Out of luck, out of friends, out of time: fitting end to Roger Rogerson’s disgraceful life

I was writing an article on cops in jail. By then, Rogerson had served more than five years in prison for perverting the course of justice, not once but twice.

I asked Rogerson what those first few days behind bars were like. The fall from grace, the public exposure, the private ruin, not to mention that some of his fellow inmates who Rogerson might have verballed into long prison sentences might not be all that pleased to see him.

His answer was odd. He battled to articulate any emotional response. The call finished with him inviting me out for a drink which I politely declined.

In truth, Rogerson was a celebrity in prison. His first stretch of 3½ years was spent mainly at HM Berrima, a 19th-century slammer that he shared with a hundred or so villains, including 17 other police officers, swept up in royal commissions various.

And while on remand awaiting trial for the murder of the 20-year-old wannabe gangster, Jamie Gao, Rogerson was a rock star, signing autographs to young crooks in the remand section at HM Silverwater.

Rogerson experienced no particular hardship in jail, save perhaps for his final days where he was known to have had at least one serious fall.

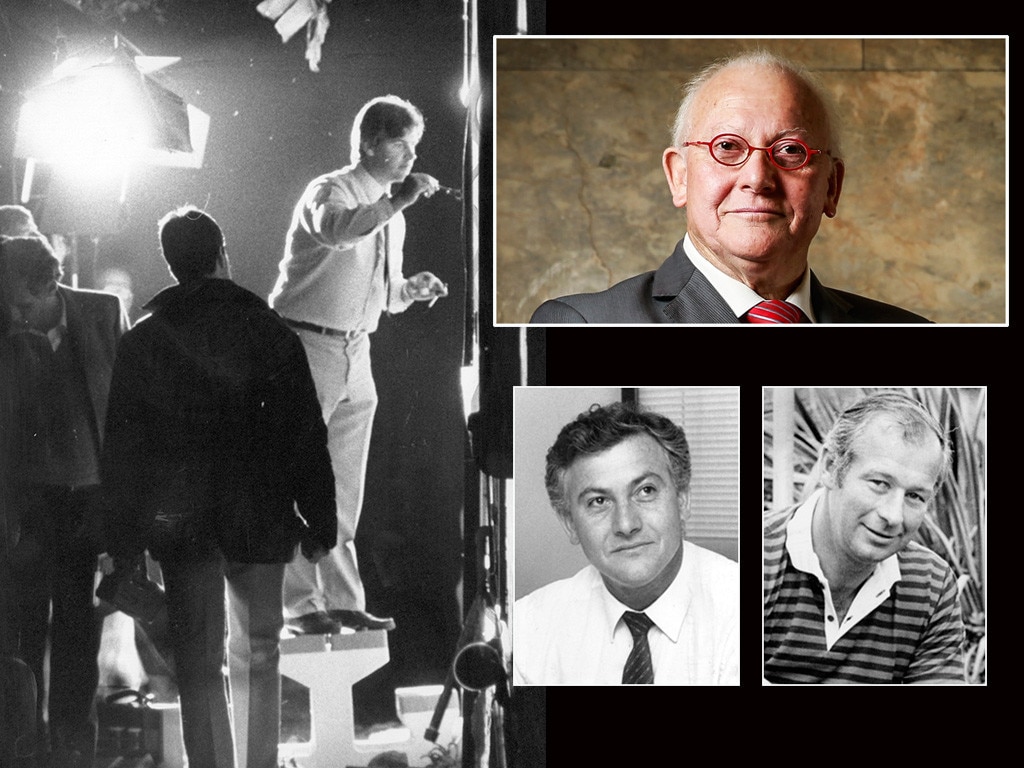

I interviewed Rogerson five times and had a chat with him over a few beers on a couple of occasions. His performance in the interviews was always measured, his lines rehearsed, and deflections prepared in advance. He gave nothing away.

Away from the cameras and over a beer, he was charming and funny, as psychopaths often are. He told his old amusing cop anecdotes and we all laughed. Another journalist asked Rogerson, perhaps mischievously, if he had heard from a certain senior copper who was one of the first to investigate Rogerson and ultimately led to his removal from the force and his first criminal charges.

Rogerson’s reply was unprintable and it stood as a mask slipped moment. His words hung in the air for a second and I realised at once that Rogerson was a very dangerous man. Rogerson sensed my unease and turned back to his cabaret routine.

“Never plead guilty,” Rogerson pronounced loudly, an aphorism he may as well have had tattooed on his forehead. He never did. He pleaded not guilty to perverting the course of justice in 1990 and then again for the same offence in 2005. Juries disagreed.

He pleaded not guilty to offering Mick Drury a $40,000 bribe and was acquitted. He pleaded not guilty to conspiracy to murder Mick Drury at Drury’s home on June 6, 1984. Drury was shot twice in the chest through his kitchen window and was lucky to survive his injuries. At trial, the jury never got to hear the evidence of Rogerson’s bribery attempt as it was deemed inadmissable.

For the record, his co-conspirator Melbourne Painter and Docker and drug dealer Alan Williams pleaded guilty to conspiring to murder Drury with Christopher Dale Flannery and Roger Caleb Rogerson. Williams received a 10-year jail sentence. Rogerson walked.

Rogerson pleaded not guilty to the murder of Gao. Rogerson’s co-accused, Glen McNamara adopted Rogerson’s creed and pleaded not guilty, too. Gao was killed with two shots in the chest. Two shots again. A sign, perhaps, of police weapons training. But McNamara was an ex-copper, too.

We will never know with any certainty who fired those two shots. McNamara and Rogerson blamed each other. In the end it didn’t matter. Rogerson and McNamara were engaged in a joint criminal enterprise to kill Gao and steal almost 3kg of ice Gao had himself pinched from Chinese crime gangs. The ice was worth $700,000 at wholesale prices at the time. The Chinese gangs didn’t make any effort to recover their losses. Funny that.

Both Rogerson and McNamara went down, sentenced to life in prison.

Rogerson killed three men in the line of duty. Bank robber Phillip Western in 1976, another counter jumper, “Butchy” Burns in 1977, and drug dealer Warren Lanfranchi in 1981.

When Burns was killed as he and two associates prepared to alight from their car to stick up a bank, Rogerson and another senior detective who had both pumped shotgun fire into the car, screamed at each other over who had fired the fatal shot. “I shot him.” No, I did.” The blue was over who would receive police commendations.

Rogerson killed opportunistically. He killed for medals. He killed because he enjoyed it. He also killed for money. In a can’t-see-the-forest-for-the-trees moment, no one has ever bothered to ask why Rogerson was so close to the hit man Chris “Rentakill” Flannery. A long look at a range of unsolved underworld murders for which Flannery is the presumed culprit points to Rogerson running a murder for hire business with Flannery possibly playing the roles of executioner and/or unwitting dupe.

Flannery went missing in May 1985 and is presumed murdered. His body has never been found.

I asked Rogerson’s biographer and the man who knows more about the life and crimes of Rogerson than any other, former NSW detective turned author, Duncan McNab about the murder-for-hire business. It is speculation on my part but McNab believed it could easily be true.

In his 60s and limping heavily after a fall from a neighbour’s shed, Rogerson was in contact with Melbourne heavies, offering his services as a gun for hire in the city’s underworld war around the turn of the century. The gangsters replied with incredulity, believing his age and infirmity would discount him as a hit man. “I can still shoot straight,” Rogerson told them. There is no evidence that they took him up on his offer.

Rogerson’s life ended in the Prince of Wales Hospital on Sunday, January 21, transferred with no sign of brain activity from Long Bay Correctional Complex. We might quibble on the technicalities but he effectively died in jail. It was a fitting end to a disgraceful life. Out of luck, out of friends, out of time.

The lesson on the death of this prodigious criminal and stone killer is that crime does not pay. Plus you can save a few bob on the catering at the funeral.

The last time I spoke to Roger Rogerson was 12 years ago. Mark Standen, a NSW cop who had reached the lofty heights of assistant director at the state’s crime commission had been sentenced to 22 years in prison for his role in trafficking 300kg of pseudoephedrine, a methamphetamine precursor drug.