In a secret game of prisoner swaps, Putin has held most of the cards

Over six years, the Russian leader stockpiled American detainees, enhancing his bargaining position and thwarting backchannel efforts by Trump and Biden to bring citizens home.

There were no aides and no note-takers in the Oval Office — just President Biden and his German guest.

Chancellor Olaf Scholz came on such short notice that the only plane he could book, a small Airbus 321, had to refuel in Iceland. Russia’s war in Ukraine and the fighting in Gaza dominated the 90-minute meeting.

There was one last secret item on the agenda: Were Germany and America willing to conduct one of the most complex prisoner trades with the Kremlin since the Cold War?

Washington wanted Vladimir Putin to send home two Americans it deemed unlawfully jailed in Russia, former Marine Paul Whelan and Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, who will mark a year in captivity on Friday. Putin wanted Berlin to release Vadim Krasikov, a Russian hit man serving a life sentence in Germany for murder.

It would be a tough thing for the U.S. ally to deliver, but perhaps it could be sold to the German public if Russia agreed to free its most prominent dissident, Alexei Navalny, who was imprisoned in an Arctic gulag.

Both administrations agreed to explore the idea further.

The White House never had a chance to make a formal proposal to Moscow. Word of the discussions reached the Kremlin via a private intermediary, according to people familiar with the matter. On Feb. 16, one week after the Oval Office meeting, Navalny died suddenly of unknown causes.

“Such is life,” the Russian president told reporters the night after his re-election.

It was the most shocking of a series of setbacks in secret prisoner talks between Washington and Moscow that have now bedevilled two U.S. presidencies.

America once had only one prisoner it considered wrongfully jailed in Russia, the 54-year-old Whelan. But through nearly six years of intense and combative negotiations, Putin has run up the score, stockpiling his prisons with Americans to swap for the very few Russians abroad he cares to bring back.

Both Presidents Biden and Trump found themselves facing the crude asymmetry between the U.S. and Russia, whose leader of a quarter-century can order foreigners plucked from their hotel rooms and sentenced to decades on spurious charges.

Putin, whom Biden called “a butcher,” hasn’t been a normal negotiating partner. After news of Navalny’s sudden death interrupted an annual lunch among chiefs of the leading Western security agencies, several attendees immediately wondered if the Russian ruler had ordered a hit. Weeks later, the U.S. hasn’t offered a public assessment of how he died, while Russia has cited only “natural causes.” At the same time, America has been an easy mark, polarised by its culture wars and susceptible to the power of celebrity-driven campaigns that levelled a pressure on the White House never felt by the Kremlin.

The Biden administration came into office determined to craft a consistent approach to prisoner talks — only to be knocked off course by viral outrage when Russia jailed Olympic basketball champion Brittney Griner. As her representatives lobbied the president to free her, if necessary by trading notorious Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout, the Justice Department was concerned such a deal would make it harder to free Whelan and encourage Putin to grab more Americans.

The unreported story of this escalating hostage crisis takes place in clandestine meetings in hotels in neutral capitals booked under false names. The Journal spoke to dozens of current or former U.S., European, Middle Eastern and Russian officials, including individuals directly involved in negotiations. It also reviewed court records and interviewed former prisoners, their families and the people who worked as their backchannel representatives.

The drama features walk-on roles by Hillary Clinton, media personality Tucker Carlson and former New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson, who became involved in the negotiations only to die before Whelan, now closing in on his 2,000th day in prison, could come home.

As of today, the U.S. doesn’t have any Russians in its prison system of the category the Kremlin wants in return for the Americans it has jailed. Washington has been reduced to hoping foreign governments might be willing to trade Russians they hold on espionage or murder charges.

“Putin will take more and more Americans,” said Fiona Hill, who sat across the table from Russia’s president as the top Russia adviser for President Trump. “He has figured out he can exploit our domestic preoccupations and anxieties.”

‘I’m a Marine, I’m tough’

The first time the name “Paul Whelan” landed in the American embassy in Moscow, nobody knew who he was — just that he had been grabbed in a raid on his hotel room during the Christmas holidays of 2018.

In the compound’s safe room, combed daily for surveillance equipment, Ambassador Jon Huntsman was asking the CIA station chief the same question he’d asked other diplomatic staff: Who was this Michigan bachelor, repeatedly travelling to Moscow as a tourist on an ordinary visa?

The station chief was as befuddled as the ambassador, and replied that Whelan wasn’t working for the CIA. The two contacted the White House, where officials determined he’d been set up.

Held in Moscow’s infamous Lefortovo Prison, Whelan told his lawyer he’d been handed a thumbdrive by a friend, then almost immediately arrested by agents of Russia’s Federal Security Service, or FSB. One of them had passed on a reassuring message: You’ll be traded.

Days later, Huntsman arrived to meet him. Whelan was being kept in a complex of roughly 9-by-12-foot cells where lights were turned brighter through the night. Inmates’ sole windows were a slice of translucent glass, so high above eye level that when morning broke, they could only see the gray Moscow sky.

“I’m a Marine, I’m tough,” Whelan told the ambassador. “I can get through this.” Days later, Huntsman bypassed Russia’s foreign ministry to talk directly to Yuri Ushakov, Putin’s chief foreign-policy adviser. With a direct line to Putin, Ushakov could get things done.

Their meeting, in an office next to the Kremlin, was to the point. A Russian activist named Maria Butina had pleaded guilty two weeks before Whelan’s arrest to being part of a conspiracy to influence U.S. politics by becoming involved with conservative groups including the National Rifle Association at the direction of a top official from Russia’s central bank. Russia would be willing to trade her for Whelan. Or it could trade him for a pilot, Konstantin Yaroshenko, sentenced to 20 years for drug smuggling.

“Put a deal on the table and let’s talk,” said Ushakov, who would interrupt meetings to take a call from the president he called “the boss.” There was another prisoner the Kremlin wanted more: Viktor Bout, the Russian arms trafficker loosely fictionalised by Nicolas Cage in the blockbuster “Lord of War.” America’s Drug Enforcement Administration had busted him in Thailand in a 2008 sting operation. Russian diplomats had ritualistically invoked Bout in almost every meeting since, calling him a victim of America’s overreach as a global policeman.

Yaroshenko, grabbed by the DEA in Liberia in 2010, was another American kidnapping on foreign soil, they insisted. Their complaints fell flat with the Obama administration and with Trump.

Huntsman headed to the White House and pressed Trump for a quick deal. “We’ve got to get this done,” the president said.

But Trump sounded a more sceptical tone to Russia specialists in his administration. The president and his national security team feared Putin would sense weakness if the U.S. started eagerly petitioning for Whelan’s release.

The proposition of swapping Whelan for Butina or Yaroshenko never gained momentum. Trading Bout sounded so lopsided that Trump’s national security adviser, John Bolton, dismissed it outright: “There’s no way we’re going to agree to this,” he said he told his staff.

In April 2019, the U.S. lost a card in its hand: A federal judge sentenced Butina to just 18 months in prison. Anatoly Antonov, Russia’s ambassador to Washington, teased U.S. officials that the short sentence had made it easy: Rather than trade Butina, Moscow was now inclined to let her jail time run out.

In August, the score shifted again. Police in Russia arrested another former Marine, Trevor Reed, during a drunken night out with his Russian girlfriend. They had been preparing to release him when two counterintelligence officers walked into the station. Reed, who had served at Camp David when Biden was vice president, found himself facing a nine-year sentence for assaulting a police officer. He denied the charge and said Russian law enforcement provided no credible evidence. The State Department declared him wrongfully detained.

The next month, the House of Representatives began an impeachment inquiry into President Trump’s dealings with Ukraine, removing any political room for swapping prisoners with the Kremlin. “Everything involving Russia basically became radioactive,” one senior official said. In October, Huntsman, the ambassador who had championed Whelan’s cause, resigned.

The best the U.S. could do was a complex exchange of medical care, partially arranged by former Gov. Richardson, who, over the course of nearly a year, got the Justice Department to persuade the warden of Yaroshenko’s federal penitentiary to permit an outside dentist to treat the inmate’s toothache.

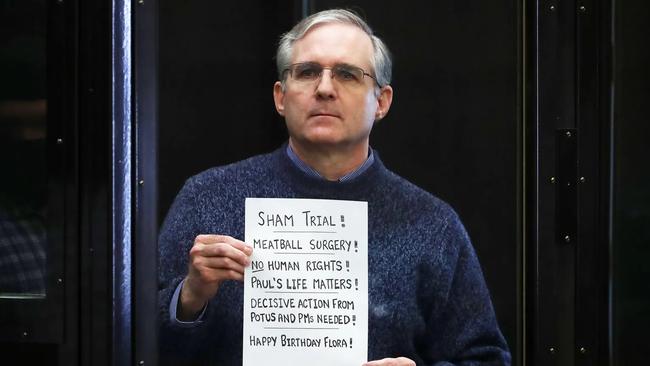

The Kremlin allowed Whelan to see a hernia specialist at a Moscow clinic. Richardson hoped this was building momentum, but in June 2020, a Moscow judge handed Whelan a 16-year sentence. Standing in a glass defendants’ cage and struggling to understand the untranslated Russian, Whelan held up a handwritten note: “SHAM TRIAL!”

Days in IK-17, his new home — a maze of low-slung cell blocks wreathed in razor wire some 300 miles east of Moscow began with the Russian national anthem blaring from tinny loudspeakers, its melody the same as in Soviet times. On the prison floor, Whelan was ordered to stitch pants and coats in a sea of inmates in black uniforms huddled over sewing desks for Technoavia, Russia’s industrial-clothing corporation. Food was scarce and fights were frequent in the labour camp sardonically nicknamed “Fashion Colony.”

When the new U.S. ambassador, John Sullivan, visited him, Whelan was eager to share historical trivia on the prison: It had once held German prisoners of war during its days as a Stalinist gulag. Whelan was keeping a small notebook where he meticulously recorded the slights prison guards meted out to him.

Bout meanwhile, was teaching yoga to inmates in a medium-security Illinois prison. In the mornings, he read The Wall Street Journal, English being one of at least five languages he spoke — six, counting Esperanto. At times, he dreamt about once again tasting fresh garlic and grapes. Frequent visits from Russian diplomats stopped after Washington restricted their movements, but there was hope for Bout, relayed to him in regular phone calls: In all likelihood, he would be traded for Whelan.

That idea was going nowhere inside the Trump White House. New national security adviser Robert O’Brien vowed there would be “no more ransoms.” Instead he tried to shake Whelan and Reed free at the end of a meeting with Putin’s most important official, national security chief and former FSB director Nikolai Patrushev.

The two led delegations to Geneva, barely five weeks before the 2020 election, to negotiate an extension to a nuclear arms control treaty. Russia also wanted to restart conversations on cybersecurity and counter-terrorism. In return, O’Brien asked, could Russia release Whelan and Reed as a gesture of goodwill?

Patrushev offered a loose handshake agreement O’Brien understood as a yes, a fleeting diplomatic win the same day the campaigning president Trump was hospitalised with Covid-19. The State Department was sceptical Patrushev had committed Russia to anything more conclusive than a maybe.

A month later, Trump lost re-election. In his final days in office, O’Brien pinged the Russians again, but they never responded.

“We were aware the Russians were saying nyet. And everything gets frozen, ” one official said.

The Backchannel

Six months later, America’s new president met Putin in a mansion by Lake Geneva, the choreography echoing the city’s famous Reagan-Gorbachev peace summit. Biden wanted a “stable and predictable relationship with Russia,” and agreed to establish a backchannel to discuss prisoner exchanges.

Russian and U.S. intelligence officials arrived for the first backchannel talks at a European hotel, where a conference room had been booked to disguise its true purpose. The U.S. delegation had come reluctantly, leaving phones behind, wary of the prisoner trades they were sent to explore.

The interlocutor studying the Americans from across the table suggested Russia’s appetite for a deal was souring. When it came to Whelan, Russia had a grim new demand: a spy for a spy. If Washington wanted Moscow to free an American convicted in a Russian court of espionage, the U.S. would have to secure the release of a Russian sentenced for an equivalent crime. And the U.S., he added, didn’t have such a convict anywhere in its prison system.

There was, however, one Russian that Putin was starting to ask about: Vadim Krasikov, the former FSB officer serving a murder sentence in Germany. The two were so close the hit man had once bragged about passing time with the president at an elite military training facility: Putin, the erstwhile chief of the FSB, “shoots well,” he’d told friends.

The price for Whelan, after two years in jail, was ratcheting up again. In the weeks that followed, U.S. officials watched as police at Russian airports and elsewhere began scooping up more Americans.

In August, customs officers arrested Marc Fogel, a history teacher at the Moscow high school U.S. Embassy children attend, for carrying less than an ounce of medical marijuana.

David Barnes flew to Russia to find his two sons his ex-wife had taken there, only to be sentenced to 21 years for child abuse charges that he denied and which Texas authorities didn’t find evidence to support. Around the same time, Sarah Krivanek, an American teaching English in Russia was arrested for assault after injuring the male Russian roommate she said had been drunkenly beating her.

None of those cases registered with the American public or with officials — Krivanek says no diplomat ever visited her in jail.

But on Feb. 17, Russian customs agents finally seized someone whose ordeal would resonate.

A basketball star

The authorities at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport had installed three new colour security cameras, perfectly aligned to record cinematic details as Brittney Griner, a two-time basketball Olympic gold medallist, lifted her black rucksack onto a customs table, en route to play with her off-season team UMMC Ekaterinburg. Inside were vape cartridges containing less than a gram of medically prescribed hash oil, illegal in Russia.

News of her arrest became fodder for America’s gathering culture wars: a Black lesbian sports star had been imprisoned by a regime with draconian laws on LGBTQ rights. In the ensuing months, Hollywood and sports celebrities including LeBron James, Kerry Washington and Amy Schumer joined an exploding social media campaign: #WeAreBG.

“Brittney Griner is Trapped and Alone,” read an opinion headline in the New York Times. “Where’s Your Outrage?” While other Americans had struggled to get government attention, the crash team including executives and sports agents working to free Griner could immediately reach the heart of the White House; one had served in the Clinton administration with Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Russian officials realised they had leverage and floated a possible deal: Bout and Yaroshenko for Griner and Trevor Reed, the former White House Marine who had served at Camp David during Biden’s vice presidency. Biden was also under pressure to free Reed: “Trevor had been willing to die for you,” his father, Joey Reed, told the president during a meeting in March.

Joey Reed says his son’s yearslong detention left him shocked at the inability of the U.S. government, under both parties, to negotiate with Moscow: “I don’t think they generally know how to work these kinds of deals,” he said. Putin, he added, has managed to outfox Washington for 24 years: “They know our government better than we know our government.” Biden approved an exchange of Yaroshenko for Reed. On April 27, 2022, the former Marine was flown to a Turkish airport. As he walked out onto the tarmac, and into an American jet, he asked the U.S. delegation escorting him on board: “Where’s Paul?” Whelan, still sewing coats in IK-17 prison, had become the subject of a difficult moral calculus. The U.S. wanted to trade Bout for both Griner and Whelan, arguing the world’s most famous gunrunner was surely worth a basketball centre caught with hash oil and an obscure former Marine. Russia, watching the celebrity-studded campaign to free Griner, proposed to trade both the sports star and Whelan for Krasikov.

U.S. officials protested. The convicted murderer was in a German prison, but the Russians were unmoved. Tell Germany to release Krasikov, the Russians suggested.

Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security adviser, notified his German counterpart of the Russian proposal, but the U.S. didn’t submit a formal request for Krasikov. The CIA sent a query down to its station chief in Berlin — who responded that it wouldn’t even be worth asking. For months, the U.S. and Russia waged a stare-down, the Kremlin hoping the U.S. would deliver Krasikov, and the White House hoping to exchange two prisoners for one.

On Sept. 16, Griner’s wife and agent met Biden in the White House and communicated a plea: Don’t let the negotiations needlessly drag out if there is a narrower deal — either for Griner or Whelan — to be had. The president met Whelan’s sister Elizabeth the same day.

The U.S. tried offering Bout for Whelan — hoping to then trade another Russian convicted of a lesser charge for the celebrity athlete — but Moscow stuck to its guns. For Griner, Bout. And if the U.S. wanted Whelan, they could discuss a trade involving Krasikov.

The Whelan family could feel the tide turning against them once more. “Does this mean he is going to be left behind yet again?” his sister Elizabeth had said to The Detroit News.

Justice Department officials were concerned: Trading Griner for Bout would make it harder to free Whelan, they argued, because there were no other inmates left in U.S. prisons that Russia wanted, plus it could make other countries reluctant to extradite criminals to America. The president overrode internal objections. The State Department dispatched an official to tell the Whelan family that Biden had agreed to exchange Bout to bring Griner home.

“Sadly, for totally illegitimate reasons, Russia is treating Paul’s case differently than Brittney’s,” Biden told reporters, after calling the Whelans.

To retrieve Griner, the State Department chartered a private medical jet with trauma specialists on hand to bring her back to the U.S., where she was later honoured at the White House.

That same day, the State Department put Krivanek — whose sentence for assaulting her abusive roommate had ended — on a commercial flight, and told her she would have to repay nearly $4,000 in travelling expenses. She had been assaulted in a co-ed prison, she said, her knee and two cervical spine discs fractured, injuries treated when a friend met her at the airport and drove straight to a local emergency room.

Watching from afar, Trump criticised the deal on his social-networking site, TruthSocial. “I would have gotten Paul out,” he wrote.

It was the first time the Whelan family ever saw Trump publicly mention Paul’s name.

The journalist

Putin still didn’t have his hit man back.

Just under two weeks after Griner’s release, the Russian president delivered a video speech to the FSB, admonishing them to find more spies: “You need to significantly improve your work,” he told FSB top brass assembled to celebrate Security Agency Workers’ Day, a Russian holiday.

By the new year, U.S. officials had noticed an uptick in surveillance toward the few Americans still in Russia. Evan Gershkovich had been followed on reporting trips in Moscow and western Russia.

On March 29, he was on another reporting trip, waiting at a steakhouse in Yekaterinburg, when masked agents barged in.

Gershkovich was charged with espionage and jailed alone in a Lefortovo prison cell, prompting a worldwide outcry. The State Department within weeks deemed him unlawfully detained and Biden pledged to push for his freedom.

Putin now had two Americans spuriously classified as spies.

When the news reached Whelan in IK-17, it took him weeks to stabilise. He seemed “rattled like never before” and afraid he’d be overlooked for a third time, his family wrote in an online statement.

Months passed with little movement forward in the negotiations. Weeks after Gershkovich’s arrest, the U.S. offered five people, including cybercriminals, a bid it hoped would open new options to return Gershkovich and Whelan without freeing Krasikov. The Russians waited.

From his cell in Lefortovo, Gershkovich was writing letters to friends and family, asking them to deliver flowers to loved ones and to send him obscure Russian literature.

A more ambitious transnational effort to free them had begun to take shape, initially spearheaded by an unexpected source: Hillary Clinton.

The former secretary of state had accepted a proposal from Christo Grozev, a friend and associate of Navalny, to lobby the White House to include the imprisoned Russian opposition leader in negotiations, handing the Russians Krasikov in exchange.

Navalny’s wife, Yulia Navalnaya, had been approaching German officials informally, but the government was divided. Foreign minister Annalena Baerbock opposed any deal involving Krasikov, who had gunned down a perceived enemy of the Kremlin in a Berlin park in broad daylight.

And yet Navalny was such a popular figure in Germany that when he was poisoned with the nerve agent Novichok in 2020, then-Chancellor Angela Merkel helped arrange for him to be airlifted to Berlin, where doctors saved his life. Scholz, the current chancellor, visited him during his recovery and has spoken about how impressed he was with Navalny’s courage and moral strength.

Spokespeople for Navalny and the German government declined to comment. Putin meanwhile, was hinting strongly that he would be open to an exchange that included Gershkovich.

In February, former Fox News host Tucker Carlson arrived in Moscow to interview the Russian leader. Beforehand, Carlson advised the president’s aides that he planned to press Putin to release Gershkovich then and there, so he could personally bring him back to the U.S. An official close to Putin said it would be a “great idea” and could generate a positive response, Carlson told the Journal.

When it came time to spring the question, Putin demurred, although he suggested Gershkovich could be traded for an unnamed prisoner who fit Krasikov’s profile. The Russian leader left Carlson with the sense that he was ambivalent. “Putin basically acknowledged that Gershkovich was held hostage, and my sense was that he was embarrassed about it,” Carlson said.

Momentum appeared to be growing but there was still no final U.S.-German agreement nor any proposal to the Russians. Seven days after Biden met Scholz, Navalny’s closest aides and his wife Yulia arrived at the global gathering of security officials in Munich, where they hoped negotiations could soon reach a breakthrough.

It was not to be. Hours after hearing her husband had died in prison, a tearful Navalnaya held an impromptu speech declaring, “This regime and Vladimir Putin should be held personally responsible.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout