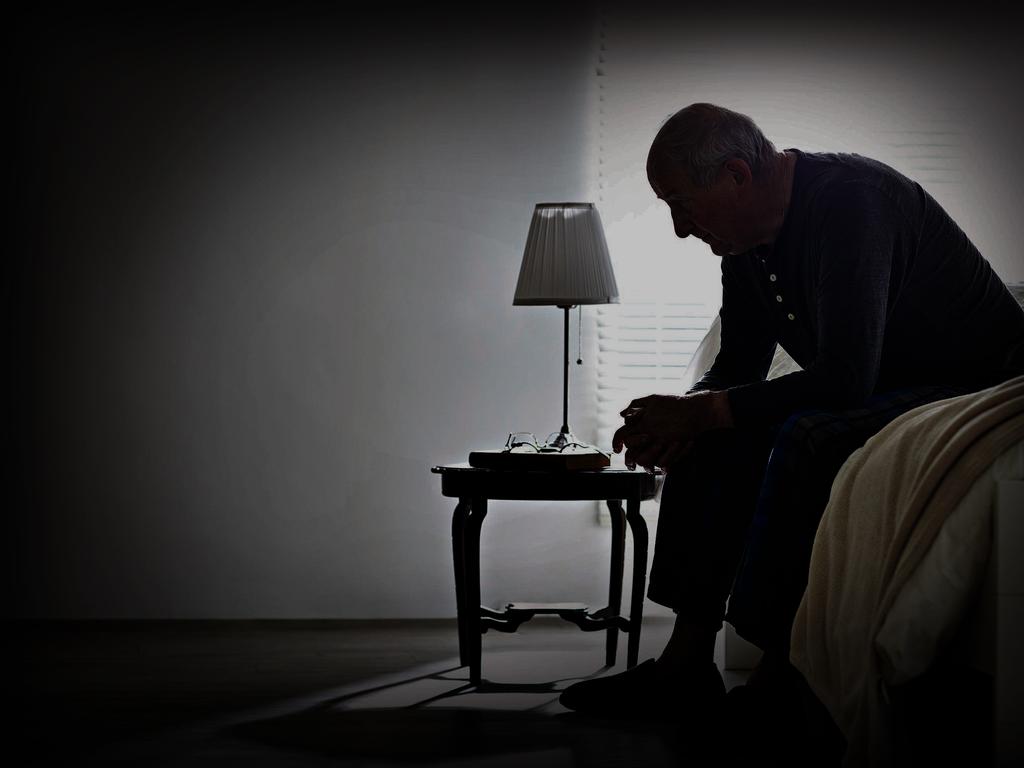

Silent killer: older Australian men are experiencing loneliness more than ever

A group of Australians at special risk of experiencing loneliness is older men. Yet most people – doctors included – don’t recognise the huge effect it is having on their lives and health.

There’s a condition that can take years off your life and set you up for a raft of medical problems. Older men are most at risk for the condition and, at the moment, we’re in an escalating epidemic of it. Yet most people – doctors included – don’t recognise the huge effect it is having on our lives and health.

That condition is loneliness.

There is strong evidence that Australians are experiencing loneliness more than ever. A group at special risk is older men – with the decade from age 55 to 64 being a time of special risk according to recent statistics from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

The institute’s figures point to almost one Australian adult in six experiencing prolonged loneliness. This is very similar to findings from countries such as Norway and the United States.

Indeed, so concerning is the global trend to loneliness that the World Health Organisation has described the situation as a major public health concern.

For these reasons the Australian organisation Ending Loneliness Together is calling for a national strategy to address the problem.

Aside from the health and compassionate concerns society should have about the “epidemic” of loneliness, economic research from Australia suggests that the health effects of loneliness may cost the economy as much as $2.7bn every year.

All of us need human connection not only to thrive but also to survive. Loneliness is the sometimes intense feeling of being alone or separated from others. While social isolation is closely related, it is possible – indeed common – to be lonely in the midst of many people.

Loneliness can be miserable for people to experience, but ill health flowing from being lonely can make everything worse.

It is startling to realise that long-term loneliness increases your chance of an early death by 26 per cent – the same effect as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

So concerning are the health effects of loneliness that the US National Academies of Sciences has warned that “social isolation presents a major risk for premature mortality, comparable to other risk factors such as high blood pressure, smoking, or obesity.”

Loneliness now has been linked to illnesses such as heart disease and stroke, diabetes, mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety – even suicidality – as well as alcohol misuse and other additions. Dementia and other cognitive problems also are known to flow from long-term loneliness.

Why are we seeing such a wave of loneliness and health consequences flowing from it?

There is no doubt that the pandemic increased social isolation for many people, but loneliness was an issue before Covid-19 took to the stage. Part of the reason is that Australians are ageing and many of us are relying on digital connection rather than direct human contact.

Things that can have a powerful effect on causing loneliness including loss of mobility and difficulties in moving around. Untreated problems with vision or hearing are major contributors as people lose confidence in connection and communication.

Living in isolation has become an increasing trend in Australia. This is made worse if people have problems accessing transport or if they lack social support with getting out of their home. Cost-of-living issues are seeing many older Australians forgoing trips out and social events or joint meals.

The loss of a life partner – either their death or a need for care in a hospital or other care setting – can be very isolating. Divorce and relationship breakdowns can have a severe effect both on mental health and other friendship groups.

People already experiencing failing health, and those with a disability – especially Australians living in rural areas – may be at particular risk. People without children are another increasing trend, and those who have problems with social media connection.

Accepting that loneliness is a common problem for many people in our community, and that it has enormous potential effects on individual health and the broader economy, it may surprise you to learn that the medical research on what to do about loneliness is scant indeed.

Recognising these risks, it is vitally important that if you are experiencing loneliness that you let your doctor know. There should be no shame in talking about how you feel and how loneliness is affecting you. Your doctor needs to know.

That said, much of the solution clearly is beyond the realm of medicine alone. The US National Institute of Ageing has some excellent tips on managing loneliness. The critical first step is recognising the problem, understanding that is it common, and that it puts you at risk.

It is easy to neglect self-care when you’re lonely. As basic as these things seem, focusing on sleep, gentle physical activity, and eating healthily are an important start. Make sure you work with your doctor on this if you have been neglecting your health for a long time.

Re-connecting can be a challenge for many lonely people – it is very easy to lose confidence.

Volunteering can be a powerful way of giving yourself back a sense of purpose and meeting and building relationships with like-minded people. In fact, there is research to support the effects of volunteering in boosting your mood and strengthening your mind and body.

Recognise that everyone – all of us – seeks human connection. Make the time to call, text, or even write to family, friends or neighbours. So often you’ll be surprised how people will respond.

Think about joining a walking club, a church or other faith-based group, and check with local community organisations.

If you’re an older Australian man then you’re in a risk group for this most pernicious of conditions. Loneliness can affect anyone at any age, though. It can be tough to admit it has entered your life, but recognising it can save your life.

Steve Robson is professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at the Australian National University and former president of the Australian Medical Association. He is a board member of the National Health and Medical Research Council and a co-author of research into outcomes of public and private maternity care.

This column is published for information purposes only. It is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be relied on as a substitute for independent professional advice about your personal health or a medical condition from your doctor or other qualified health professional.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout