The secret to Afterpay’s success: ‘everybody wins’

Nick Molnar used a life lesson from the last financial crisis to build a payments company that’s become a market darling.

Nick Molnar used a life lesson from the last financial crisis to build a payments company that has become one of the stockmarket success stories of the current downturn.

“I had just turned 18 and I was told, ‘Don’t spend money you don’t have’,” Mr Molnar says, recalling an era of bank bailouts, company collapses and residential repossessions.

That advice set the jewellers’ son from Sydney on a path that in 2014 led him to co-found Afterpay, an instalment-payment company that positions its service as a cheaper and more responsible alternative to a credit card.

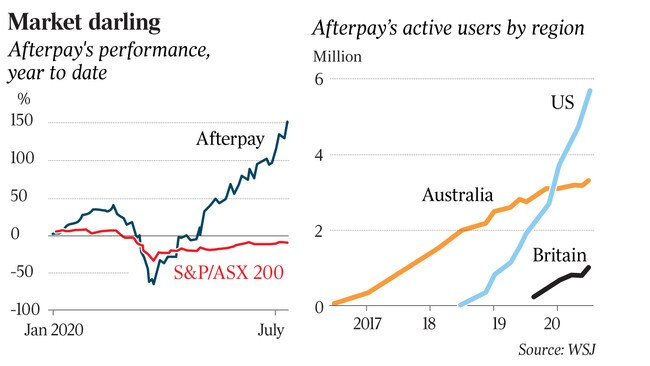

Australia’s largest tech company by market capitalisation — about $US13.5bn ($19.5bn) — Afterpay is expanding across the US through deals with retailers including Anthropologie and Free People. Since the Australian market bottomed on March 23, its stock has risen more than ninefold, while 1.6 million new US users started spending through its technology over the past four months.

Payments is now one of the most vibrant corners of the fintech world, attracting billions of dollars in venture capital and triggering a rearguard action among banks worried that a permanent shift in consumer behaviour is under way. PayPal shares have risen more than 65 per cent year-to-date, giving the company a market value larger than any US bank save JPMorgan Chase, while Square’s market value has doubled in the same time to more than $US50bn.

Afterpay this week raised $US452.6m from institutional investors to expand into more countries. The new shares were priced 6.9 per cent above the floor price, at a level the stock only hit for the first time less than a week earlier.

Afterpay and rivals, including Zip Co, Splitit Payments and Sezzle, are targeting a global payments industry valued at $US1.9 trillion by consulting firm McKinsey & Co. While their slice of income is tiny compared with the $US83.5bn revenue generated by Visa, MasterCard and American Express in 2019, it’s growing fast.

Four years after its debut on Australia’s stockmarket with a market value of $US115m, Afterpay is still losing money. But it has attracted interest from investors including Tencent, one of the two dominant digital-payments companies in China, which this year bought a 5 per cent stake. Tencent’s rival, Alibaba, has also bet on buy-now-pay-later: its finance affiliate Ant Financial bought a stake in Klarna Bank, Afterpay’s Swedish rival, in March.

Afterpay’s technology allows users to pay for goods in four interest-free instalments, while receiving the goods immediately. Customers only pay a fee if they miss an automated payment, a transgression that also locks their account until the balance is repaid. Afterpay says this limits bad debts, particularly in a downturn when job security is shaky and household finances are stretched.

Most of Afterpay’s revenue comes from retail merchants, which pay a percentage of the value of each order placed by customers, plus a fixed fee.

Afterpay’s most-recent financial results — covering the six months through December 2019 — showed late fees, which are $US8 in the US and capped at 25 per cent of the original transaction size, accounted for 15 per cent of $US152m in revenue, or 0.7 per cent of the $US3.31bn in goods and services bought on the platform.

Still, the coronavirus pandemic has tested that model. Worries about users’ ability to pay for items led Afterpay to insist on the first instalment upfront, reducing the total repayment time from eight weeks to six.

Christy McKnight, a 31-year-old accountant from Adelaide, Australia, whose husband lost his job as a medical courier in March, gave up her three Visa credit cards in favour of buy now, pay later.

“Every time I made a transaction, I tried to work out a payment plan and set reminders in my phone to pay it,” Ms McKnight said of her credit cards. “But we were finding that some purchases were just slipping through the cracks.”

Having tested Afterpay on a friend’s recommendation, Ms McKnight now uses it to stagger payments for items, including food for the family’s rescue animals.

In a UBS survey of 1000 Australian consumers in May, one in five respondents said they wanted fewer credit cards. Of those, 13 per cent cited buy now, pay later as the reason.

Paul Becher, a 66-year-old retired pharmacist from NSW, said the 29 per cent interest rate on his credit card was the primary reason he switched.

Analysts had expected buy now, pay later providers to struggle in an economic slowdown. So far, the opposite appears to have happened.

By June 30, Afterpay had 5.6 million active US users, more than half of its global customer base, as lockdowns, lay-offs and store closures pushed shoppers to buy online. “It’s not over-complicated,” Mr Molnar said. “We’re trying to build an economy where everyone wins.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout