‘Roger Rogerson’s been in my thoughts’: Mick Drury speaks out as his corrupt nemesis faces death

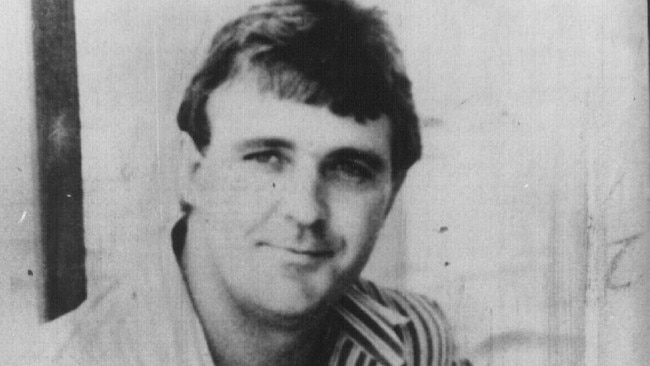

Former policeman Mick Drury has thought about Roger Rogerson – the colleague who tried to have him killed – every other day.

Michael “Mick” Drury sits on the edge of a couch in a house surrounded by the lush rolling hills of the NSW Northern Rivers, leaning forward in thought, elbows on his knees, working out what to say about the man who tried to murder him – Roger Rogerson.

Drury, now 70, was an eager, honest police officer in Sydney in 1984. He was raising a young family. He had a promising future in a job he loved. Not just loved but felt privileged to be a part of. Then at 6.10pm on June 6, two shots were fired through a window of his home in Chatswood on Sydney’s lower north shore.

The bullets narrowly missed his children but struck Drury in his stomach and the side of his chest. He should not have survived given the amount of blood he lost. He remained in a coma for almost a fortnight and was released from hospital after 78 days.

The reason for the assassination attempt? Drury had refused to take a bribe in a major drugs case against criminal Alan Williams. Williams in turn allegedly hired Christopher “Mr Rent-a-Kill” Flannery and NSW detective Rogerson to murder Drury.

Williams would later tell the Supreme Court he attempted to bribe Drury, through Rogerson, to have his drugs charges dropped. Williams ultimately pleaded guilty to conspiring to murder Drury. Rogerson was later charged with bribery and conspiracy to murder but was acquitted. Flannery disappeared and was presumed murdered in 1985. His body has never been found.

On Sunday, Drury, dressed casually in a short-sleeved shirt brightly decorated with leaves and orange and yellow blooms, khaki shorts and thongs, took his time answering what he might say to Rogerson, who has died after suffering an aneurysm in Long Bay jail late last week.

Drury fiddled with his red-rimmed spectacles and finally said: “Well, it’s certainly brought a lot of matters back into my mind. This is 40 years since I was shot … every other day over those last 40 years, Roger’s been in my thoughts.”

Drury is a beloved member of his local community in the Northern Rivers, an avid gardener, an internationally recognised stamp collector and a man of relentless good humour. But when he thinks of Rogerson, his face is momentarily drawn, thrown back to an extraordinarily painful period in his life. And it’s not just the memories of his own near-death experience, but that his attempted murder was sanctioned by a police colleague. To this day he remains incredulous that a fellow officer tried to have him killed.

“Look,” Drury added, “when I first thought about Roger’s current health position, quite frankly my thoughts and prayers went to his family because it’s a very delicate and a very difficult time for his family. And I really appreciate that. And I say with great honesty that my prayers are with (his) family in this difficult time.” He said he hoped no other young police officer would ever have to go through what he did.

“Being a police officer in New South Wales or Australia is a wonderful, wonderful vocation,” he said. “It’s a vocation whereby I was paid to protect people. And at the same time I could go out and work on crooks, arrest them, and put them before the courts to be dealt with by magistrates and judges in accordance with the law.

“Unfortunately, Roger Rogerson and a couple of others have really brought discredit upon the vocation. They have betrayed the people of NSW and Australia.”

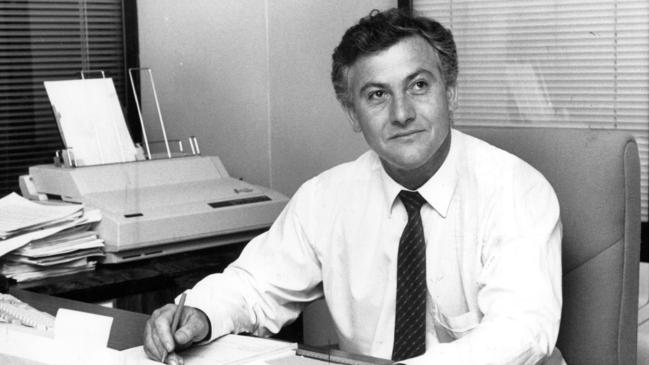

Drury of course knew of Rogerson as a young recruit. He said the famous, and highly decorated, detective was “powerfully connected”.

Rogerson’s death, however, will deny Drury’s hope that he could have sat down with the killer (In 2016, Rogerson was convicted of the murder of drug dealer Jamie Gao in Sydney two years earlier) and asked him to tell the truth about his criminal career.

“I’ve intentionally stayed away until all the legal issues (including Rogerson’s recent unsuccessful appeal against his murder conviction in the Gao case) were exhausted,” Drury said. “There was a wonderful opportunity there to solidify some amazing Australian history. I believe he would be truthful with me. I would have stood up and shaken his hand on national TV and forgiven him for what he’d done because he told the truth. I would forgive him.”

That opportunity may now be lost.

After suffering his medical episode last Thursday night, Rogerson was transported to Randwick’s Prince of Wales Hospital and his life support was reportedly turned off on Friday morning.

The tail of carnage he has left in his wake, however, is long.

‘He turned bad’

Rogerson joined the NSW police force in the late 1950s in Bankstown, western Sydney, and showed an uncanny aptitude as an investigator. He was quickly transferred to the Criminal Investigation Branch before really making his name in the 1970s in the armed holdup squad.

It was at this moment his professional life directly intersected with some of Sydney’s heaviest criminals, including Arthur “Neddy” Smith. Rogerson of course made headlines when he shot dead drug dealer Warren Lanfranchi in June 1981.

Somehow, a brilliant career had entered the shadows.

Chris Hannay, a former NSW drug squad officer and now head of legal firm Hannay Lawyers, left the force in 1989 but remembered Rogerson from his days working the Sydney streets.

“He was just a bloody good policemen who could have risen to commissioned ranks,” Hannay said. “It’s like a switch in him turned off. He turned bad. The division between what he was and what he became was pretty profound.”

Hannay said he had no doubt Rogerson was a psychopath.

“Behind the normality was just something running in his head,” Hannay said. “No scruples, no emotion, nothing. Just an absolute psychopath.”

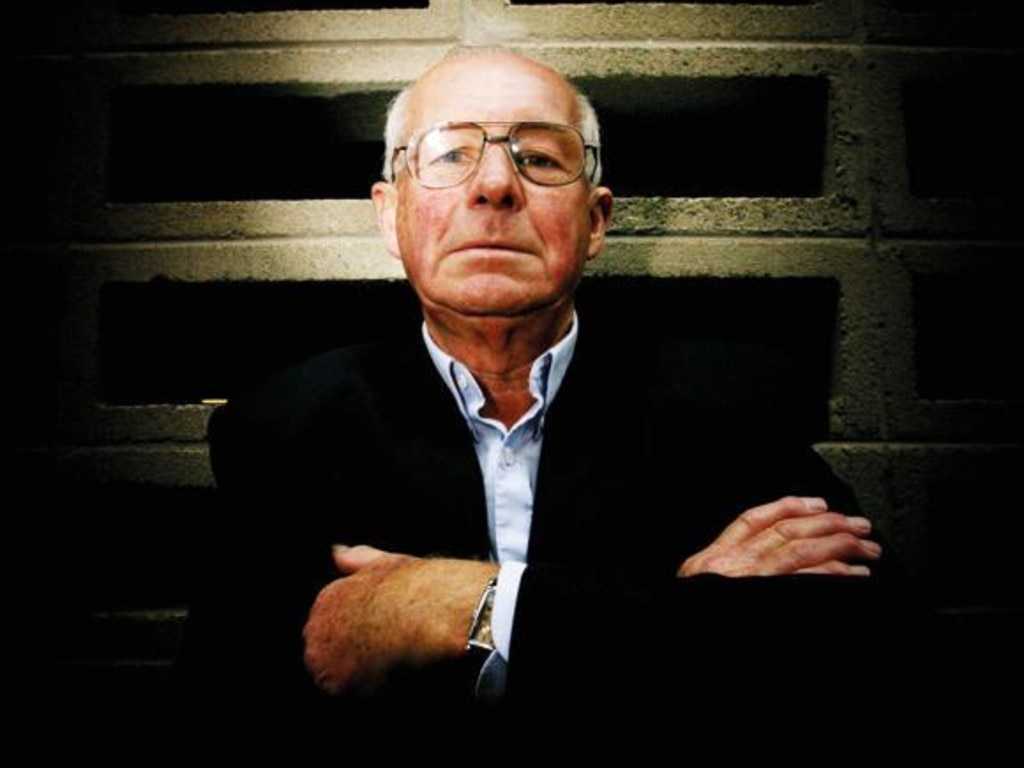

Duncan McNab, former NSW detective and the author of the biography, Roger Rogerson, said Rogerson had been in poor health for years and “he could see the grave opening up before him”.

“He’s been in pretty poor pretty mechanical shape for over a decade,” he added. “I heard that in the last couple of months he’s been pretty much wheelchair-bound and can barely lift his arms and that sort of stuff. And physically he was starting to deteriorate as well. So the nuts and bolts were breaking up. The fact that he had an aneurysm or strokes the other night comes as absolutely no surprise.”

McNab still remembered the first time he encountered the infamous “Dodger”.

“I was very, very young at the CIB,” he said. “Roger would always come up and say hello to the new fresh faces and get to know them. He was fabulous. Charismatic. You thought ‘the golden boy wants to talk to me’. You felt you’d joined a very small club, and Roger was great at that. He’d remember your name. He’d remember a few things about you, blah, blah, blah. Oh, the politician’s gift.

“He’ll be fondly remembered by a few, and as an evil, corrupt, manipulative bastard by anyone who actually had any dealings with him.”

Even on the brink of death, Rogerson still had a few loyalists.

His impending demise prompted some praise, condemnation and lasting debate on social media pages over the weekend. “RIP ROGER. Right or wrong you did it your way!” one former police officer wrote. “Like him or not, Roger Rogerson was a bloody good detective. I have my ‘conspiracy’ things on his arrest. Rest in peace brother. You did a great job,” wrote another.

“You are joking. He’s a convicted murderer,” said yet another, and on and on it went.

Others were unequivocal about his legacy.

‘Justice to die in jail’

Kathleen Flannery, wife of Christopher Dale Flannery, told The Australian it was justice that Rogerson die in jail.

“He will die the way he deserved to die,” she said from her home on the Gold Coast. “What else can you say? You know, justice is done.”

Her husband might have been dubbed Mr Rent-a-Kill, but Rogerson, she said, was Mr Rent-a-Cop. “Chris said you couldn’t trust Rogerson as far as you could throw him,” she said. “But Rogerson was useful. It was business. Rogerson would do anything for money. Husband. Wife. Children. It didn’t matter. He was absolutely a psychopath. He had no soul.”

When asked who she thought killed her husband in 1985, she said without hesitation: “Roger.”

During my research into the murder of Sydney gangster Stewart John Regan in Sydney in 1974, I was assisted by Regan’s own cousin, former NSW police officer Kelly Slater Regan.

Kelly Regan contacted several retired police officers about Regan’s death and one recalled something he heard back in the 1960s. He said in a text message: “There was always a rumour circulating about an assassin in the CIB … (going back to) the early days, 1950s, ’60s, and maybe ’70s”.

Police ‘assassin’?

The officer was suggesting that each generation of police had a killer in its ranks, or someone who, when tapped on the shoulder, was prepared to murder when required.

Queensland’s corrupt police past certainly pointed to generational assassins, including Detective Glendon Patrick Hallahan (an acquaintance of Rogerson) through the 1950s and ’60s.

Was Rogerson his generation’s “assassin”?

“I wouldn’t disagree with that at all,” Duncan McNab said. “I would have thought there might be a couple of them. Look at (former NSW detective) Fred Krahe, he’s the perfect example. There’s power in that, and there’s sometimes a lot of money in that as well. And the prestige. “I don’t know that much about Queensland, but certainly New South Wales had Roger Rogerson.”

I interviewed Rogerson several times on the phone before he went to jail for the Gao murder when I was researching true crime history in Queensland, and he was not just affable but appeared to go out of his way to help me with my work. He loved yarning about the past and showed all the theatrical flare he must have used on those pub tours he made in his retirement, telling tough, blokey, often deadly tales to a receptive public. Here he was, the killer cop, giving the inside scoop.

I found Rogerson’s photograph in the private album of former corrupt police commissioner Terry Lewis when I was researching Lewis for my books. It was a picture of Rogerson enjoying the hospitality of senior Queensland police at a farewell party in the late 1970s in Brisbane. What Rogerson was doing there with some of Queensland’s most notorious corrupt police has remained unexplained.

Rogerson’s role in the investigation into the horrific firebombing of the Whiskey Au Go Go nightclub in Brisbane in 1973 remains questionable. Fifteen people perished in the fire. Rogerson was asked to help Queensland police catch the perpetrators and was present when two career criminals – John Andrew Stuart and James Finch – confessed to the crime.

To this day those unsigned statements remain contentious, as does the allegation that Rogerson helped verbal the prisoners.

Two years ago Rogerson was called as a witness into a renewed coronial investigation into the Whiskey mass murder.

Appearing via video link from prison in Sydney, Rogerson was asked to swear an oath before giving evidence. He told the court: “I swear not to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.”

A clown to the end.

A psychopath with a badge who ended and ruined lives. In our final phone conversation, Rogerson confided in me: “Len McPherson said to me once – Roger, you can control a bad man, but you can’t control a mad man.”

I only now understand that Roger Caleb Rogerson was actually describing himself.

This week, Mick Drury will take to his mower and trim the paddocks of his farm, working methodically in sections, carving perfect lines and curves in the green grass. He’ll go on a “stick” patrol and clear his fields of tree detritus following a string of summer storms. He will wave over the fence to neighbours, offer help where he can, share a funny story from his past.

He may, amid all of this goodwill and kindness, think for a moment of Rogerson.

Soon, though, he might not have to think of him at all

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout