South-East Asian scam compounds ‘test market’ for AI deep-fake technology

Artificial intelligence is transforming the cyberscam landscape and governments are struggling to keep up.

A few months ago, a Hong Kong-based employee of British engineering giant Arup was summoned to a video conference call with his chief financial officer and five other colleagues and told to deposit $38m across numerous bank accounts.

The mid-level finance worker had initially suspected an email from his UK head office flagging the need for a “confidential transaction” was a scam until he joined the video conference and sat face-to-face with his boss.

But his first instincts were right.

The email was a scam, as was the video call in which criminals used cutting-edge “deep fake” technology to impose the faces and mimic the voices of his boss and work colleagues – technology that is now being rolled out in cyber scam operations across Southeast Asia.

Scam-demic: you're the prey

Myanmar scam ties to SE Asia kingpins

A new report outlines a transnational network of businesses built by the Myawaddy Border Guard Force in Myanmar that protects and profits from Chinese criminal syndicates operating online scam centres.

How Asia’s brutal online scam factories reel in Aussies

Chinese-run ‘scam universities’ are training enslaved workers how to fleece Australians out of their life savings. Inside their walls, a modern horror story is unfolding. WARNING: Graphic content

Aussies ‘kept in dark’ over mass scam network

A crime syndicate used scam ads featuring celebrities including Eric Bana to fleece thousands of Australians out of $200m – and ASIC is accused of failing to protect victims.

‘I don’t want her to leave me’: Savings lost to this Facebook scam

A former Victorian real estate agent has been unable to bring himself to tell his wife that he lost $183,000 to scammers. Now he’s speaking out in the hope his story warns others.

ASIC silent on scam which ripped off 34,000 Aussies

One of the biggest scam syndicates to ever attack Australia - which fleeced victims out of more than $200m - is almost invisible on the corporate regulator’s investor alert list.

AI rip-offs from Asia ‘terrifying’

Artificial intelligence is transforming the cyberscam landscape and governments are struggling to keep up.

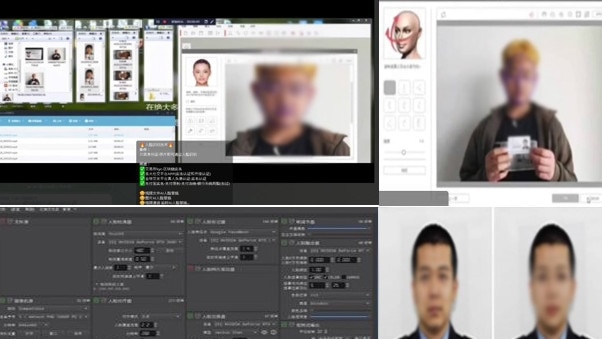

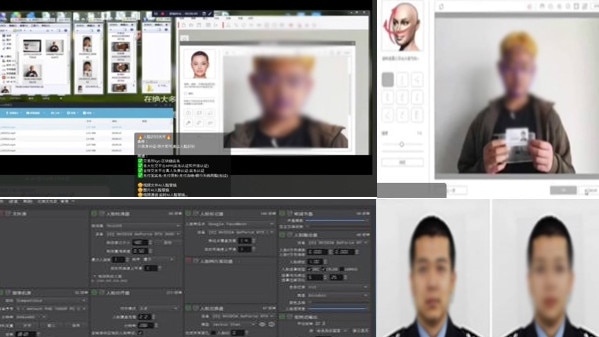

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime says Southeast Asia’s criminal scam enterprises are fast becoming the test market for commercially available artificial intelligence technologies, such as real-time deep fake face-swapping software and chatbots, now being openly marketed to cyber scam bosses on encrypted chat platforms such as Telegram.

Posters advertising deep fake products have even been spotted in phone kiosks across Phnom Penh and Sihanoukville, Cambodia, pointing to the broad accessibility of the technology.

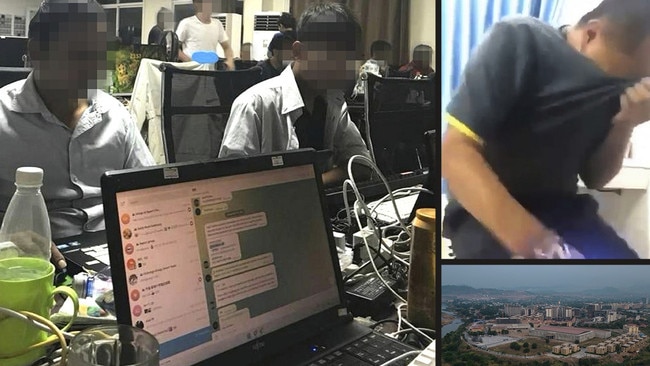

The region is already the global epicentre for Chinese criminal syndicate-run scam compounds running so-called “pig-butchering” scams, in which victims are contacted through social media or text message and lured into fake investment schemes, often involving cryptocurrency trading.

Across Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos and The Philippines, industrial-scale scam compounds are believed to be generating more revenue than the regional drug trade on the backs of tens of thousands of workers caught up in what Interpol calls a “global human trafficking crisis”, subjected to debt bondage, beatings and sexual exploitation.

But the deployment of commercially available AI technologies is now turbocharging cyberfraud, extending the scope and reach of those operations while gradually reducing the need for an enslaved multilingual and computer-literate workforce.

UNODC analyst John Wojcik says Asian crime groups are “quickly evolving into more sophisticated threat actors”, but that those operating out of the Mekong region have become “market leaders” in the multibillion-dollar industry.

As new technologies are developed and refined at light speed, “it is becoming increasingly difficult for governments in the region to keep up”, says Wojcik.

While a year ago AI social engineering technology might have needed a 30-second audio clip of someone’s voice to clone it, that has now been refined down to just two or three seconds.

The first words of your answering message would be sufficient.

Similarly, real-time face-swapping software has vastly improved, with early glitches ironed out.

“The emergence of new deep-fake technology service providers catering to cyberfraud operators in Southeast Asia is particularly concerning amid the wave of impersonation fraud hitting the region,” Wojcik tells The Australian.

“Together with unprecedented access to personal identifiable information through underground data brokers to build profiles of unsuspecting victims, it’s clear that the social engineering capabilities of these transnational criminal groups are increasing fast.”

While the Arup scam is believed to be one of the biggest known deep-fake scams seen so far, the possibilities for the criminal application of such technologies are as frightening as they are endless.

“It’s actually terrifying,” one regional expert told The Australian.

Where most people’s experience of scams now might consist of a few annoying text messages a week or Facebook messages trying to get me to invest in crypto, “in a few years time it is going to be far more sophisticated. Where this is moving to is you won’t be able to tell real from fake,” he says.

“There are 407 illegal online casino compounds in The Philippines alone. These are massive, established sites that look like university campuses. The last one raided had 34 buildings.

“Whole parts of these countries have effectively fallen into the hands of organised crime. It’s a massive problem no one has come to terms with yet.”

A January UNODC report warned AI could now create computer-generated images and voices “virtually indistinguishable from real ones”, allowing scammers to execute “with alarming success” social engineering scams such as investment fraud and pig-butchering, but also sextortion schemes and the impersonation of police and other government officials.

Authorities in Thailand and Vietnam have been grappling with a recent spate of cyber crimes in which scammers have impersonated police officers to extort fines.

Criminals can now also use profile photos harvested from social media to create fake profiles and “masks” that can bypass digital face verification systems, adding to challenges related to money laundering operations.

Kathy Sundstrom, outreach and engagement manager for Australian cyber security agency IDCARE which helps victims of scams and identity theft re-establish identity protections, says even basic AI tech such as ChatGPT has “changed the world for all of us, including cyber criminals”.

“I used to advise people that one of the first red flags to look out for when it comes to receiving fake emails or text messages is the dodgy typos and spelling mistakes. But those days are gone,” she says.

Now she is more inclined to believe the legitimacy of a message if it does include mistakes, which are likely to indicate human error.

“When it comes to receiving incoming text messages, phone calls or emails we need to treat all of them as suspicious upfront and go through checks for multiple red flags, starting with who is sending it to you,” she advises.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout