Tolstoy and chess keep Evan Gershkovich’s spirits up in gloom of Stalin’s prison

After almost a year behind bars in Russia, in almost total isolation, the ‘vibrant, chatty’ Evan Gershkovich is holding his own among the ghosts in grim Lefortovo.

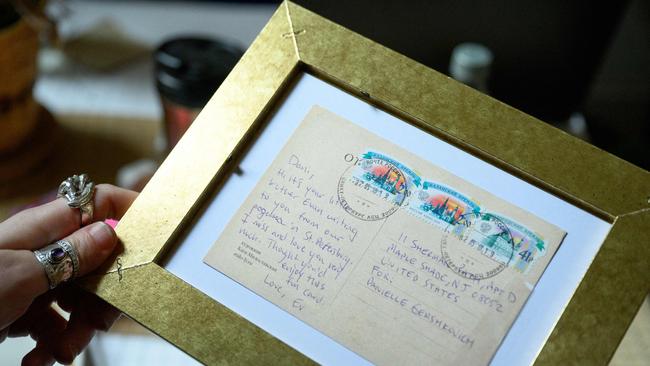

He writes letters, plays chess and does push-ups. In his Russian jail, Evan Gershkovich, a young American journalist, is allowed to watch state television, take one shower a week and talk to lawyers. But what helps him most to while away the time is a well-stocked prison library.

He started with War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy’s monumental drama set in the Napoleonic Wars. Now, as he nears a year in detention on spying charges, he has begun working his way through communist-era classics.

One of them is The Young Guard, a 1946 novel by Alexander Fadeyev about a Soviet anti-German wartime resistance group that operated in eastern Ukraine.

“It’s awful,” Gershkovich, 32, wrote of the book in a letter to a British friend. “But I wanted to understand why my current landlords got so worked up over the Donbas [in eastern Ukraine]. Haven’t worked it out yet.”

Built in the late 19th century, Lefortovo prison has a dark history. It is where Joseph Stalin locked up countless “enemies of the state” in the Great Terror of the 1930s. Many were executed.

The prison is run by the FSB, a successor of Stalin’s secret police and of the KGB, in which President Putin began his career before taking power in 2000. Since then he has outlasted six British prime ministers and four US presidents, reshaping Russia in his image while spreading alarm in the West with his talk of readiness for nuclear war.

Unchallenged in this weekend’s sham election, Putin is on course to draw level with Stalin as Russia’s longest-serving leader if he manages to hold power for another six years.

For some critics, his cruelty to enemies and prisoners is also evocative of Stalin: the unexplained death of Alexei Navalny, the opposition leader, in an Arctic prison camp on February 16 came after a bungled effort to kill him with poison in Siberia in 2020. Last week Leonid Volkov, a Navalny lieutenant living in exile in Lithuania, suffered a brutal assault with hammer and tear gas a day after he wrote on social media: “Putin killed Navalny and many more before that.”

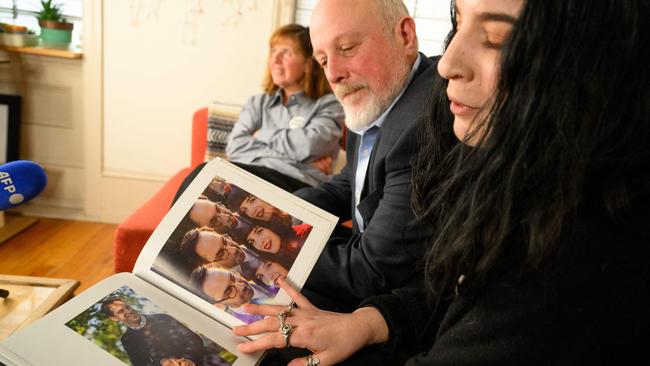

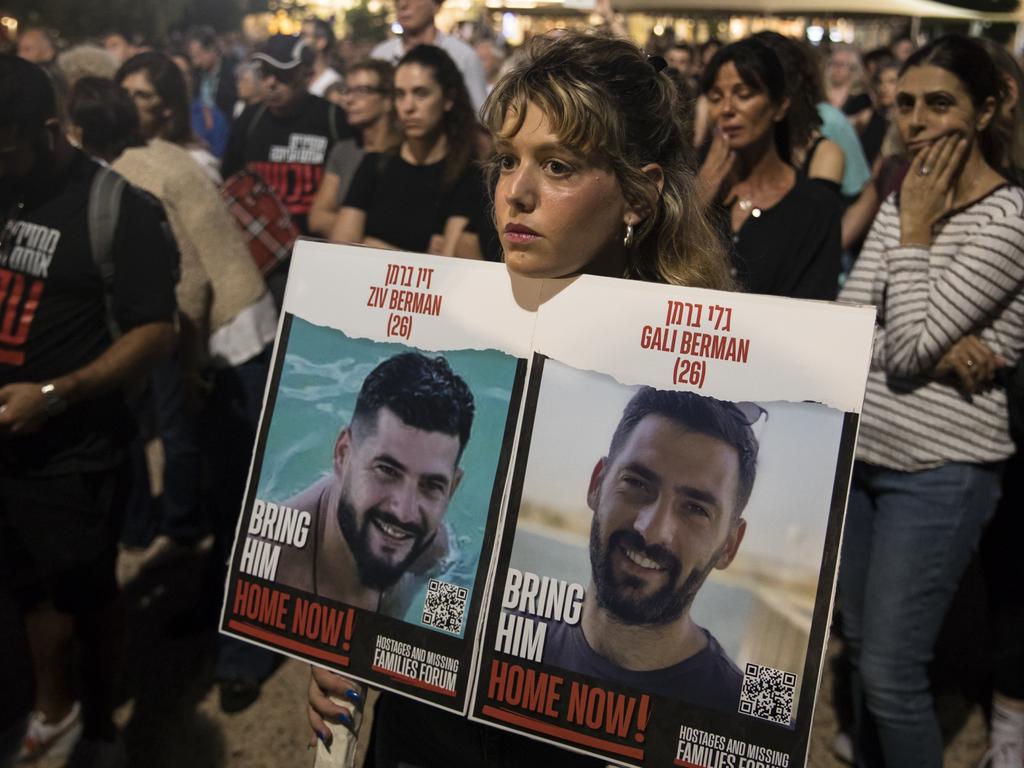

Gershkovich’s family, friends and supporters hope he may be freed soon but have suffered disappointment: Navalny’s death was reported to have sabotaged an agreement under which he, Gershkovich and Paul Whelan, a former US marine also being held on dubious charges in Russia, would have been freed in exchange for Vadim Krasikov, an FSB assassin jailed in Germany for the murder of a Chechen dissident in Berlin in 2019.

“That was a real gut-punch,” said Eliot Brown, who misses the “vibrant, chatty, gossipy, fun guy” with whom he became friends when they met a few years ago in the London offices of The Wall Street Journal. He hopes a new deal will be agreed, even if the Germans are believed to be reluctant to release a Russian killer if they cannot have Navalny in return.

Evan on the cover of Time

— Eliot Brown (@eliotwb) March 7, 2024

FREE EVAN

â¤ï¸â¤ï¸â¤ï¸â¤ï¸â¤ï¸https://t.co/U6TI97YQsPpic.twitter.com/HzF2xGRlzU

Gershkovich, who grew up in New Jersey, the son of Jewish emigres from the Soviet Union, was on a reporting mission in the Urals when he was arrested on March 29 last year on spying charges that are vehemently denied by him and his employer, The Wall Street Journal. He has kept up his spirits, according to Emma Tucker, the newspaper’s editor in New York. “The first letter I got back from him he managed to make me laugh out loud,” she recalled. “That takes some doing, to make you laugh from Lefortovo prison.”

The pale-yellow pre-trial detention centre in eastern Moscow has a fearsome reputation. Tattered carpets cover the corridors, helping to muffle sound. The ghost of Lavrenti Beria, Stalin’s security chief, is said to stalk them: in the 1930s this was a place of horror, where the dictator’s executioners tortured and shot dead an unknown number of victims, using tractors to drown out the noise in the basement.

Prisoners are kept in relative isolation. But Gershkovich is in illustrious company: former inmates include the Soviet dissidents Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Natan Sharansky. The Russian intelligence officers Alexander Litvinenko and Sergei Skripal, both later poisoned in the UK, were also jailed there.

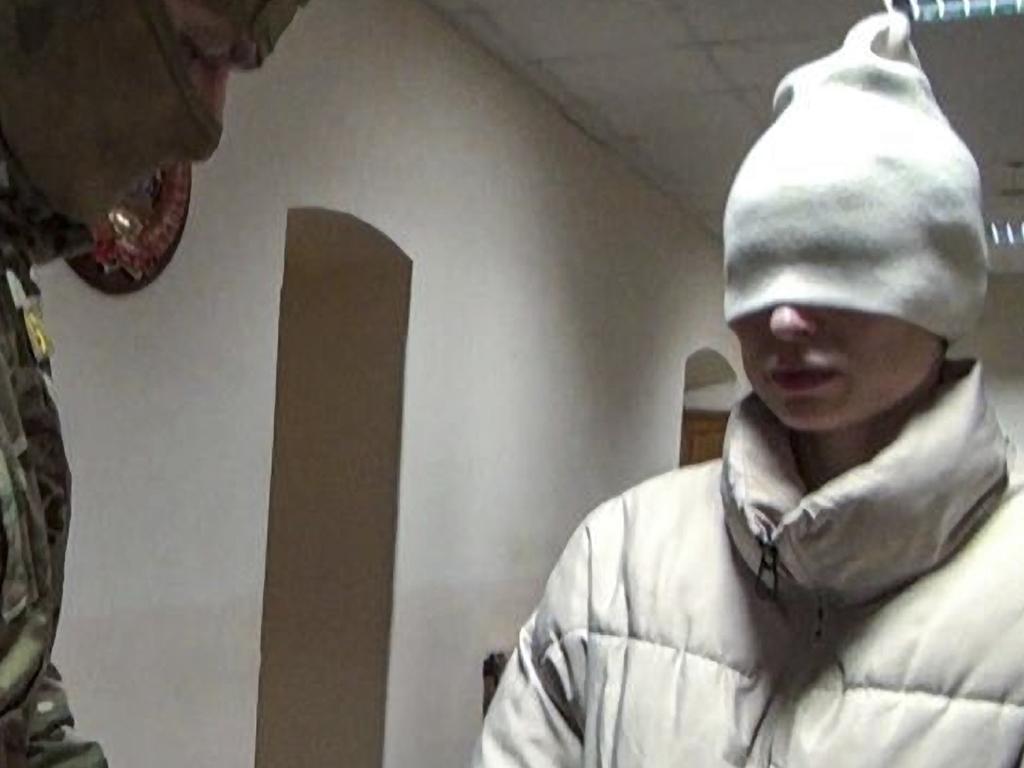

In spite of repeated appeals, Gershkovich’s detention has been extended repeatedly as he awaits a trial said to be imminent. “It’s weird and unpleasant how it’s become a new normal,” said Oliver Farrimond, who became friends with Gershkovich playing five-a-side football in London. “It’s a real jolt when you don’t think about it for a bit and something happens and you see pictures of him being bundled in and out of court in a Perspex cage,” he added. “One of our football team joked that the Russians had taken his last few years of hair - that was a tough crack.”

Gershkovich is allowed an hour a day outside his cell, usually in one of the small courtyards on the prison roof where he walks alone or with his cellmate under a mesh of iron bars - but never getting the chance to mingle with the wider population of inmates.

New arrivals are kept in complete isolation for two weeks, then allotted one or two cellmates but will never meet the other prisoners.

In the cells, a light that shines during the day gets brighter at night. Translucent windows a foot wide and at eye level allow inmates a view of only the Moscow sky. Most cells have two steel-framed beds with foam mattresses, a stainless steel lavatory and a TV. Every few minutes a guard looks through a circular window on the door.

Prisoners are awoken at 6am. They can be called for hours of questioning at any time, marched to the second floor of an adjacent building and a row of interrogation rooms.

As a high-profile American inmate, Gershkovich may be spared some of the worst conditions. He celebrated New Year’s Eve with a few mandarins he managed to buy in a prison shop. When he turned up in court for one of his hearings months ago, the guards allowed him to chat for a minute through the bars of his cage with his parents, Ella and Mikhail. Friends and supporters are able to send him packages of food and clothes.

Some friends worry how the gregarious Gershkovich might cope with isolation until his trial. After sentencing he will be sent to a prison where he is allowed visitors. “He can talk to his lawyers and write letters but Lefortovo is not like prisons where you are all in a canteen for lunch,” said Polina Ivanova, a friend who reports on Russia for the Financial Times. “Your meals are brought to you in your cell, you have only your cellmate for company most of the time.”

Tucker said: “The US government is working hard to get Evan and Paul Whelan back as soon as possible. We as a newsroom are doing everything possible. It’s an outrage that Evan is in prison.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout