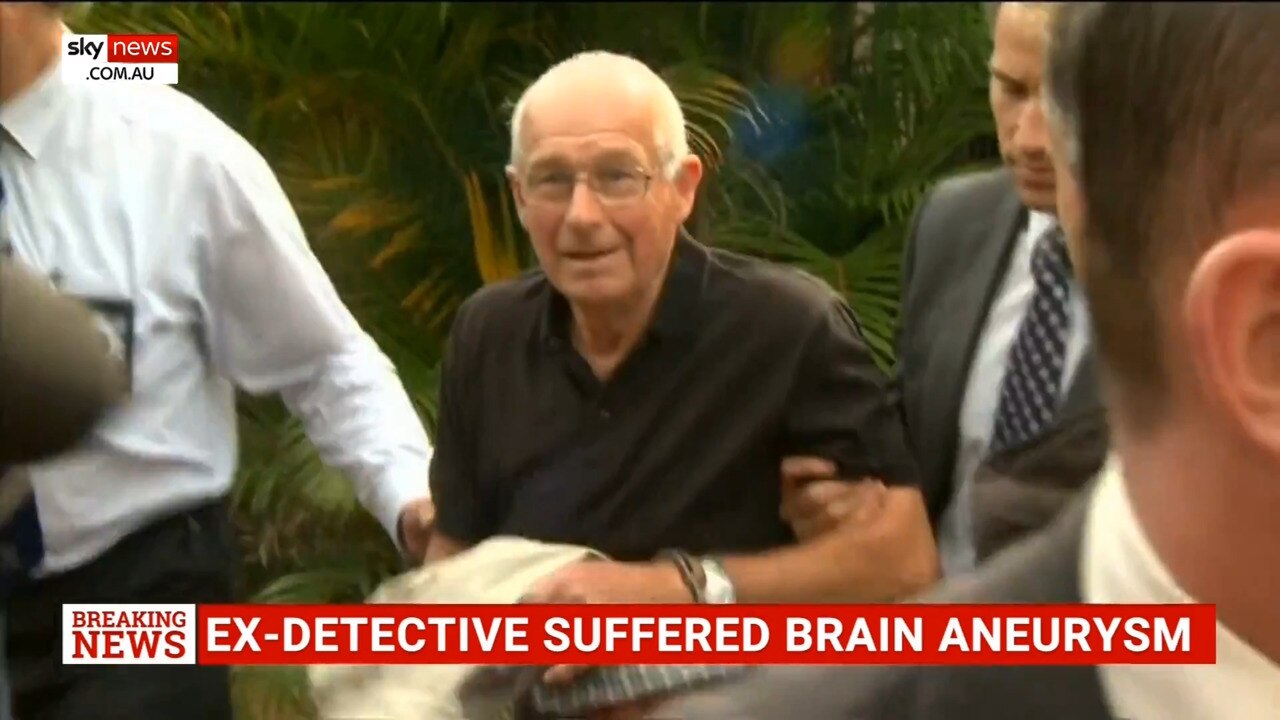

Corrupt cop Roger Rogerson will take the secrets of at least three cold case murders to his grave

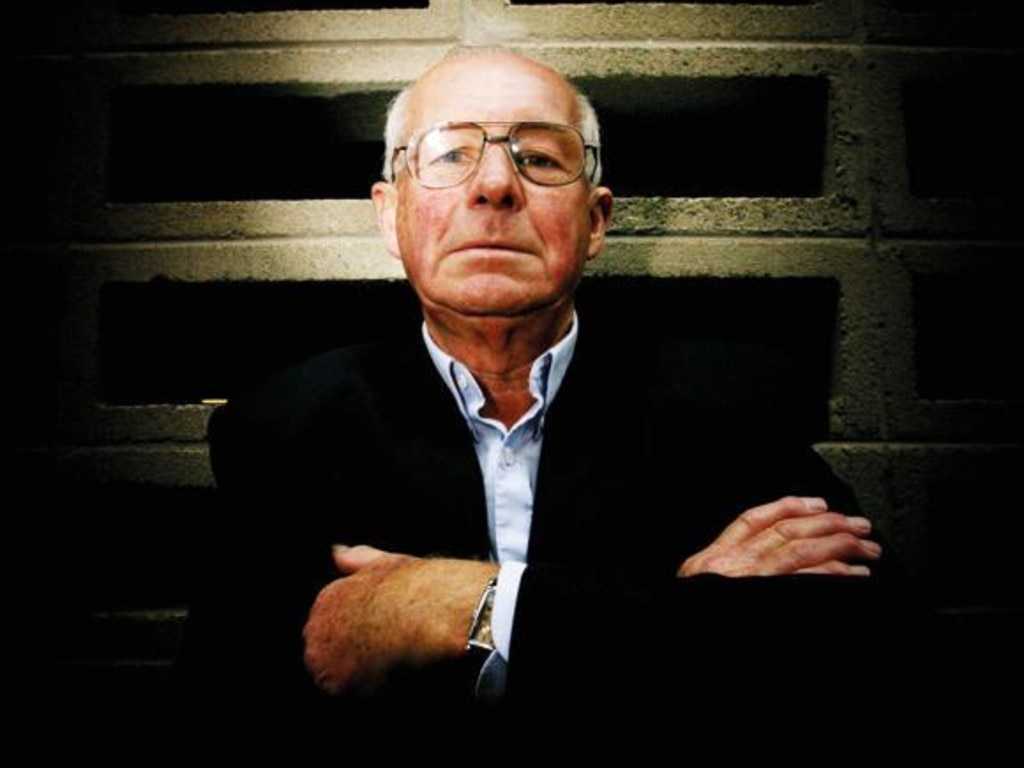

Roger Rogerson knew the hardest crooks and the mechanics of Sydney’s underbelly, and advantageously he knew how police and the law worked.

Given the complicated passage of his life, and the perhaps unfathomable workings of his mind, the passing of Roger Caleb Rogerson leaves in its wake more prickly questions than answers.

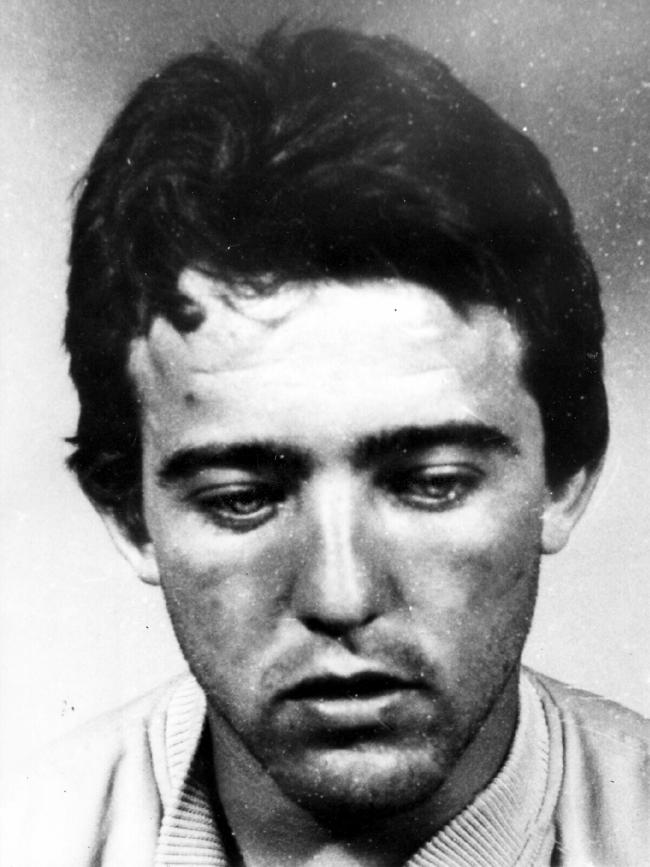

He was an enigma – a brilliant young detective who joined the NSW police force in 1957, rose to the Special Weapons and Operations Squad in 1967, and by 1973 was already the golden boy on a trajectory towards the commissionership when he entered the Armed Hold-Up Squad.

Then something happened. By the 1970s Rogerson – largely left unsupervised by his superiors because of his stellar reputation – put aside his prowess as a meticulous investigator and seemingly applied his policing knowledge to facilitate a parallel career in crime.

He knew the hardest crooks and the mechanics of Sydney’s underbelly and, advantageously, he knew how police and the law worked. In Greek mythology, he would have been a perverse combination of Themis, goddess of law, order and justice, and Hades, the king of the underworld.

One thing is certain. From the earliest years of his career, Rogerson’s constant companion, apart from his service revolver, was death.

Policing and death are no strangers, but in Rogerson’s case death permeated his working life from the mid-1970s – coinciding with his work with the Armed Hold-Up Squad – and never ceased, even in retirement.

In 1976, for example, he was present at Avoca Beach on the NSW Central Coast when police fatally shot bank robber Phillip Western. Western was wanted in connection with the murder of a bank manager in Parramatta, and was on bail at the time he was shot dead.

In early 1978, after a tip-off, Rogerson and other members of his squad shot dead criminal Lawrence “Butchy” Byrne as he attempted to rob the South Sydney Junior Leagues Club of its Saturday night takings.

Byrne was struck in the head multiple times. Rogerson took the credit. An inquiry ordered by then NSW premier Neville Wran focused on tightening bail for dangerous criminals.

In August 1979 Rogerson was reportedly present when drug addict and bank robber Gordon Thomas was gunned down by police in Sydney’s Rose Bay.

There are numerous ways to look at this phenomenon, that Rogerson and death went hand in hand.

The 1970s were criminally volatile, not just in NSW, and his actions could be seen as the definition of effective policing. But this pattern – if that’s what it was in Rogerson’s case – continued.

It would be tempting for some, in the wake of Rogerson’s demise, to pin a raft of killings on him, to fashion a bogeyman and fit him with crimes that came even remotely within his orbit.

But there are three deaths involving Rogerson that have never been satisfactorily resolved. Crime writer and biographer Duncan McNab describes them as the Dodger’s “holy trinity”.

The first was the murder of drug dealer Warren Charles Lanfranchi on Sunday, June 27, 1981. The previous month Lanfranchi had ripped off a heroin dealer who worked for criminal Neddy Smith and Rogerson.

Lanfranchi ‘meeting’

Realising he was in grave danger, Lanfranchi contacted Smith to make reparations by way of a part-payment for the stolen heroin. And a meeting was arranged with Rogerson in Dangar Place, Chippendale, where Lanfranchi would apologise to Rogerson and smooth things over.

By the time Lanfranchi arrived there were 18 NSW police stationed in and around the meeting place, including Rogerson, who proceeded to shoot Lanfranchi twice – in the neck and into his heart.

Rogerson claimed Lanfranchi was armed and about to fire upon him. Lanfranchi’s partner, Sallie-Anne Huckstepp, claimed he went to the meeting unarmed. (Huckstepp herself, who never resiled from the fact that Rogerson had cold-bloodedly murdered Lanfranchi and was heavily involved in the drug trade – would ultimately be strangled to death by Rogerson’s criminal partner, Neddy Smith in 1986.)

A coroner found that Rogerson had killed Lanfranchi while “endeavouring to effect an arrest”.

The murder, in full view of his police colleagues, was a psychotically bold move from Rogerson, elevating him into the ranks of a police officer who would not hesitate to kill. It was both a warning and personal myth-making rolled into one.

Woodward silenced

The second case was the disappearance, and presumed murder, of Lyn Woodward, 24, who was embarking on a modelling career in Sydney in the early 1980s.

According to reports by crime writer Mark Morri, Woodward had dated drug addict Stephen Pauley, who introduced her to Lanfranchi and his partner, Huckstepp.

Woodward and Huckstepp became friends. In late 1981 Woodward gave evidence at the Glebe Coroner’s Court in relation to Lanfranchi’s shooting. She disappeared after leaving the court.

Twenty years later, at an inquest into her death, Neddy Smith claimed he saw Rogerson kill Woodward. She was prepared to give evidence – according to statements she made – that not only was Rogerson a major heroin dealer, but that some members of the Armed Hold-Up Squad actually planned bank robberies and shared the profits.

Rogerson was never charged with her death. It remains a cold case.

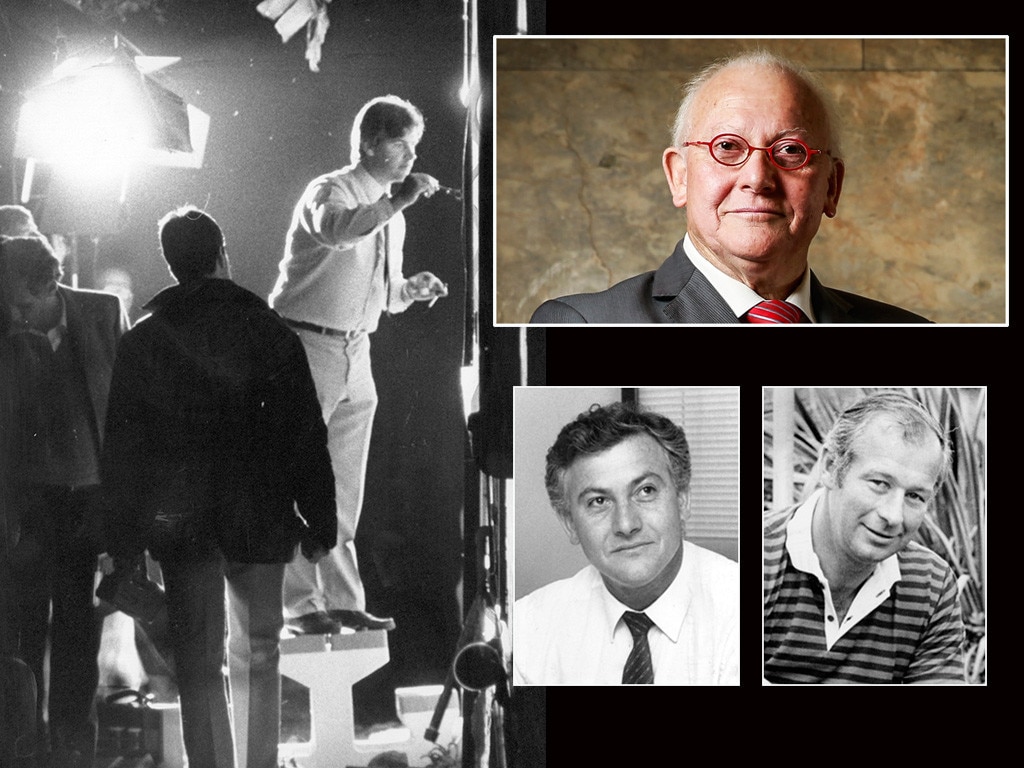

The third of the “holy trinity” was the disappearance and presumed murder of gangster Christopher Dale Flannery, aka Mr Rent-a-Kill.

‘Pest’ removed

By the time he was allegedly involved in the attempted murder of police officer Michael Drury in Sydney in 1984, Flannery had already been charged and acquitted of two murders.

Following the Drury shooting, organised by Rogerson because Drury refused a bribe to drop the case against a major Melbourne drug dealer, Flannery went about his business in Sydney until May 9, 1985, when he left his home in the Connaught building in the Sydney CBD to visit criminal heavy George Freeman. Flannery was on Freeman’s books as a debt collector.

Flannery was never seen again.

At the inquest in 1994 into Flannery’s death, an interview between his wife, Kathleen, and the then National Crime Authority in 1986 was tendered.

In the interview Kathleen supposedly said Rogerson had visited her two weeks after Flannery disappeared and offered her $50,000 to “shut her up”.

It was understood Flannery had been murdered not just for what he knew about the attempt to murder Michael Drury but, according to hearsay evidence, Rogerson believed Flannery had become “a pest”.

Flannery’s murder also remains a cold case.

When asked this week who she think murdered her husband, Kathleen Flannery told The Australian: “Roger.”

Some believe Rogerson’s death will seal off any chance of resolving these outstanding cases.

Others stress that the Dodger’s absence, however, should not impede the quest for the truth.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout