Rudi* was deep into a 16-hour shift when the bang of a drum echoed across the work room, snapping his attention from his computer screen and the multiple chat streams he was juggling with Australians online. The sound could mean only one thing; someone in this cavernous room of cyber scammers had hooked a big fish – an Australian priest and some of his congregation, as it turned out – and there would be karaoke and barbecue later to celebrate.

Just weeks into what had been sold to him by a friend as a dream digital marketing job in The Philippines, but had quickly turned into a nightmare, the young Indonesian designer jumped to his feet to join the hoots and applause.

There was nothing to be gained by standing out. He had no passport, no money, his phone was monitored, and the scam compound in which he was imprisoned was heavily guarded.

It didn’t take long for Rudi to realise he had been tricked and trafficked into one of Southeast Asia’s many scam factories. But by the time he did, he’d already accrued $5000 in debt to the Colourful and Leap Group that had recruited him.

It was money he would have to repay by scamming others before he could leave, he was told. Money he did not have.

The Australian churchgoers had been fleeced of hundreds of thousands of dollars after their pastor had been romanced into a fake crypto currency trading scheme by a team of scammers operating behind a fake Facebook profile of an Australian woman in one of the most lucrative of all cyber-scams.

Southeast Asia has become the global centre of the “pig butchering”, or romance, scam – so named because targets are “fattened” by a team of scammers who spend weeks or months winning their trust before going in for the “kill”.

Tricked into believing he was making huge profits with the help of a woman he thought he loved, the clergyman had spruiked the scheme to members of his church.

Now their combined life savings had been transferred into crypto currency wallets controlled by the Chinese scam bosses.

“There was a big celebration because our division achieved its target. Everyone was clapping and standing up and really, really making a lot of noise,” Rudi recalls of that day in January 2023 from back in Indonesia where he is now a witness in a Philippines’ trial of mid-level scam bosses charged with cyber fraud and human trafficking.

“The situation was really dark. The most successful scammers would boast about how the people they tricked could no longer afford to send their kids to school, or had lost their house to the bank, and everyone would laugh.

“A lot of people were uncomfortable but couldn’t say bad things about the company.”

As a new recruit Rudi would spend his first week in what he describes as “scam university”, learning about the Australian banking system, Australian culture, how to connect with Australians on Facebook, WhatsApp and dating sites such as Tindr and Bumble. “They told us about Australian bank rules so we could advise people how to take out loans for crypto currency investments, about the behaviour of Australians, Americans, Europeans – that Australians and Americans like to spend money,” he tells The Weekend Australian. “I still thought then they were just introducing the company marketing.”

Later, he was told it was easier to scam Australians with fake crypto currency schemes than Europeans, that Australia’s banking and government regulations were easier to get around.

In Rudi’s compound, brazenly run from a clutch of multistorey buildings inside the Sun Valley special economic zone three hours from Manila and next door to the Clark Air Base, 2000 workers toiled seven days a week to lure Western targets with fake investment schemes.

Online scam activity is now so pervasive it represents one of the world's fastest growing economies with conservative estimates putting its annual earnings at more than $60bn a year.

Australians reported $2.74bn in losses to cyber fraud in 2023, more than $200m of that to romance scams, according to the Australian Consumer & Competition Commission’s latest Targeting Scams report – though fewer than 40 per cent of victims worldwide will report the crime.

The UN Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) says pig butchering run from compounds on Australia’s doorstep may already be generating more revenue than the regional drug trade.

But in Southeast Asia, it is a double-edged crime that exploits two sets of victims.

On one side, tens of thousands of workers caught up in a “global human trafficking crisis”, forced into scam compounds and subjected to “debt bondage, beatings, sexual exploitation, torture, rape, even alleged organ harvesting”, says Interpol.

On the other, many millions of ordinary citizens whose torment may begin with the loss of hard-earned life savings, but can reverberate over many years of self-recrimination at futures destroyed and families torn apart.

The industry’s roots trace back to Beijing’s pre-pandemic crackdown on money laundering in Macau that forced Chinese casino kingpins to search for more permissive operating environments.

They found them in Southeast Asia’s many under-regulated special economic zones, in Myanmar’s lawless autonomous border areas, and in towns like Sihanoukville in Cambodia that had already become magnets for large-scale Chinese investment and organised crime.

Huge casino developments sprouted across northern Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar, where corrupt local powerbrokers and ethnic warlords were happy to take their cut. By 2022, more than 340 were operating across the Mekong region.

When pandemic border closures shut out millions of Chinese gambling tourists, those casinos went online and found a whole new market – all stuck at home, all online and more vulnerable than ever to cyber fraud.

Many casinos had already been dabbling in online gambling – models doing live card dealing on camera, or running online games – but it “exploded during Covid”, says UNODC chief of staff Jeremy Douglas. “You could have your casino in the jungles of Myanmar and have people gambling in Melbourne and Vancouver,” he says. “Those casinos run by criminals, or with significant criminal connections, realised the same technology could be used to run scams and they simply branched out.”

The seeds of Southeast Asia’s “scamdemic” had been sown. All it needed was a vulnerable, computer-literate workforce to power it.

Scam central

Of all the crime parks in Southeast Asia, the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone in northern Laos is surely one of the most extravagant – a confection of grandiose Italianate architecture, Asian glitz and Disney theme park underpinned by a multi-billion-dollar criminal economy.

Yet business seems pitifully slow on a recent Thursday at Kings Romans casino, the gaudy centrepiece of a shadowy enclave inside Laos but controlled by one Chinese gangster tycoon, Zhao Wei, and his Chinese-Australian wife, Guiqin Su.

Much of the casino complex on the banks of the Mekong River – built to resemble a lotus flower – has been shuttered since Covid killed the Chinese tourist trade. Less than 150 gamblers are on the betting floors when The Weekend Australian visited this month.

On the streets outside the casino there are no customers in the restaurants or jewellery shops, none in the 24-hour shopping mall or beauty parlours. A new Disney castle-style development sits empty across the canal, and a night food market is almost entirely populated by Chinese, Asian and African workers.

The new Zhao-built Bokeo International Airport – 5km outside the private militia-manned SEZ perimeter via a gloriously smooth and empty Zhao-funded highway – is shuttered, though it’s barely 7pm. Still, construction is booming in the SEZ, fuelled not by Kings Romans’ blackjack tables but the proceeds of cybercrime, human trafficking, drug smuggling, child prostitution and illegal wildlife trading, the US government alleged in 2018 when it added Zhao, his wife, and an Australian co-director, Eberahim Abbas, to its sanctions list.

The three were also sanctioned by the British government last December for trafficking victims into “online scam farms”, as were several Chinese kingpins and ethnic warlords, in a joint UK, US and Canada announcement that underscores the depth of concern.

The busiest zone in this strange and menacing city appears to be a set of security gates at the fenced perimeter of a compound of multistorey buildings through which a United Nations of workers is checked in and out.

Zhao – a former Macau casino operator with close links to the Chinese Communist Party – has made a show of complying with a recent Beijing crackdown on scam centres targeting Chinese workers and investors.

Last year, signs declaring an amnesty on stun guns, cattle prods and side pistols – the tools of any scam boss’s trade – began appearing in hotel lobbies across the SEZ, where rich Chinese mainlanders drive plate-less luxury vehicles, business is done in Mandarin and Chinese yuan, and Chinese enforcers are everywhere.

Kings Romans may be the Golden Triangle’s central money laundry – the message seemed to be – but it would not be a safe haven for scam compounds.

‘They treat you so bad’

Across the road from the bustling security checkpoint, however, a young African named Ben tells The Weekend Australian the compound houses multiple scam companies, and describes a prison-like environment in which thousands of trafficked workers live and toil.

The fluent Mandarin speaker was one of them until a recent dispute with his bosses culminated in a savage beating. He took his grievance and bruises to the local Chinese-run police station, which ordered his bosses to hand back his passport.

“I didn’t like scamming people and after four months I said I didn’t want to do it anymore. The Chinese treat you so bad. There are no days off. They beat people,” he says as we chat kerbside, attracting unwanted attention from onlookers who inch closer to listen. It is an unnerving place to talk, even before the street is suddenly plunged into darkness by a city-wide power failure.

“Every day people want to leave, and every day new people come in, but none of them know what they’re coming to,” Ben says.

“There are so many Indians and Pakistanis – a big company recruits them. The agency pays money to get them over here and then the company pays the agent and takes all their passports. If you want to leave you have to pay so much money back.”

He insists “scam companies are everywhere here”, dismissing recent joint Laos and Chinese police operations as “show raids”.

Many work out of the sprawling compound across the road, others in discreet multi-storeys organised like layer-cakes of vice, with cyber scams on some floors, call centres, online gambling, and live-streamed sex shows on others.

A grim complex of 13-floor buildings a few streets away has bars on every window, razor-wire fencing and guards at the entrance. At night, workers can be seen pressed against those bars looking down onto Kings Romans’ empty streets.

“This is a very bad place but no one can leave because they don’t have their passports,” says Ben. “You can’t trust anyone here.”

Going global

Yet he has chosen not to leave Kings Romans and instead to try to make a living as a cyber scam recruiter – a job he admits is getting harder as accounts of the industry’s brutality spreads.

That notoriety, and the effect of China’s intermittent crackdowns, has forced scam centres once focused on mainland Chinese to internationalise.

Where earlier only Mandarin-speakers were trafficked into the compounds, now workers are being lured from as far as South America, East Africa and western Europe.

Likewise, the scams themselves are more globalised in outlook, requiring “much stronger international police co-operation”, says Interpol. In the absence of that, a nexus of criminal syndicates and corrupt local agencies in weak legal jurisdictions has helped create what the United States Institute of Peace described in a report this week as the “most powerful criminal network in the modern era”.

“Many countries aren’t even collecting relevant information, much less sharing”, with the exception of China which has massive amounts of intelligence that it is largely keeping to itself, says report author and USIP Myanmar country director Jason Tower.

While China, Thailand, Laos and Myanmar agreed last August to establish a joint police operations centre to tackle cyber scams, sharp geopolitical tensions are getting in the way of badly needed collaboration between Beijing and Western nations such as Australia and the US. The Australian Federal Police agreed to, and then cancelled, an interview with The Weekend Australian on the scam industry, then reneged on an undertaking to provide written answers to a series of questions.

Failure to pool intelligence has allowed scam operators to maintain skeletal operations across multiple countries and move quickly to dodge sporadic crackdowns in an ever-evolving game of whack-a-mole.

Many believe only Beijing has the clout to tackle the scale and reach of Southeast Asia’s “scamdemic” – but only if it is prepared to look beyond its own national interests.

Tower says Big Tech must also shoulder blame for providing the platforms – Facebook, Twitter/X, TikTok, online dating sites and encrypted chat groups such as WhatsApp and Telegram – that allow criminals to not only scam billions of dollars a year from unsuspecting victims, but also to lure workers into cyber slavery.

“In my view, if this is all still happening on an industrial scale despite the checks put in place then we have a problem, right?,” he says, adding the vast majority of trafficked workers responded to false recruitment advertisements on Facebook.

Those working to counter the industrial-scale trafficking, such as Mechelle Moore of the charity Global Alms, are less polite.

“If you don’t have dedicated teams to stop this, then you’re complicit,” she says.

In the absence of effective strategies, horror stories are pouring out from victims at both ends of the “scamdemic”, though few experiences better encapsulate its dual victimisation than that of Anne-Lee*.

Reeling her in

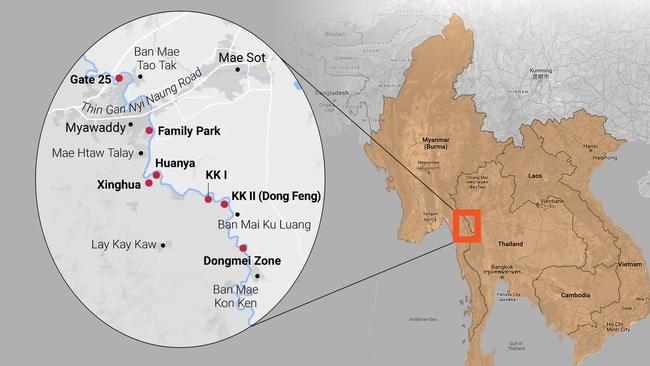

The Asian Australian woman lost more than $750,000 last year to one of the many scam syndicates that line the Myanmar side of the Moei River separating Karen State’s Myawaddy from western Thailand’s Mae Sot.

The deception began in November 2022 with an “accidental” WhatsApp message sent from a Hong Kong-based businessman with interests in Australia.

“He said he was returning from Hong Kong to Melbourne and was arranging to meet a friend for dinner. I told him I didn’t know him, and he explained that he sent the message by mistake. I replied, saying it was OK,” she recalls.

A conversation started, and within days the man – in fact a team of scammers – mentioned he’d hidden money in a crypto account during his divorce, and had used some of the profits to buy gifts for his mother. He sent photos of his purchases.

With his encouragement, Anne-Lee opened an account on what would turn out to be one of tens of millions of fake crypto trading platforms. She invested modestly, made a profit and cashed in.

The confidence trick was designed to reel her in.

“I’d never traded crypto before so I didn’t know what a real trade looks like,” she tells The Weekend Australian. “He kept encouraging me to invest more.”

It was all a ruse, of course. When she finally went to withdraw her money, there were hefty taxes to pay, then a fine to release funds frozen “due to irregularities”. By the time the penny dropped it was too late.

“The funds I lost were meant for building my house,” she says. “My plan was that once the house was built, I could retire. I was almost there, but now I don’t know when I’ll be able to achieve it.”

For most victims that is where scam teams break contact. But, incredibly, it was then that one of Anne-Lee’s scammers reached out for help. The young Malaysian told her he’d been trafficked into a compound in Myawaddy, and forced to scam. He sent videos of his location that The Weekend Australian tracked to the desolate Myawaddy Complex on the banks of the Moei River.

Thai workers on the opposite bank told The Weekend Australian the casino was still open but operating largely online. Local anti-trafficking activists confirmed online scammers had operated there until last year.

Standing on the Thai side – where signs up and down the Moei River warn “Thai people and Foreigner (are) being deceived into illegal working online” – it doesn’t take long to attract the attention of casino security. One walks to the river’s edge to eyeball me.

The same thing happens up and down the narrow river border.

At KK Park, a compound that exploded in size and reach during the pandemic and now hosts six separate parks, boasting restaurants, resorts, casinos, brothels and scam compounds, guards in green-roofed watchtowers train their scopes on me.

Anne-Lee’s Malaysian scammer told her he was beaten, given electric shocks and burned with cigarettes inside the Myawaddy compound where – like Rudi – he was schooled on Australian culture and finance, and made to learn phone scripts.

She says she tries to find comfort in the operation’s sophistication, “telling myself it’s not because I’m stupid; that anyone targeted by them would have been deceived because there’s always a script that fits them perfectly”.

Eventually she agreed to help the Malaysian, after first hiring a private detective to check his story. She contacted his family and helped them transfer $13,000 to his scam bosses to secure his release. The extraordinary gesture was a “welcome distraction” from the torment of having lost her family’s life savings, she says, though even now she is concerned for his safety.

The torture site

Anti-trafficking groups across the region say scam centres have exploded since the pandemic, as has violence against trafficked workers, with some of the most shocking accounts coming out of Myawaddy. Thousands have run for their lives from scam compounds, begged family to pay ransoms, or sent distress calls to embassies, which are issuing warnings across the region about the risks of being trafficked by cybercrime syndicates.

One Mae Sot-based rescuer, who asks not to be named, cites a case in recent months in which two Nepalese women trafficked into the notorious Tai Chang mountain compound were tortured for refusing to work.

“They were made to stand with their hands cuffed above their heads for two days and nights. The Chinese bosses threw water on them and electrocuted them 22 times over 48 hours. They were given no food or water. They could not go to the toilet.”

Their release was eventually negotiated by their embassy through interlocutors with the Myanmar junta-aligned Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA) militia which provides security for Tai Chang.

In some compounds, new workers who underperform are made to run laps of the compound, or do squats in the middle of a scam room, he says. The punishments quickly ramp up.

“You might have to stand and hold a 40kg container of water with your knees bent. If you try to straighten your knees they electrocute you. Sometimes they tie people up in the sun.

“They use wooden clubs with nails in them to beat people and they drag the nail down the skin so they bleed. There is a lot of that.”

Mechelle Moore, who heads Australian anti-trafficking charity Global Alms out of Mae Sot, says she used to be able to see workers being punished inside Myawaddy’s Gate 25 compound from over the Moei River until screens were recently installed.

Moore helps workers escape Myanmar scam compounds, but also to negotiate a Thai legal system that often punishes trafficked victims for having fallen foul of immigration law.

Many are genuine victims, she says, though there are cases where “career scammers” in wage disputes with their bosses have alleged abuses and sought help only to return to the scam compound. On a tour of the fortressed compounds along a 30km stretch of the Myanmar border – in some sections barely 100m from Thailand – she tells The Weekend Australian violence has escalated as Myanmar’s security climate has deteriorated.

“It used to be workers were treated well at the beginning and paid great salaries to incentivise them and slowly they would be scaled back,” she says.

But at the feared Tai Chang compound new recruits are tortured first to “incentivise” them.

“They can be locked in a ‘dark room’ for days, made to drink their own urine, tasered in the dark, beaten with rods. Sometimes they won’t get fed for days,” she says.

“The compounds will pull one person out, brutally beat or torture them in front of others to force others to comply. Everyone is ready to scam after that.”

‘We were really evil’

Under such duress, the exploited can become ruthless exploiters.

Indonesian lawyer Eko Panji says he barely recognises the man he turned into during his seven months trapped inside a Philippines scam compound last year after accepting what he thought was a well-paying job at a Manila hotel.

“If we didn’t meet our scam targets, we’d get shocked with cattle prods. If we dozed off a bit while working, we would be beaten,” he says. “Our victims were mostly over 40 and divorced. We would approach them with the idea of becoming their life partner. Most of them work in government or high-ranking positions.

“I even once scammed an Australian diplomat whose wife had passed away. We played the role of someone who would replace his partner. We indoctrinated him like that. We told him, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll be your partner now’.” Eko says Westerners were easier to win over using the stolen profiles of Balinese women because “they were interested in the exotic aspect, right?”

But he also targeted fellow Indonesians, including a man whose son he continued to scam after his father died in an accident on the way home from mortgaging the family’s land.

“At the time, we didn’t feel pity because we were under pressure too,” he says. “Now we look back and think we were really evil. But my fate was also at stake.”

The Weekend Australian has seen a video of workers being savagely beaten by a scam boss. It was taken inside a Myawaddy compound and smuggled out by a rescued worker. A video taken in another Myawaddy compound in which an underperforming scam worker is handcuffed to an iron bed and given electric shocks was sent to his family with a ransom demand. In a third video three men who fall short of their quotas are made to do squats in the middle of a scam room while a co-worker furtively films their humiliation.

Blue Dragon, an Australian and US government-funded anti-trafficking charity in Vietnam, says many Vietnamese women it has rescued testify to having been passed between scam centres and brothels to make up scam quota shortfalls.

Its Australian founder Michael Brosowski says, the explosion of scam centres has “transformed the human trafficking landscape” in Vietnam. Where before the pandemic most of their rescue missions were to liberate women and girls trafficked into China for forced marriages, “now it’s mostly for scams”.

The consequences

After years of sporadic crackdowns, China is now intensifying pressure on Myanmar, in particular, to take action.

Thailand too announced on Monday it was cutting internet and phone connections to Shwe Kokko city, a special economic zone upstream of Myawaddy billed as the “new Macau” by its Chinese casino and scam compound kingpin She Zhijiang, head of the Yatai International Group and a wanted fugitive in China who was arrested by Thai police in 2022.

Last week, Saw Chit Thu – the junta-aligned commander of the Border Guard Force militia that controls Myawaddy and provides security for crime syndicates there – also announced a change in policy.

Foreign workers inside Myawaddy scam compounds and in Shwe Kokko would have to go by October 31, though he did not order their closure.

“Our main focus is on Chinese telecom scamming operators,” said a spokesman for Saw Chit Thu, who was among those sanctioned last December.

The timing is no coincidence.

Last month the junta and its BGF allies almost lost Myawaddy when key military posts and parts of the city fell to resistance forces.

The junta’s failure to crack down on scam compounds has already cost it dearly. It lost northern Shan state (bordering China’s Yunnan Province) last October to resistance-aligned forces promising to wipe out scam centres targeting mainland Chinese, after Beijing tacitly shifted allegiance from junta proxies there.

In the months since that Operation 1027, more than 40,000 Chinese – among them powerful war lord families but also trafficking victims – have been handed to Chinese police.

Arrest warrants have also been issued for senior Myanmar military and militia figures.

The International Justice Mission, which assists genuinely trafficked scam workers negotiate the legal repercussions of their dilemma, including Rudi, says scam factories flourish in lawless zone where “people can get away with doing crime at scale”.

“But what we have seen in our work is that when consequences are introduced, rates of trafficking and other violations reduce significantly and quite quickly,” says regional vice-president Andrey Sawchenko.

Operation 1027 marked a turning point for Myanmar’s resistance forces which have since seized hundreds of strategic border towns, military posts and trade routes from a junta that has never looked weaker.

AI makes an entry

The impact on Myanmar’s scam industry has – so far – been less momentous though, as pressure mounts, Southeast Asia’s scam lords are again adapting.

The UNODC’s Jeremy Douglas says cyber scamming has become increasingly sophisticated as Artificial Intelligence technologies, including generative AI chatbots, face swapping and real-time translation, reduce the need for an army of multilingual scam workers.

“AI is changing the game because you need fewer people. You can use avatars instead. You don’t necessarily need people who are fluent in languages. You can use deep fake faces and voices,” he says.

“I sat in a briefing recently where AI was able to replicate a voice after a few seconds. That’s the future for this industry.”

A growing “professionalisation” of Southeast Asia’s scam industry is good news for thousands of young workers vulnerable to fraudulent recruitment and trafficking.

But it is a terrifying prospect for law enforcement.

“Some of the most sophisticated scam operations are now operating out of Dubai, including those run by notorious Chinese Triad 14k commander Wan Kuok-koi, better known as Broken Tooth, and the Colorful and Leap Group which swindled the Australian congregation.

The company shifted in May 2023 following a Philippines’ police raid triggered when Rudi called the Indonesian embassy.

For three months he worked 16 hours every day, using fake Facebook and online dating profiles to scam wealthy and vulnerable Westerners, without success.

Sometimes he would collaborate with “models” employed in the compound, who could “video chat” with sceptical targets in studio bedroom, office and lounge room settings, as part of the romance scam.

But the drum never banged for Rudi.

No longer being paid and allowed just one meal a day, he demanded his release, but was instead sent to a building for recalcitrant workers and told to raise the money for his freedom.

He finally made it home last July, though the experience cost him his cafe, his health and eight months of his life.

Still, he keeps in touch with friends from the Sun Valley compound who chose to move with the company to Dubai and say they have greater freedom there than they did in The Philippines.

Life is good, they tell him, and so is the money.

Additional reporting: Dian Septiari

* Not their real names

* An earlier version of this story cited the findings of a report carried on Bloomberg wire that the industry was now the world's third's largest economy which the UN Office of Drugs and Crime has since contested. It also cited Interpol chief Jurgen Stock who told reporters at a Singapore press conference in March that the online scam industry took in up to $US3 trillion annually. Interpol has since clarified that the figure referred to all illicit proceeds of crime channelled through the global financial system annually.

Amanda Hodge is The Australian’s South East Asia correspondent, based in Jakarta. She has lived and worked in Asia since 2009, covering social and political upheaval from Afghanistan to East Timor. She has won a Walkley Award, Lowy Institute media award and UN Peace award.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout