Daniel Ellsberg: the first whistleblower

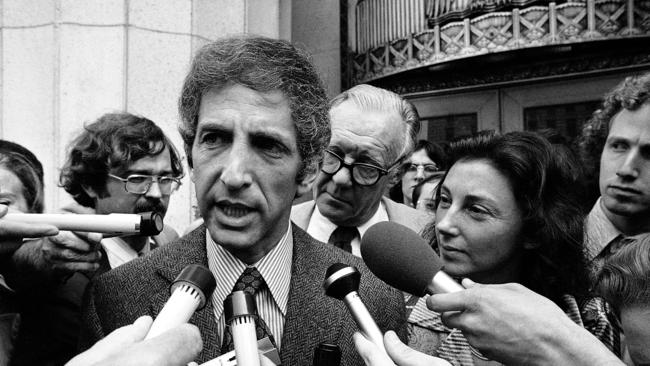

Daniel Ellsberg was once called ‘the most dangerous man in America’.

When the Pentagon Papers were published 50 years ago by The New York Times – disclosing a top-secret history of the Vietnam War that revealed successive US presidents had lied about the conduct of the war – whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg did not think it would have much of an impact.

But that 7000-page study of decision-making in the Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson administrations was the largest leak of classified documents in US history. It sparked a landmark battle over press freedom, inspired generations of future whistleblowers and led to the downfall of Richard Nixon.

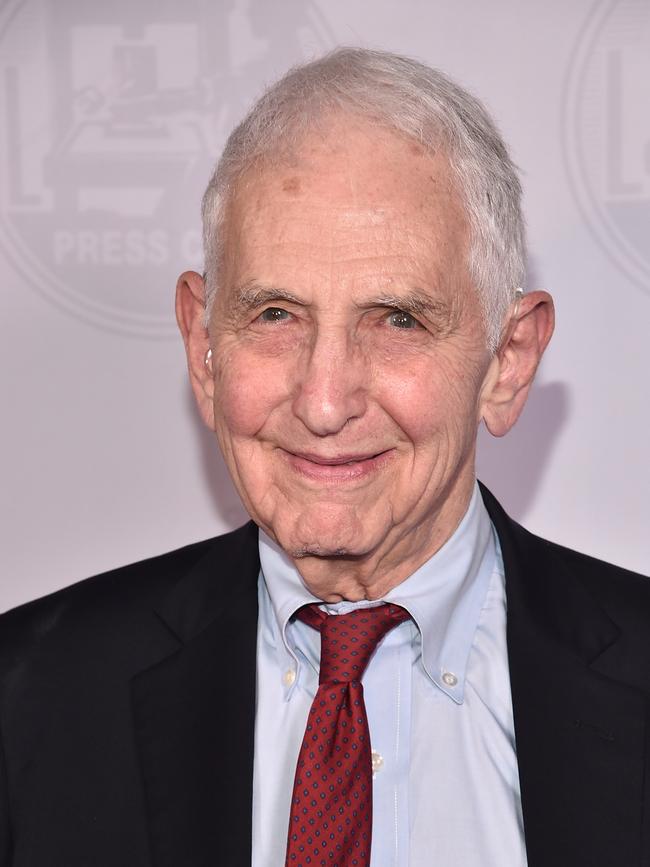

“There was no immediate impact on the war because, although the Pentagon Papers did further disillusion the public with the war, it was already disillusioned, and that was having no effect on Richard Nixon,” Ellsberg, 90, tells Inquirer in an exclusive interview.

“The year after they were published came the Spring-Summer Offensive of the Hanoi government and then, by December of 1972, a year and a half after the Pentagon Papers came out, was the heaviest bombing of the war. So, the impact seemed to be that it had no effect on the war.”

Indeed, Nixon’s initial reaction was not to take the leak of the report by the Vietnam Study Task Force established by Defence secretary Robert McNamara all that seriously.

After all, it covered the period 1945 to 1968, ending before Nixon became president in 1969.

But Henry Kissinger, the US national security adviser, was alarmed. He called Ellsberg “the most dangerous man in America”. That got Nixon’s attention. He feared Ellsberg had other documents that could be damaging to Nixon, including about his secret bombing of Cambodia. Nixon told his chief of staff, Bob Haldeman, to “use any means” necessary to “destroy” Ellsberg.

“Nixon was afraid I would publish information on his administration,” recalls Ellsberg. “So the war went on but meanwhile Nixon had committed a number of crimes against me, to shut me up, to keep me from revealing what documents I might have, and so that did lead to Nixon leaving office and made the war endable.”

Ellsberg’s journey from hawk to dove began in Vietnam. He had served in the Marine Corps and earned a PhD from Harvard. His focus of study was decision theory and he became an expert in nuclear weapons. He spent a week in Vietnam in 1961 and two years there, from 1965 to 1967, working for the State and Defence departments studying counter-insurgency.

“In 1961, it was already clear that if we sent troops we would suffer the same fate as the French; namely, bogged down in a stalemated, hopeless war,” Ellsberg says. “And so I came to believe that American leaders would sacrifice almost any number of lives to avoid losing a war or losing an election.”

Ellsberg, having worked as a special assistant to McNamara, was invited to work on the Vietnam study while employed at the RAND Corporation think tank in 1967. The archival documents confirmed his concerns about the war.

By 1969, it became clear Nixon would not withdraw from Vietnam. Ellsberg formed friendships with anti-war protesters, including Anthony Russo, and turned dove.

“Nixon was going to be the fifth president to follow this same pattern,” Ellsberg says. “All I had was the evidence that four previous presidents had made the same kind of gamble, which was why we were where we were in Vietnam. I wanted to do anything I could to shorten the war.”

RAND had one of the 15 copies of the top-secret 47-volume Vietnam study. In October 1969, Ellsberg went to RAND, took several volumes from the safe and stuffed them into his briefcase. He walked nervously past security and exited the building. He then went to an advertising agency where Russo’s girlfriend, Lynda Sinay, worked and began copying the study on a Xerox machine. After doing this a few times, any nervousness subsided with the belief that it was “the right thing to do”.

After failing to persuade Democratic senators William Fulbright and George McGovern to make public the Pentagon Papers, Ellsberg decided to leak the study to the NYT. In March 1971, Ellsberg met with reporter Neil Sheehan. Ellsberg told Sheehan he could read and take notes of the study but would not give him a copy until the NYT agreed to publish the actual documents.

Sheehan, however, feared he was going to be scooped so began copying the documents. A team of reporters was assigned to the story and worked secretly from the Hilton Hotel in New York. Ellsberg found out that a story was imminent and went into hiding. Ellsberg knew Sheehan had secretly taken volumes to copy without permission.

“When I learned he had copied them, it didn’t offend me particularly as I thought he had done what I had done,” Ellsberg says. “I still can’t understand why he refused to tell me that the Times were in fact working on these documents. I was doubtful they would publish them and so all I wanted to hear was that they were.”

On Sunday, June 13, 1971, the NYT revealed the top-secret study in an above-the-fold article titled “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement”. Sheehan reported that:

… four succeeding administrations built up the American political, military and psychological stakes in Indochina, often more deeply than they realised at the time, with large-scale military equipment to the French in 1950; with acts of sabotage and terror warfare against North Vietnam beginning in 1954; with moves that encouraged and abetted the overthrow of President Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam in 1963; with plans, pledges and threats of further action that sprang to life in the Tonkin Gulf clashes in August, 1964; with the careful preparation of public opinion for the years of open warfare that were to follow; and with the calculation in 1965, as the planes and troops were openly committed to sustained combat, that neither accommodation inside South Vietnam nor early negotiations with North Vietnam would achieve the desired result.

The Papers also revealed damaging secrets about the decision by the Menzies government to send Australian combat troops to Vietnam in 1965. Robert Menzies said the decision to send troops was in response to a request from the South Vietnamese government. In truth, Australia offered to send forces before any formal request came from South Vietnam or the US.

“One of the things held against me when I was on trial was that I had embarrassed allied governments,” Ellsberg says. “When I heard that Australia had instituted the draft [conscription] in order to go to Vietnam, I thought ‘Boy, do those people deserve to be embarrassed’. I was shocked that a country would draft its people to go to Vietnam to maintain an alliance.”

After three days of reporting, the Nixon administration secured an injunction halting further publication in the NYT. Ellsberg then leaked the Pentagon Papers to the Washington Post, and when they were stopped, to 17 other newspapers. The legal fight went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favour of the newspapers, enforcing the First Amendment principle of freedom of the press on June 30.

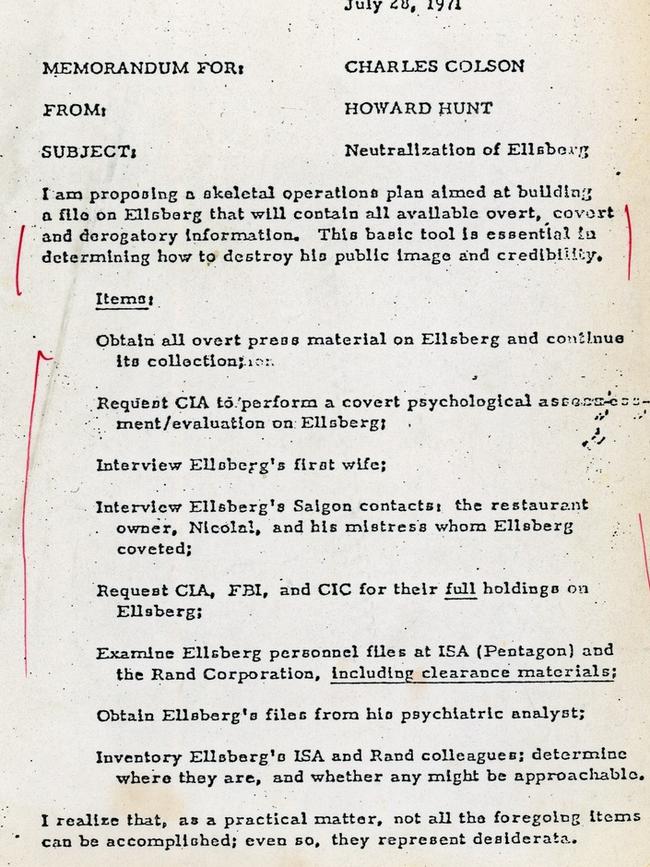

Nixon had told his aide, Chuck Colson, to “hang the son of a bitch” Ellsberg. Colson engaged former CIA operative Howard Hunt. On July 28, Hunt sent Colson a memo titled, “Neutralization of Ellsberg”. It outlined a chilling strategy by the White House “Plumbers” to “destroy” Ellsberg’s “public image and credibility”, including burgling the office of his psychiatrist, Lewis Fielding, in search of incriminating files.

“Yes, they were fearful,” Ellsberg recalls. “They really thought I was a danger to their secret foreign policy, and I was; but unfortunately I didn’t have the documents to prove it.”

Ellsberg turned himself in and, with Russo, was indicted under the Espionage Act. But when it was discovered the government had used illegal wire-tapping and burglary to undermine Ellsberg’s defence, all charges were dismissed on May 11, 1973.

The Plumbers, however, had been busy elsewhere. On June 17, 1972, they broke into the Democratic National Committee HQ at the Watergate building in Washington DC. That would lead directly to Nixon’s resignation two years later. The US withdrew from Vietnam on April 30, 1975.

The public right to know about their government is as important as ever. Ellsberg praises Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning, and says the Australian government should be ashamed of the lack of support it has given to Julian Assange. But he counsels whistleblowers to consider disclosing secrets anonymously if they can, given the harsh treatment they can expect to face.

“If you have information that might avert a wrongful war or might preserve democracy, then you should consider, even at very great personal risk or cost, revealing that information,” Ellsberg says. “It is not to be considered lightly and it is not something to be done where the stakes are not very high. The question is: ‘What are governments lying about and where is it leading?’.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout