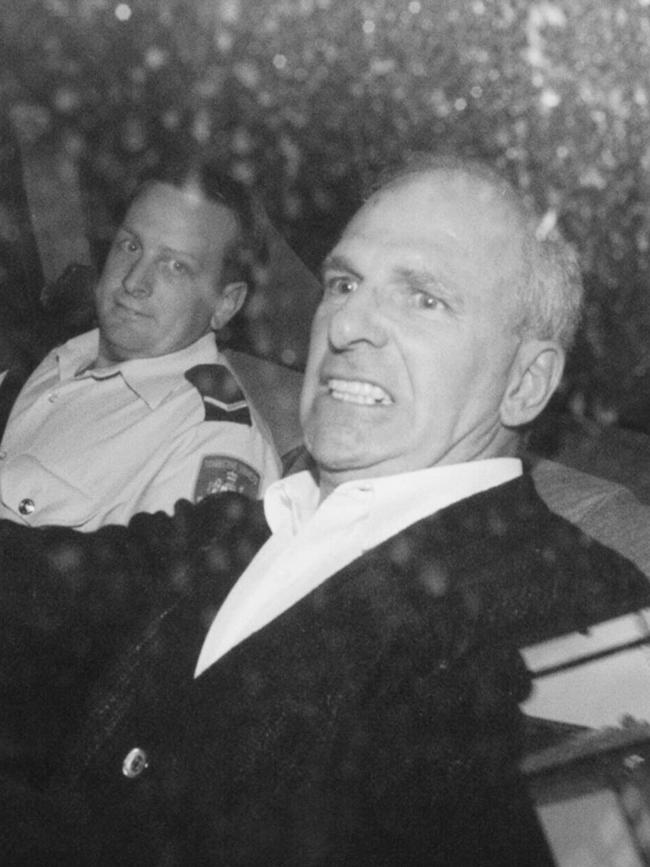

Roger Rogerson dead at 83: corrupt NSW cop forever associated with murder

The disgraced NSW cop will likely be better remembered for the murders he committed, and for others he organised, than for the ones he solved.

Like many a career detective, Roger “The Dodger” Rogerson’s name will forever be associated with murder. In Rogerson’s case, however, he will likely be better remembered for the murders he committed, and for others he organised, than for the ones he solved.

The disgraced former NSW detective – arguably the most infamous in a state with a colourful record on law enforcement – was serving a life sentence for the 2014 murder of a 20-year-old drug dealer when he was found unresponsive in his cell on Thursday night.

The one-time detective-turned-killer and drug dealer was taken to the Prince of Wales Hospital in Randwick, Sydney, just before midnight on Thursday following a suspected brain aneurysm.

The 83-year-old died at the hospital at 11pm on Sunday night after his life support was switched off about 11.30am on Friday.

Born on January 3, 1941, Roger Caleb Rogerson was 17 when he joined the NSW Police Cadets. Two years later he was sworn in as a Probationary Constable. After starting out as a uniformed constable at Bankstown, Rogerson was soon training as a detective. At a short-staffed Criminal Investigation Branch, he quickly made a name for himself as a murder investigator.

By the early 1970s, and with his career and reputation on the up, Rogerson was transferred to the armed hold-up squad, where shared professional interests saw him befriend two notorious criminals, Arthur Stanley “Neddy” Smith and the Melbourne-based hitman Christopher Dale “Mr Rent-a-Kill” Flannery.

Rogerson also formed a long and fruitful relationship with Sydney crime boss Louis Bayeh, who told the Wood Royal Commission into the NSW Police Service that he had once given Rogerson $1000 towards his daughter’s wedding.

It was through Neddy Smith that Rogerson made the acquaintance of heroin dealer Warren Lanfranchi and Lanfranchi’s lover, Sallie-Anne Huckstepp.’

When Lanfranchi was named as an accomplice in a series of armed robberies, Smith and Rogerson feared that he might be tempted to cut a deal, rolling over and telling the police what he knew about Smith’s heroin operation and about Rogerson’s corrupt links with Smith.

Smith arranged a meeting between Lanfranchi and Rogerson in inner-city Chippendale, ostensibly to discuss a bribe. To show that he was unarmed, Lanfranchi had been told not to wear a coat. On June 27, 1981, Rogerson and Lanfranchi walked together into Dangar Place, where 18 police officers were ready to arrest him. Rogerson saved them the trouble by shooting Lanfranchi dead.

The NSW Coroner found that as a matter of law there was no evidence upon which he could find that an indictable offence had been committed, but the jury was unconvinced, declining to find that Rogerson had shot Lanfranchi in the course of duty or in self-defence.

While Lanfranchi was no longer a threat to Rogerson, Sallie-Anne Huckstepp was. Three weeks after her lover’s death, she had gone to Police Headquarters in Darlinghurst and given a statement to detectives from Internal Affairs in which she promised to tell them “everything” she knew about corruption in the drug and armed hold-up squads.

On the evening of February 6, 1986, Huckstepp was invited to a meeting with drug dealer Warren Richards.

Around 8.45 the next morning her body was found floating in Busby’s Pond in Sydney’s Centennial Park. She had been strangled, dragged into the pond and drowned. Few had a better reason for wanting her dead than Neddy Smith and Roger Rogerson.

Nearly three decades later, Rogerson hooked up with another crooked mate, former Kings Cross detective Glen McNamara, to murder drug dealer Jamie Gao after luring him to a Padstow storage unit in a plot to steal nearly 3kg of methamphetamine. Gao’s body was wrapped in a tarpaulin and dumped at sea, but the two homicide experts botched the job and the body refused to sink.

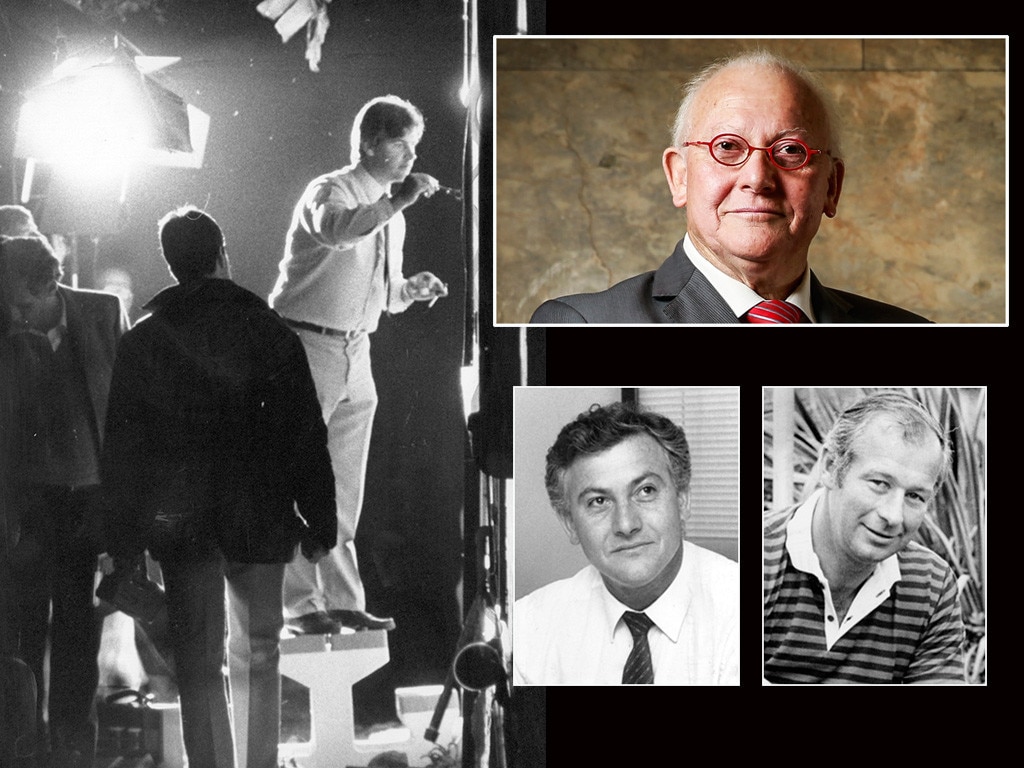

By then Rogerson was long out of the force, having been dismissed from the police in 1986. Accused, but miraculously acquitted, of being involved in the attempted murder of Detective Michael Drury, who had rejected Rogerson’s attempts to bribe him, the Dodger served a few years in jail for perverting the course of justice.

There was no dodging the evidence against him this time and Rogerson and McNamara, each blaming the other, were both convicted of murdering Gao.

At their trial, the judge refused to allow McNamara to tell the jury about an alleged invitation by Rogerson for McNamara to write a book about six murders Rogerson claimed to have been involved in (the book was to be written after Rogerson’s death). Some of it was bluster but not all. While there is no doubt he helped organise the shooting of Drury, he did not pull the trigger and had taken the precaution of arranging an alibi.

And while Rogerson might have approved the murder of Sallie-Anne Huckstepp, it was probably Neddy Smith who killed her.

As for the crimes Rogerson will take to his grave, one involved a contract to murder a senior NSW police officer against whom Rogerson had long held a grudge. Tipped off about the plot against his life, the would-be target made his own unorthodox arrangements with interested parties to ensure that Rogerson never carried out his threat.

Rogerson was a hard man, no doubt, but he was never the hardest man in town.

Tom Gilling is the co-author, with Clive Small, of several books about organised crime

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout