The daunting task facing Alexei Navalny’s widow Yulia

Yulia Navalnaya will need to cultivate domestic support to become a potent political figure; harder still, she’ll have to avoid being shot, poisoned, strangled or committing an imaginative suicide.

After Alexei Navalny recovered from poisoning in 2020, his wife Yulia Navalnaya was asked whether her husband should give up his role as Russia’s most prominent opposition figure.

“No,” she said, without pause. “I fully support Alexei’s work, sincerely. Leaving it half done isn’t how you do it.”

When Navalny died in a Russian prison in the Arctic last week, Navalnaya, who had largely stayed in her husband’s shadow, vowed to complete his mission.

With her white-blonde hair and dark-blue dress, Navalnaya cut a ghostly figure at a dimly lit table as she promised to succeed her husband, who for years was subjected to what she called sham trials, prison sentences and poisoning as he vociferously challenged Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Harnessing an outpouring of support and the resources Navalny built through his Anti-Corruption Foundation, or FBK, Navalnaya wants to spearhead renewed efforts to undermine Putin’s rule.

“Putin killed half of me, but my other half won’t give up,” she said in the 9-minute video statement Monday, casting herself in the league of women who fought on in fierce political battles after their husbands died.

But the going will be tough.

The Kremlin’s stringent laws against dissent have enfeebled Russia’s opposition, while Putin’s opponents, including those in exile, have been shot, poisoned or strangled, making the president appear unassailable. Protests, brutally crushed in the wake of Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, are now almost non-existent; even people laying flowers at makeshift memorials are detained.

Navalny, the tall, blue-eyed Kremlin critic, who prison authorities said died last Friday after a walk in the Polar Wolf colony prison camp, had a strength that Moscow found hard to break: his willingness to stay in Russia. After he was poisoned with a nerve agent and airlifted from Siberia to Germany, Navalny returned to Russia in 2021, even though he predicted, correctly, that he would likely be arrested once there.

His widow though is set to continue her husband’s work from abroad, a fraught position from which to gain legitimacy in the intensely patriotic and increasingly closed country.

She will need to build a profile beyond that of being Navalny’s widow, and cultivate domestic support to become a potent political figure, wrote Russian political analyst Tatiana Stanovaya.

“Her success will hinge on her capacity to develop a unique political style, articulate her vision, and assemble a professional team that does not put off potential supporters,” Stanovaya said.

Navalnaya is already taking bold steps, pledging to name those responsible for her husband’s death and show their faces, likely with the help of FBK’s formidable investigators. She is also lobbying the European Union against recognising Russia’s coming presidential elections, which Putin is expected to win virtually unopposed.

“A president who kills his main political opponent is not legitimate by definition,” Navalnaya said earlier this week in Brussels at a meeting of EU foreign ministers, according to a transcript provided by Navalny’s spokeswoman.

On Wednesday, Russian state agency TASS said that Navalny’s mother had filed a lawsuit against authorities, contesting their refusal to hand back her son’s body. A hearing has been scheduled for March 4.

The Biden administration plans to announce on Friday a package of Russia sanctions that responds to Navalny’s death and marks the second anniversary of the invasion of Ukraine, U.S. officials said.

“It will be a substantial package covering a range of different elements of the Russian defence industrial base and sources of revenue for the Russian economy,” national security adviser Jake Sullivan said. The U.S. is working, he said “to continue to impose costs for what Russia has done – for what it’s done to Navalny, for what it’s done to Ukraine, and for the threat that it represents to international peace and security.” Britain has sanctioned six individuals who head up the penal colony where Navalny died “after years of mistreatment by Russian authorities,” the U.K. Foreign Office said.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said earlier this week that Putin hadn’t watched Navalnaya’s address and rejected her allegation that Putin was involved in Navalny’s death.

Navalnaya shot back on social media: “I don’t care how the killer’s press secretary comments on my words.” Rarely granting interviews, Navalnaya and allies of her husband didn’t respond to requests for this article.

“Putin made a big mistake by killing Alexei,” Ivan Zhdanov, the director of FBK, posted on social media. “Now Yulia takes his place. Yulia, who is free. Yulia with noble and just rage.” Despite her political reticence, Navalnaya always played a key, complex, role in her husband’s campaigns. Those close to the family say she helped him choose alliances in the Russian opposition’s ever-changing web of loyalties and feuds. She has been an adviser on his various projects and a consultant during his doomed political campaigns, for mayor of Moscow in 2013, which he lost, and for president of Russia in 2018, when he was prevented from running on technicalities.

“She has always been part of Alexei’s every political campaign,” said Sergei Guriev, a professor at Sciences Po University in Paris, who has been close to the Navalny family. “Alexei has always relied on her advice.”

Navalny said of his wife that her political views were more radical than his. Navalnaya has never spoken out about her husband’s early flirtation with Russian nationalism, but has in the past said she supported him fully.

She can now tap in to the reach and resources of her husband’s formidable opposition operation. Those include a YouTube channel with over six million subscribers that has detailed alleged corruption among Putin’s elite. Her Monday address on the channel garnered over 5 million views in just over a day. An account on X belonging to Navalnaya and created on Monday, already has over 270,000 followers. The account was briefly suspended on Tuesday because, X said, it had been mistakenly flagged.

“What she has right away, thanks to Alexei, is the widest audience of Russian people, in Russia and abroad, more than any other Russian politician, including Putin,” said Konstantin Sonin, an expert on Russian politics at the University of Chicago who personally knew Navalny for 20 years.

Born in 1976 in Moscow to a scientist and civil servant, Navalnaya studied economics and worked in finance. She met Navalny on vacation in Turkey in 1998 and the two married two years later, around the same time Putin came to power in Russia. Their daughter Dasha was born in 2001, a son Zahar followed in 2008.

In contrast to the wives of other politicians in Russia, Navalnaya was beside her husband throughout his rise on the political stage. She accompanied him at protests, stood on the dais with him when he gave the fiery orations that eventually earned him a central place among opposition figures. All the while she shunned a personal role in politics.

When her husband first began coming under arrest and her family’s home was raided in 2013, however, Navalnaya took to the stage in the pouring rain to warn the Kremlin against believing that her husband’s weak spot was his family.

“I came here to say that if anyone in power perceives families as a vulnerable place, then they are mistaken,” she said. “If we have to resist pressure, we will master this science too.”

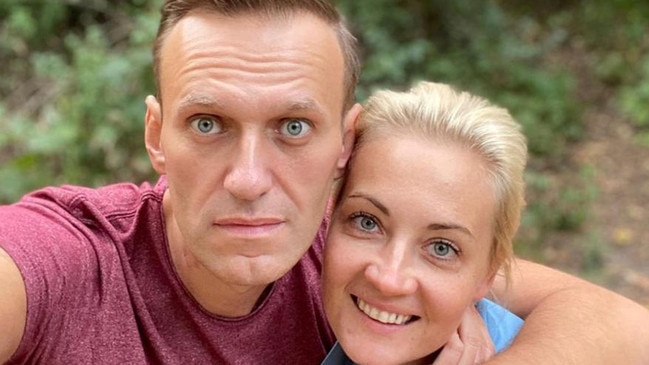

As a couple, the Navalnys weren’t shy about showing affection for one another.

On Valentine’s Day this year, two days before he died, a post on Navalny’s Instagram page showed a photo of them both along with the caption, “I feel that you’re near every second and I love you more and more.”

On work trips, Navalny said publicly, he had strict protocol against female co-workers entering his hotel room even for work meetings to avoid the potential for ‘kompromat,’ or potentially compromising material, that could call his loyalty to his wife into question.

Following her husband’s poisoning in 2020, Navalnaya led the charge to have him evacuated to Germany. At first, according to the couple, Russian hospital staff denied her entry to his room without a marriage certificate and written permission from the patient, who was lying unconscious. But after holding impromptu news conferences outside the hospital and appealing directly to Putin in a letter demanding he allow Navalny’s evacuation, he was released. Her actions likely saved his life.

Scientists in Germany, where he was eventually evacuated, determined that he was poisoned after being exposed to the Soviet-era nerve agent, Novichok. Navalny and FBK investigators eventually tracked down the operative he said poisoned him, finding out that the nerve agent had been smeared inside his underwear while he was visiting supporters in the Siberian city of Tomsk. The Kremlin has denied involvement in the poisoning.

“Yulia, you saved me, and let them put that in all the neurobiology textbooks,” Navalny later wrote on Instagram.

Months later, as both of them flew back to Moscow fully knowing that authorities would detain him at the airport, Navalnaya said in a video from the plane, “Waiter, bring us some vodka, we’re flying home,” a reference from a popular Russian movie. Navalny was detained after the flight.

When he was sentenced to more than two years in prison later that year, the first of several sentences that would amount to some 30 years, Navalny waved to his wife sitting in the courtroom and drew a heart on the glass of the defendant’s cage.

The Wall St Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout