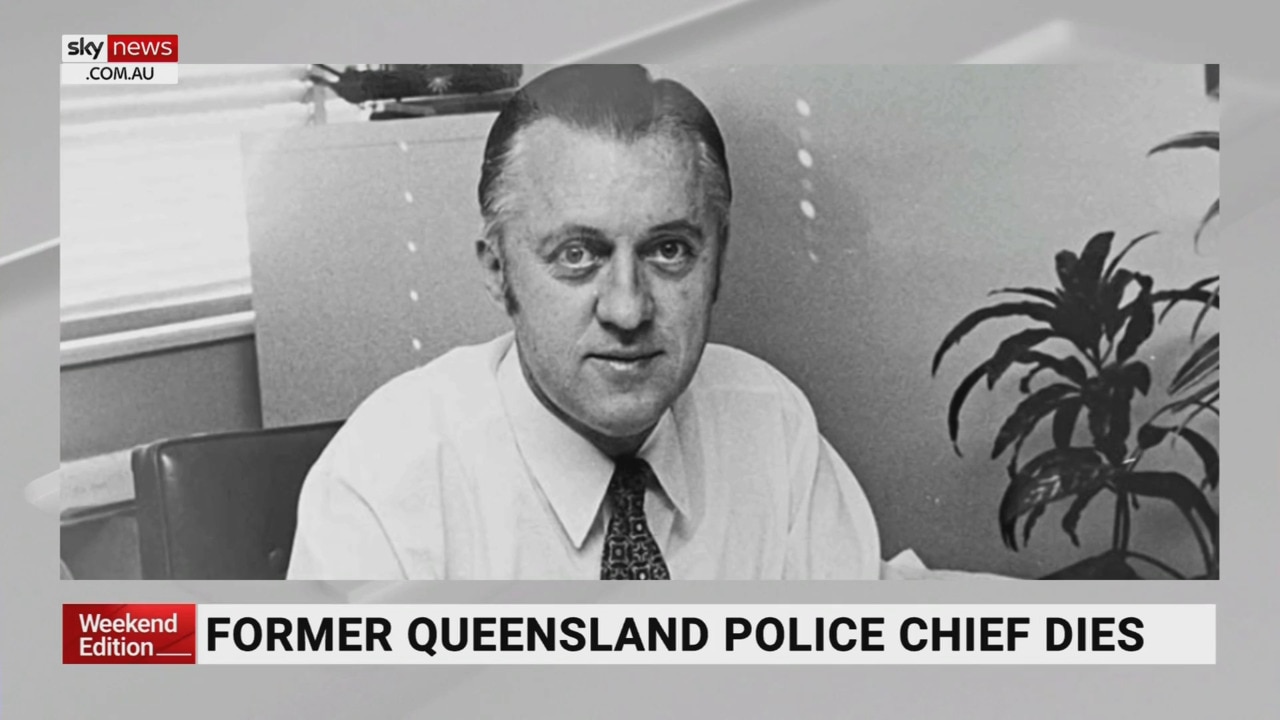

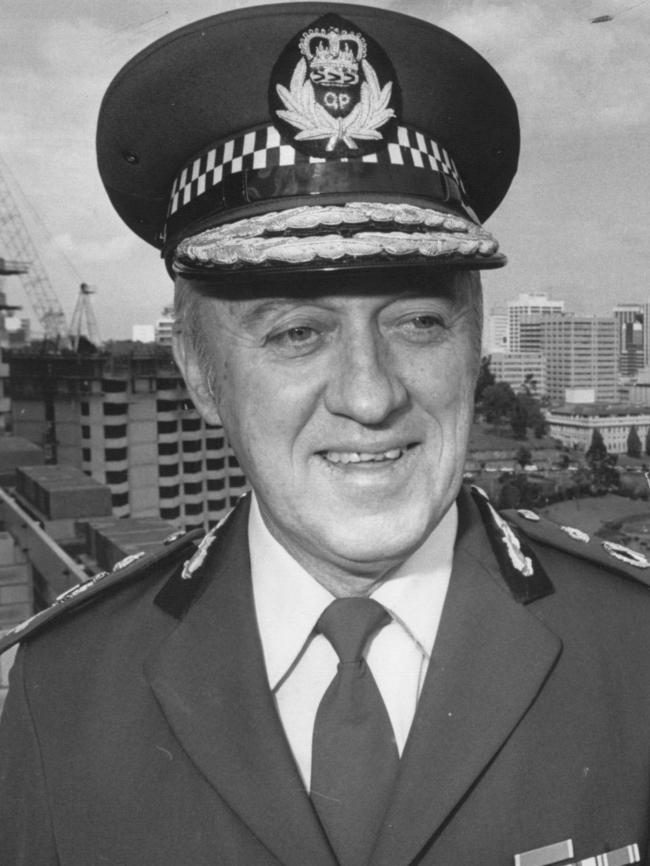

One warm Sunday in December 2010, I invited former Queensland police commissioner, former knight of the realm and convicted felon, Terry Lewis, to my home in inner western Brisbane for a barbecue lunch.

For much of the year I’d been interviewing Lewis for a book on his life and times. We both didn’t know then that the interviews would extend for another two years, and result in a trilogy of books not just about Lewis but about Queensland police and political corruption during the second half of the 20th century.

Lewis would completely sever ties with me on the publication of Jacks and Jokers.

But that was well into the future, and on this summer Sunday Lewis, then a spritely 82, knocked on the door right on time, bearing a bottle of wine in a paper gift sleeve.

Lewis met for the first time my wife Kate, and two small children. He was, as always, impeccably mannered. His checked short-sleeved shirt was so thoroughly ironed that the sharp pleats on the sleeves angled outwards like small wings.

I had the steaks on the barbie on the back deck and excused myself, leaving him in the kitchen with my wife. I could see them through the window, happily nattering away.

After lunch, and as Lewis prepared to leave, we made arrangements for our next interview at his home, and said our goodbyes.

Then Kate, a psychologist, closed the front door, turned to me and said: “Oh. My. God. You won’t believe what he told me in the kitchen before we ate.”

“What?”

“He said, ‘We were all on the take’.”

Six words. Six words I would spend years trying to get out of Lewis, and never manage to. Six words that were never prised out of him during two years of the Fitzgerald Inquiry into police corruption, nor during Lewis’s subsequent trial and conviction on charges of corruption.

Six words that dropped unexpectedly like a teaspoon on that kitchen floor in Brisbane’s inner west on a Sunday afternoon, to a person he had only just met. Six words that, as far as I knew, never crossed Lewis’s lips again, right up to his death last Friday afternoon.

In late 2009 an acquaintance of Lewis’s phoned and told me the former commissioner was finally interested in “telling his story”. Would I meet with him?

What was he like now, I asked, as an old man?

“You can still see the hint of the rat’s gold tooth,” the acquaintance told me.

Out of curiosity I turned up at Lewis’s house in Stafford Heights in Brisbane’s inner north and we talked. That meeting turned into our lengthy string of interviews – over 70 hours of audio and 370,000 words of transcript over three years.

I was under no illusion that Lewis would tell the truth about his controversial police career.

Incredibly, he had always maintained his innocence, despite the findings of the Fitzgerald Inquiry. In the aftermath, Lewis was charged with 15 counts of corruption, along with perjury and forgery. In 1991 he was convicted and sentenced to 14 years in jail, serving seven years.

A life of lies

In person, Lewis was genial, often humorous, seemed to possess an almost photographic memory, even in his early 80s, and seemed incredulous that all these bad things had happened to him.

According to Lewis, he had been (ask many of the men who worked under him) a good and thorough commissioner and had done great things for the state of Queensland, before his life and career inexplicably came crashing down.

Not an interview went by when he didn’t call out his primary enemies, namely commissioner Tony Fitzgerald, of course, but others too, including former deputy premier Bill Gunn, who had established the 1987 inquiry, and former premier Mike Ahern, who took over when Joh Bjelke-Petersen was ousted in December 1987, near the start of the inquiry.

There were fellow police, too, purely motivated by jealousy.

What I didn’t expect was that Lewis lied to me within 20 minutes of our first interview on February 1, 2010. He told me the story of his mother, Mona, who had walked out on him and her husband, Lewis’s father George, a good and honest railway storeman in Ipswich, for the bright lights of the Brisbane horse racing scene. She was a hopeless punter, he told me.

Lewis said he left school, aged 12, and caught the train to Brisbane on his own – Horatio Alger style – to find the wayward Mona. Never once, he said, did his mother tell him she loved him.

It was a hardluck story. But it wasn’t true. Court documents revealed George was, in fact, a chronic drunk, and had beaten Mona so badly that in one instance of violence she lost an eye. They were divorced in the 1940s.

I asked myself over and over: Why would Lewis recast, of all things, his foundation story?

I reasoned that if he was prepared to lie about that, then I had to be ready for weeks, months and, in the end, years of mistruths. During those regular meetings, I saw many different Terry Lewises.

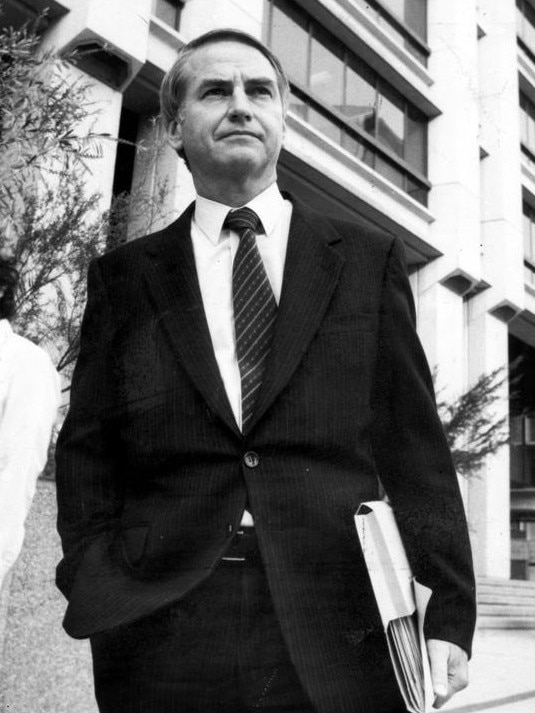

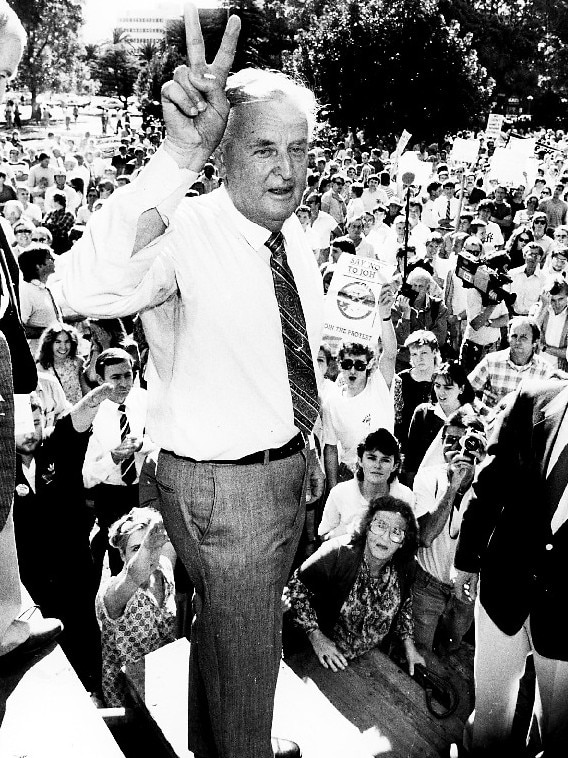

I witnessed his struggle with prostate cancer. Family ructions that saw him move house, from Stafford Heights to a small townhouse just off the road to a rubbish dump in Brisbane’s northwest. His excitement at regular lunch meetings with some of his old police mates on the Gold Coast, including John Meskell and Pat Glancy. Once, the former Director of Prosecutions, Des Sturgess, joined them for drinks. I listened to his ceaseless frustrations that the Fitzgerald Inquiry was set up to destroy him. That fellow officers had lied to get back at him for sleights that went back to the 1950s, when Lewis was a young constable on the streets of Brisbane, teaming up with detectives Tony Murphy and Glen Hallahan. The trio became known as the Rat Pack. Lewis said he could never understand the term. Did it have something to do with Frank Sinatra?

On occasions when I challenged his version of events, the scrapper from working-class Ipswich emerged. Lewis would lash out. He expected me to simply dictate his story and shape it into a book.

No responsibility

It was during these testing times I managed to glimpse, as I had been warned, the rat’s gold tooth.

On one rare day he appeared at the door in tracksuit pants and a shirt, unshaven and with messy hair. He wasn’t feeling well. We were taking too long with the book project. He was feeling flat about how his life had turned out and thinking everything would have been a lot easier if he had “never been born”.

He said while he was in jail he contemplated taking his own life. All because of the Fitzgerald commission of inquiry.

And this was the thing about Lewis. A life that had culminated in being crowned the top law enforcement officer in Queensland, the bestowing of a knighthood and other honours, the construction of a modest mansion in the Brisbane suburb of Bardon, and the promise in retirement from Bjelke-Petersen of a possible trade commissionership in London or Los Angeles had evaporated because of the perfect storm of a myriad Machiavellian forces.

The media, the inquiry, self-interested politicians, jealous police, crooks with a grudge, perjurers saving their own skin, corrupt cops clutching for indemnities – all of these, and more, set out to destroy Terry Lewis. Never once in our time together did Lewis take responsibility for his actions, accept blame, come clean on three decades of nefarious deeds, or own up to corruption.

Never once did he acknowledge his corruption apprenticeship that began in the 1950s when he was extorting money out of sex workers on the streets of Brisbane, his work as a bagman for police commissioner Frank Bischof, his efforts to intimidate and destroy the credibility of witnesses before the National Hotel Inquiry in 1963-64, his relentless attempts to undermine honest commissioner Ray Whitrod, his pivotal role in providing Bjelke-Petersen, via his police troops, with a 24/7 private army to be used as desired, his deliberate destruction of the careers of hundreds of promising police men and women who rejected offers to join the corrupt system known as The Joke, or who stood up against it.

Our relationship ended on the publication of Jacks and Jokers in early 2014. I had somehow gone off reservation, wildly misunderstood his brief and his literal instructions, and was now a lost cause. The request for the return of all research documents, the property of Terry Lewis, came through one of his daughters, not the man himself.

I never spoke to him again.

Over the years, even after the publication of the trilogy, I became the accidental lightning rod for stories about Lewis. Hundreds of people phoned and emailed me with sordid tales, details of brown-paper bags of cash being slipped into a crack in the wall of the Lewis home in Bardon. Of a secret room-sized vault that contained Lewis’s gun collection – the most extensive in Australia. One woman wrote: “I hated it when Hazel Lewis came into my shop. When she bought something she paid for it with these old, musty bank notes she pulled out of her purse. They smelt like they’d been buried.”

I also heard contemporaneous stories about Lewis. He had gone to live in a granny flat with his daughter in Ashgrove. He was seen at a barber shop getting a haircut, “looking old”. He had advanced dementia and been moved into a hospital ward. Then last Wednesday – Lewis was gravely ill.

And finally, last Friday night, as I sat with my two oldest children – both of whom had met Lewis at that lunch all those years ago and had called him “Mr Lewis” – in the nosebleed stands at Suncorp for the Broncos’ match in Magic Round, a call came through. Lewis was dead.

Power and greed

As I sat surrounded by 50,000 screaming football fans, I thought of the Petrie Terrace police barracks, just up the road, where Lewis had trained as a cadet in the late 1940s.

It was the start of a career that would end in total infamy.

Let’s make no mistake here. Lewis was a central figure in one of the most vile and all-encompassing systems of corruption that infected almost every crevice of Queensland life. People lost their lives. Lewis was a disgrace to the oath he swore to keep. He let down himself, his family, his profession, his community and his state.

And it was all about just two things – power and greed.

We were all on the take, he quietly told my wife in that small kitchen all those years ago. A concession, I think now, to perhaps his only Achilles’ heel – educated women.

Sitting watching the football at Suncorp, I also remembered something my grandmother told me when I was a teenager. She had lived just around the corner from the stadium, in Beck Street, Rosalie, and had been a near-neighbour of the Lewises for a while.

“Mud finds its own level.”

As the crowd launched into a Mexican wave, I thought of the stupendous rise and fall of Terry Lewis, from poverty in Ipswich, to Queensland police commissioner, to confidant of the powerful and the wealthy, to prison and finally to seeing out his days as a suburban pensioner.

Terence Murray Lewis, in the end, found his own level.

Matthew Condon is a senior reporter for The Australian and author of the Lewis trilogy – Three Crooked Kings, Jacks and Jokers and All Fall Down.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout