Thus, the population fatality rate – that is, the number of deaths per 100,000 population – from a normal flu season in Australia is in the order of 0.6, rising to 0.9 in flu seasons that are especially severe.

In contrast, our population fatality rate from Covid, despite being one of the world’s lowest, has been four times that due to the flu in its harshest seasons and at least six times that for a flu season which approximates the norm.

And taking account of what has happened overseas makes the contrast even starker, with the five worst affected advanced economies suffering, on average, 195 Covid-related deaths per 100,000 population – 150 to 200 times the flu’s typical cost in human lives. The difference, however, is not in fatalities alone. There are complications from the flu, including the risk of pneumonia; but those complications are nowhere near as widespread as long Covid seems to be, with its enduring harm to the immune system.

While it is too early to assess the cumulative impacts, Covid seems likely to leave a burden of morbidity for decades to come.

It is, of course, possible that mutations will eventually make Covid less dangerous, as simple evolutionary models would predict. However, the randomness of the mutation process means there is still a substantial probability of variants that are more fatal than the strains that have wreaked havoc globally during the past 18 months.

And even though the treatment of Covid has improved, there remains an enormous gap, both in mortality and in morbidity, between the efficacy of the treatment options for Covid and those for conventional respiratory diseases. As a result, an especially virulent strain could swamp health systems – unlike the flu, whose range of variation is both quite narrow and relatively well understood, allowing the risk of a particularly bad season to be taken into account in planning hospital capacity.

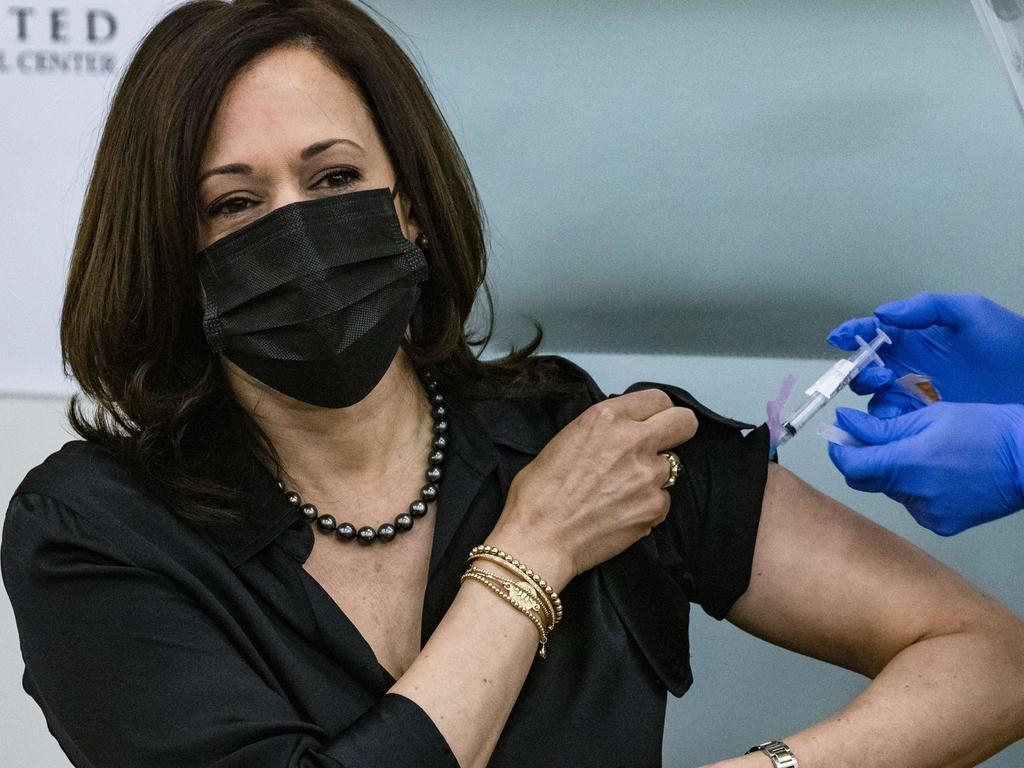

All that makes widespread vaccination the key to bringing Covid durably under control and breaking the endless cycle of lockdowns. Yet in that respect, too, the challenges are substantially greater than those from the flu.

That is partly due to Covid’s novelty, which means vaccination systems have largely had to be built from scratch. But the problems are compounded by the complexity of the vaccines, which usually require two doses and, for some of those based on messenger RNA, elaborate distribution arrangements.

Moreover, while flu vaccines are typically targeted at the older and most vulnerable groups in the population, effective protection from Covid requires nearly universal coverage, greatly extending the reach vaccination programs must achieve.

It is consequently unsurprising that virtually all the OECD countries have struggled to get well-functioning vaccination programs in place, despite their sophisticated health infrastructures. Doubtless, some governments have made more mistakes than others, with those of our own featuring prominently in the political football to which Australians are addicted; but the evidence suggests the greatest factor affecting vaccination rates is not differences in delivery programs but the extent of the Covid mortality to date.

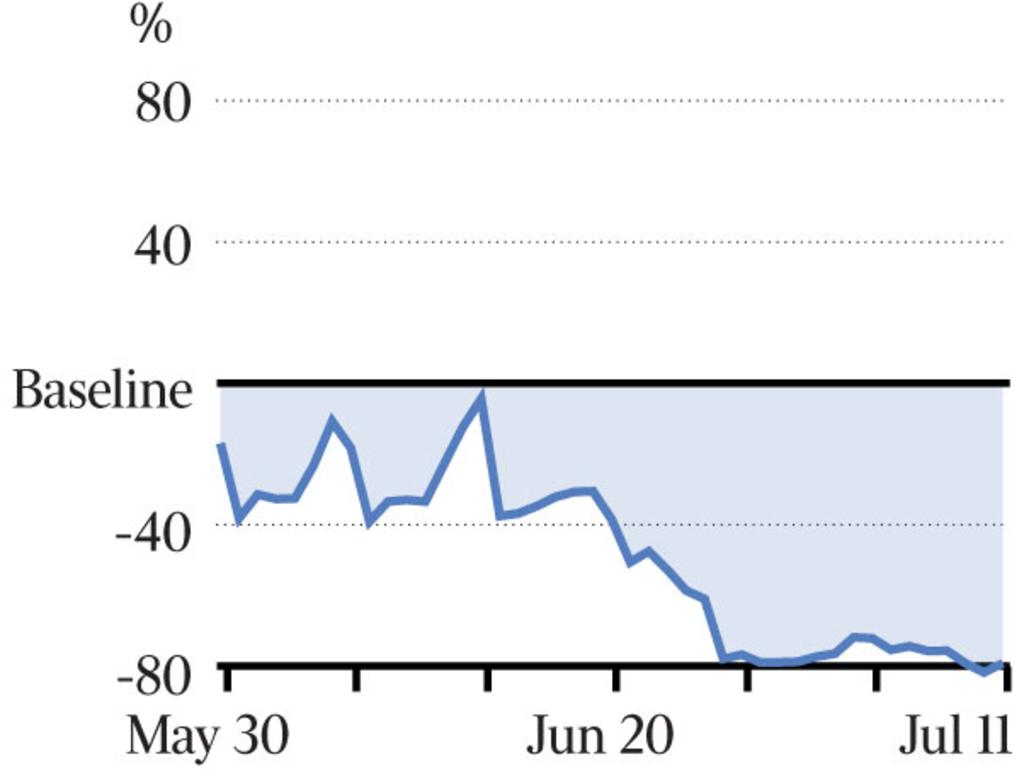

A comparison between the OECD economies that experienced the highest and the lowest population fatality rates makes the point: on average, the five that suffered the most from Covid have twice the vaccination rate of the five that suffered the least.

And viewed statistically, the picture is even sharper: by themselves, variations in population fatality rates explain fully half the variation between advanced economies in vaccination rates.

We are, to that extent, victims of our capacity to keep the disease at bay, as are New Zealand, Japan, South Korea and Finland. It may be that success in containing the virus led governments to place less stress on developing effective vaccination programs; but it is also likely that the very low risk of catching Covid induced some complacency in the population, easing the pressure on governments to ensure vaccination was readily available and reducing the demand to be vaccinated even where it was.

The extent of those effects on demand is inherently hard to measure. However, it is striking that neither Australia nor the other low-fatality countries have seen the interminable queues that clogged vaccination centres in their high-fatality counterparts.

And adding to the impression of complacency, vaccination rates in the low-fatality countries remain relatively low even among the over-65s, for whom supply constraints have rarely been an issue.

Whether the Sydney outbreak durably changes matters remains to be seen.

There is, for sure, an immediate effect on take-up driven by Covid’s greater salience and by improved access to vaccination. The risk, however, is that the shock will wear off, leaving us in a situation in which Australian governments – faced with a largely unvaccinated population – continue to view lockdowns as their only option whenever Covid strikes, quite regardless of the outbreak’s scale.

The fact that vaccination rates now seem to be plateauing even in the countries that experienced very high population fatality rates underscores that risk, highlighting the difficulties of securing the comprehensive coverage we need.

Clearly, one response is that which France’s President Emmanuel Macron unveiled on Monday night, effectively making vaccination mandatory by largely preventing the unvaccinated from participating in everyday activities such as going to the cinema, eating at a restaurant or cafe, or travelling any distance by train.

It is, however, surely undesirable to take the infantilisation of Western populations, and the erosion of civil liberties, even further than it has already gone.

Rather, the better course is to fully address any remaining constraints on access to vaccines while offering incentives that instead of reducing choice, as mandatory vaccination does, increase it – for example, by exempting the fully vaccinated from our draconian travel restrictions.

At the same time, governments should make it clear to all Australians that Fortress Australia cannot and will not endure forever – and that, as it is progressively rolled back, those who refuse vaccination will be exposing themselves and their families to significant danger.

That requires being honest and direct with the Australian public. The unrelenting alarmism of public health officials, marching in their serried ranks to the Grim Reaper’s habituating drumbeat, helped get us into this mess. It isn’t equally erroneous wishful thinking about the threats and challenges Covid poses that will get us out of it.

It is one thing to say, as I did on these pages last week, that Covid-19 should ultimately be managed like the flu, and quite another to imply that there is little difference between Covid and the flu. Let’s be clear: Covid is not the Black Death. But neither is it merely the flu with some punch added.