Bellino brothers’ vice grip on Brisbane

The death of Gerry Bellino soon after his elder sibling Tony and almost 50 years after the Whiskey Au Go Go fire closes an extraordinary chapter in Brisbane’s criminal history.

On another humid early autumn morning in Brisbane last Wednesday, workers in hard hats went about their business gutting a two-storey office building in Fortitude Valley, just north of the city centre.

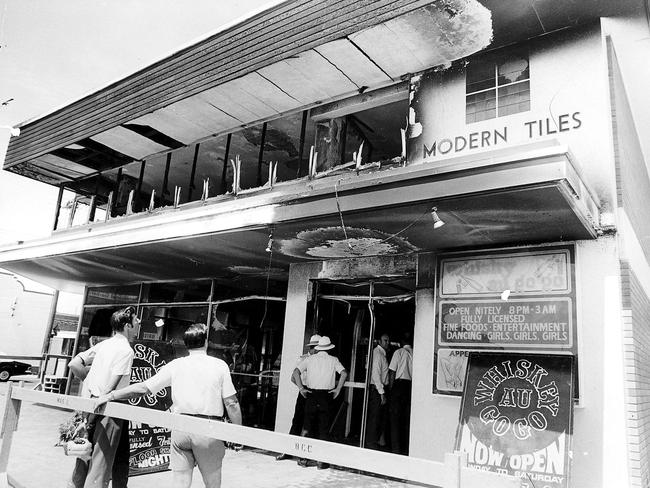

The building, on the corner of St Pauls Terrace and Amelia Street, had been there for decades and had had many incarnations – a floor tiling outlet, office space, a gym.

Upstairs, the workers had stripped the floor to bare concrete, and old electrical wires dangled from the ceiling like forest vines. It would soon be transformed into a medical centre.

But nothing could erase this building’s notoriety.

In 1973, the upstairs level operated as the Whiskey Au Go Go nightclub, and in the early hours of March 8 that year 15 innocent lives were lost when the club was firebombed.

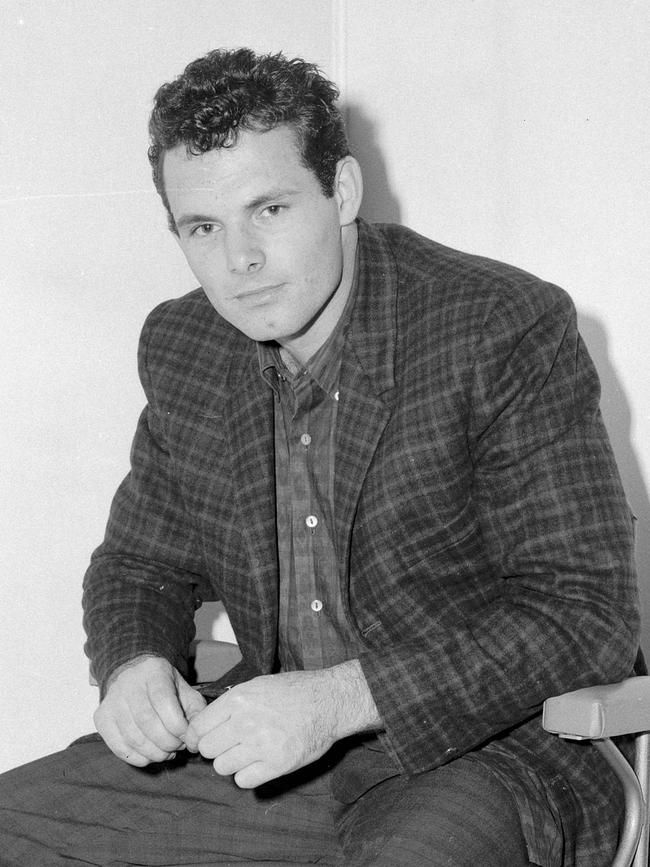

Two gangsters – John Andrew Stuart and James Finch – were arrested, charged and ultimately convicted of that mass murder, but subsequent inquests have failed to answer what really happened at the Whiskey that night, why it occurred, and who else might have been behind the attack.

On Wednesday, those demolition workers stood at the upstairs window (where the club’s front bar used to be, and where deadly smoke poured up the stairwell) and watched a sombre and moving ceremony unfold down below in Amelia Street – the gathering of survivors of the fire, victims’ families, police, fire brigade and ambulance officials, and local politicians – marking the 50th anniversary of that terrible night.

Some of those hard-hatted workers weren’t born when the tragedy occurred, and they couldn’t have known that they were toiling away in a space where some of the club’s young bar staff and kitchen hands, and a cross-section of the public, from musicians to soldiers to farmers, had perished half a century before.

In a serendipitous moment last Wednesday, Brisbane newspaper The Courier-Mail published a humble funeral notice for one BELLINO, Gerardo, 80.

This, and the Whiskey memorial, were sure signs that an extraordinary era in Brisbane’s criminal history had come to a close. As George Harrison so eloquently put it, all things must pass.

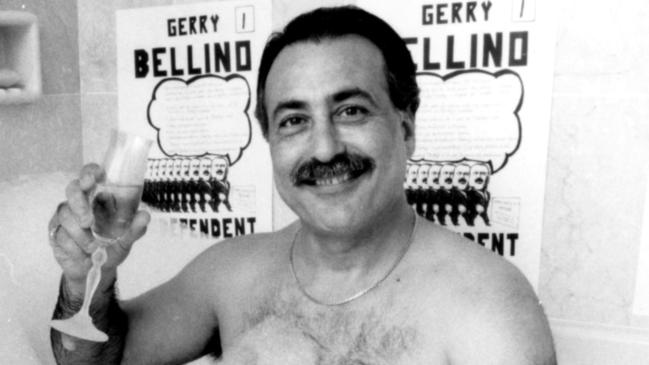

Gerardo “Gerry” Bellino – who died on March 1, having been diagnosed with prostate cancer some years ago – was a seminal figure in Queensland’s criminal history in the late 20th century. In 1987 he was named, along with brother Tony, in the epochal Fitzgerald Inquiry into police and political corruption’s terms of reference, and was later jailed for corruptly paying police.

He was top dog in Brisbane’s so-called underworld in the 1970s and into the ’80s.

And while in reality he was more a local Salvatore “Big Pussy” Bonpensiero to Sydney and Melbourne’s Tony Soprano, he rose from humble post-war Italian migrant beginnings to running a multimillion-dollar vice empire that included prostitution and illegal gaming.

At its peak, prior to the Fitzgerald Inquiry (which ran from 1987 to 1989), Bellino’s consortium was supposedly paying corrupt police $17,000 to $20,000 per month to continue business unhindered and free of prosecution.

The empire’s turnover was in excess of $1m a year, based on income from four illegal casinos, up to nine brothels and several escort agencies across Brisbane and the Gold Coast.

At 142 Wickham Street, Fortitude Valley, Bellino ran a successful illegal casino that entertained everyone from politicians to celebrities to journalists. It was the casino former police minister Russ Hinze, during the reign of Joh Bjelke-Petersen, claimed didn’t exist. (Although many witnesses through the decades have sworn that Hinze was one of the casino’s most popular customers.)

Directly beneath the casino was a massage parlour, Bubbles Bathhouse. And beneath that, the Bellino consortium’s HQ, where the empire’s money was counted and divvied up.

Gerry Bellino was a dichotomous figure. He was a one-time adagio dancer (an acrobatic, circus-style movement involving balancing a dance partner in midair). He was also a songwriter. In 1963, before a life of vice began, he lodged official copyright over an original musical – Sharon, Oh Sharon.

He was reputedly the most powerful and ferocious bareknuckle fighter in Brisbane. Nobody came away unscathed from a tangle with Bellino.

And yet many of the sex workers employed by him attested that he was a fair and reasonable boss, and never violent.

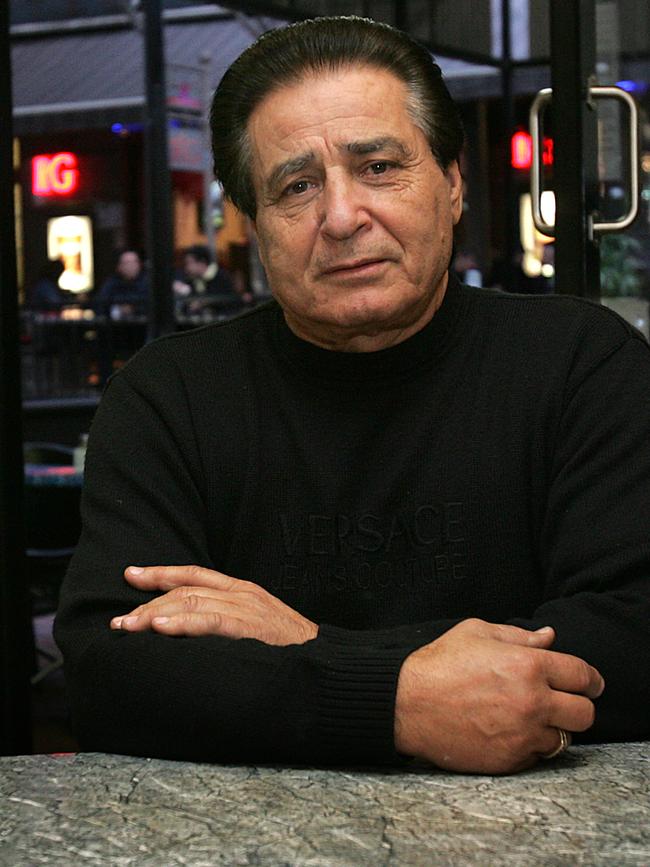

His older brother, Tony – himself forever entangled in an adagio-style dance with Gerry as to whether he was his younger sibling’s business partner in vice – always claimed he was never involved in the illegal gaming and massage parlour scene, just a businessman who looked after the Bellino family’s various nightclub and restaurant interests. (Although he did seem to share his younger brother’s musical bent – in 1987 he released a solo album, Shame and Scandal in the Family.)

Tony, 82, died in Brisbane in late September last year, several months after he appeared as a witness at the revived inquest into the Whiskey Au Go Go mass murder. Queensland Coroner Terry Ryan’s final report into the Whiskey is expected later this year. Cocky, loud and seemingly in rude health, Tony told the inquest in February last year that when he ran his spaghetti restaurant and Pinocchio’s nightclub in the Valley in the early 1970s, he refused to pay protection money to one of Queensland’s most notorious corrupt detectives and a member of the so-called Rat Pack of bent officers – Glendon Patrick Hallahan. As a result, Tony claimed, fights were regularly started at the club to disrupt business.

When questioned at the inquest about his past, Tony stated: “I’m not a mafia man. I’m just a businessman.”

Photographed outside the Brisbane Magistrates Court building after giving his evidence, he appeared younger than his years. He looked trim, his hair pitch black and swept back off the forehead, Al Pacino-style, his face adorned with a pair of dark Ray-Bans. He appeared every bit the smooth mafia operator he claimed he never was. Tony spoke exclusively to The Weekend Australian not long before his death. He recalled – in his broken Italian-English – those wild times in Brisbane in the 1970s with brother Gerry.

He said he loved his brother, but they were not on speaking terms.

He remembered when Gerry was having difficulty getting a liquor licence for his World By Night strip club.

“My brother Gerry didn’t like work,” he said. “It doesn’t matter. He is my brother.

“But he said he couldn’t get a licence because upstairs (at the club) they opened up a bloody brothel. So they couldn’t get a licence. What an idiot.”

Tony went to Sydney in the 1960s to study nightclubs and see what was on offer on the Kings Cross strip, and came back to Brisbane and set up his first restaurant and nightclub.

He liked the vibrancy of the Sydney clubs. He liked the strippers. Four of them left the Emerald City and started working for him in Brisbane.

“A funny thing happened,” Tony said. “I was a plasterer, did all my apprenticeship and everything. I was one of the best plasterers in Australia.

“But I opened up a restaurant in the Valley. A spaghetti bar. Yes. Open 24 hours. And that’s when all that shit started.

“You know, the cops were sending people there because the person that had it before, he got shot in Sydney, he was a criminal. And that, you know, he was selling grog, and he was paying the coppers. Anyway, it’s a long story from then on because I’ve suffered.”

He said the entire Bellino family’s reputation had been destroyed by the Fitzgerald Inquiry.

In August 1991, Gerry, then 47, was sentenced to seven years in prison after being found guilty of four counts of official corruption. Gerry and his criminal partner, Vittorio Conte, were convicted of paying $966,000 in bribes to former Licensing Branch detective and bagman Jack Herbert between 1980 and 1987.

Justice John Kimmins recommended parole after two years.

Gerry would serve time at Brisbane’s Wacol prison, a temporary home he would ultimately share with corrupt former police commissioner Terence Murray Lewis, who was found guilty of official corruption and jailed for 10 years in the fallout from the Fitzgerald Inquiry.

Gerry denied that he was corrupt. “I might bend the law but I don’t break it,” he once reportedly said.

This was at odds with one of the Fitzgerald Inquiry’s chief witnesses, Katherine James, who worked on and off for the Bellinos through the 1970s and ’80s. She said she was employed as a card dealer for Gerry at the illegal gambling casino above Pinocchio’s.

In her official statement, James said: “I was a dealer in the manilla game and got $100 a night plus tips. The game would start at about 11 o’clock at night and shut down at about six in the morning.

“I was hired as a dealer by Gerry Bellino. Tony mainly looked after the night club downstairs and Gerry would look after the gambling.”

Her evidence also flew in the face of Tony’s assertions, right up to the last, that he had nothing to do with Gerry’s vice operations. “Tony Bellino was there every night,” she told the inquiry. “The role which Tony would play upstairs would be to take care of the money and organise sufficient staff for upstairs and sufficient drink and food waitresses.”

James said of another illegal Bellino casino she worked at in Brisbane: “Gerry and Tony Bellino would come there at least once a week to collect the money.”

Tony, in the final months of his life, still smarted at the impact of the inquiry.

He said: “I don’t understand. I’ve done nothing wrong. I’ve helped people. I’ve lent a lot of money out to people … that didn’t have no money. I … had to do something, you know.

“And you know what? When I was in trouble, nobody came around. They’d completely … this Fitzgerald (Inquiry) destroyed my life. They don’t care about that do they? And my kids know that.

“You don’t know me too well. If I have a friend, I have a friend. If I don’t have a friend, they can all go and get stuffed. I cancel all my friends. Because when I needed help after Fitzgerald, all the properties I had, all the money I had, I couldn’t even buy a cup of coffee.

“I was back to the way I was when I was in Sicily as a four-year-old. So you can imagine how I felt (at) the time … My wife was crying. My kids … some of them turned out to be a little bit bad because of what happened because I had everything. They had nothing. You know what I mean?”

As recently as 2019 Tony Bellino sued The Courier-Mail for defamation over a small article that called him a “prominent casino and brothel operator”.

At a hearing in the Federal Court before Justice Geoffrey Flick, Tony argued he was not a part of any seedy criminal underbelly, but – again – just a nightclub owner.

He lost the case.

Justice Flick’s judgment included robust testimony from Bellino, denying he was some arch gangster.

“This is disgusting, telling me that I’m a criminal,” the testimony reportedly said. “My father was an honest man and I am an honest man.

“The Bellino family in Italy, if you see, they were composers, they were merchants, they were always doctors and God knows what, but I never, ever would have done anything to destroy my father’s name.”

The Bellino brothers, who may have been described in a quainter era as “colourful identities”, with their stories of Wild West-style brawls in their restaurants and clubs, gangsters with guns showing up to settle scores, dirty cops and rivers of cash, are gone. Now the literal face of the tragic Whiskey Au Go Go nightclub is being erased.

And all things must pass.

Former Queensland police undercover operative and whistleblower Jim Slade was a young officer in the early 1980s when a senior officer offered him a fortnightly cash bribe to join the corrupt police system known as The Joke.

The officer told Slade the windfall was courtesy of “Uncle Gerry”.

Slade declined.

“It’s the end of an era,” Slade said on Sunday.

“What an incredible relationship those guys (the Bellinos) had with the police back in the day, with politicians – to know that if they made friends with those people they’d be set for the rest of their lives.

“The depth of their criminality may never be proved. I don’t think we’ll ever know the full story. But that’s a whole chunk of my life gone, with the passing of the Bellino boys.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout