He completed a PhD in economics at Harvard, in 1962, on decision-making under uncertainty and demonstrated striking originality and brilliance in his work. But he had already, by then, spent years working on top-secret matters for the US government; above all, on nuclear strategy, deterrence theory and command and control. This was the cutting edge of his thinking.

It was these things that haunted him most: problems of nuclear arsenal command and control, how to think rationally and responsibly about nuclear deterrence, how to avert nuclear war under conditions of uncertainty and confrontation, how to de-escalate the nuclear arms race.

In the Prologue to The Doomsday Machine, Ellsberg related how, in the spring of 1961, he learned from specific Pentagon answers to questions he asked on behalf of the Kennedy White House that existing American nuclear war plans, if acted on, would kill 600 million people in Europe and Asia.

That’s “a hundred Holocausts”, he thought. This was “evil beyond any human project ever”. “From that day on,” he commented, “I have had one overriding life purpose: to prevent the execution of any such plan.” He is gone but, despite the Cold War ending, such dire fatalities remain unnervingly possible.

When, in 1971, he copied and leaked seven thousand pages of classified material on the Vietnam War – the Pentagon Papers – he also copied and intended to leak eight thousand pages of classified documents on the Pentagon’s planning for nuclear war against the communist world.

But this didn’t become clear until almost the end of his life. He only published that story in his 2017 memoir, The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner. Prior to that, he published Papers on the War (1972), a classic set of essays analysing the decision-making in the Vietnam War; then, after a very long hiatus, Risk, Ambiguity and Decision (2001) and Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers (2003). For much of the time, in between writing these books, Ellsberg campaigned actively and often against war and government secrecy. In his last days, this year, he condemned Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine unequivocally, saying: The Russian invasion of Ukraine has made the world far more dangerous, not only in the short run, but in ways that may be irreversible. It is a tragic and criminal attack. We are seeing humanity at its almost worst, but not quite the worst – so far, since 1945 we haven’t seen nuclear war.

Yet Putin has repeatedly threatened to use nuclear weapons at his own discretion and cause what he himself has described as “a global catastrophe”. That’s the territory we are in right now. The strategic thinking required is immensely challenging. Despite the various efforts at nuclear arms control or reduction, we now live in a world in which the US and Russia both have large nuclear arsenals (albeit far smaller than at the height of the Cold War), China is racing to achieve nuclear parity with those two powers; Britain, France, Israel, India, Pakistan and North Korea have nuclear weapons.

Iran is edging towards acquiring them, which could trigger uncontrolled nuclear proliferation in the Middle East; and South Korea’s President has warned that similar nuclear proliferation would occur in Asia, should the US do what China is seeking to make it do – withdraw its security umbrella from East Asia.

All of this, and the perilous possibilities it entails, must have been on the mind of the dying Ellsberg throughout his last months. In Secrets, he hinted that he had a book in him about nuclear weapons, but it was 14 years before that book was published. I reviewed it in the pages of this newspaper in early February 2018. I declared then, and reiterate here, that The Doomsday Machine is compelling reading and ought be required reading for any responsible adult in our time.

Now, more than ever, is the time to read what Ellsberg knew and how he thought about decision-making under uncertainty in a world of nuclear arsenals. We are all, more or less, aware that we live in a dangerous world. But nuclear weapons, though they hang over us like a proverbial sword of Damocles, represent a more than usually thorny problem.

As Serhii Plokhy showed in Nuclear Folly: A New History of the Cuban missile crisis (2021), decision-makers in Washington, Moscow and Havana, in 1962, miscalculated odds, took extraordinary risks, misunderstood facts on the ground and the intentions or motives of others, and took the world right to the brink of thermonuclear war. That was Ellsberg’s terrain.

Fred Kaplan, in The Bomb: Presidents, Generals and the Secret History of Nuclear War (2020), drawing chiefly on the US case, brought the matter up to date. But Ellsberg was the analyst, the insider, the moral conscience and the memoirist who dissected this for us all. One would like to say, rest in peace, Dan Ellsberg. But there is no peace. The danger is real, present and all but intractable.

Paul Monk is a former senior intelligence analyst and author of Thunder From the Silent Zone: Rethinking China.

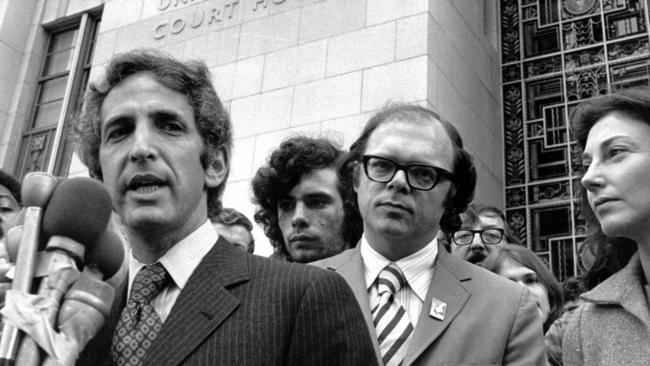

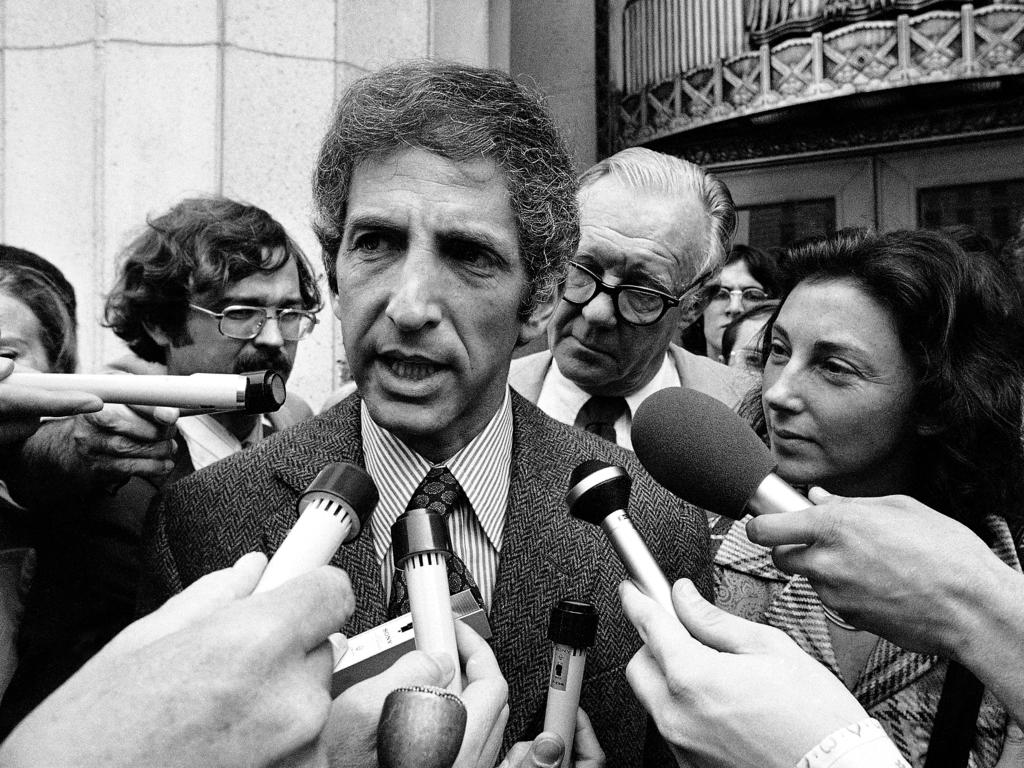

Daniel Ellsberg died this time last week, aged 92. It is half a century since he leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times, triggering a landmark arm wrestle between executive authority and the free press in the US. But he was much more than that. The Vietnam War was only the tip of an iceberg – or the tip of Ellsberg, if you will.