Climate solution may lie beneath our feet

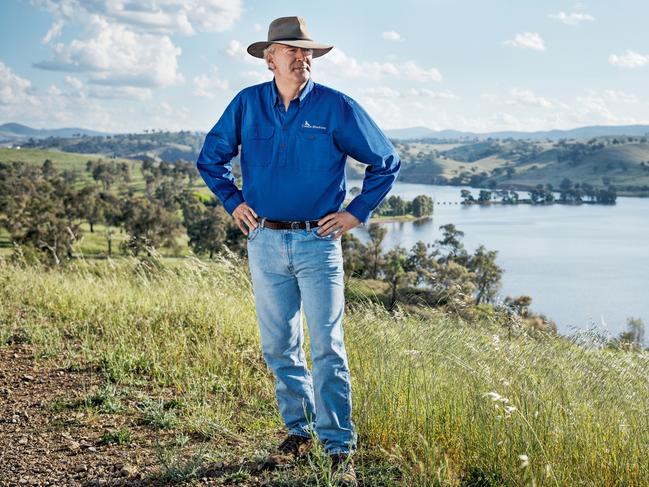

One answer to the global emissions question is right beneath our feet, says newspaper publisher turned commercial cattle farmer Alasdair MacLeod.

It was a conversation back in 2005 on how to better equip the Murdoch family property Cavan that ultimately led to Alasdair MacLeod becoming a leader in the soil carbon movement.

The conversation took place in the middle of the millennium drought and MacLeod, then publisher of The Australian and The Daily Telegraph, was challenged, “If there is a problem, you should fix it”.

MacLeod says the issue was “Cavan was being run in all wrong ways, pushing the place too hard to maximise financial return..”

Sixteen years later and while MacLeod hasn’t stopped the droughts, his focus on natural capital and the importance of efficient farm management has made him something of a pioneer in the soil carbon movement. He recently set the local industry alight with a $500,000 Microsoft deal crediting the carbon created in the soil on his property, Wilmot, in the New England region of NSW.

Sequestration of soil organic carbon is a process that removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and stores it in soil’s vegetable matter. Carbon is at the centre of the interplay between the living, mineral and dead matter.

MacLeod says it is important to stress that the carbon credits were accumulated while the property was being run as a commercial cattle farm.

The relationship between the two holds the key to the work his Macdoch Foundation is doing by sponsoring the Farming for the Future initiative to firstly establish the data showing the links and then laying down the processes to help farmers manage this going forward.

-

“There is a real issue now about what you do with the land: grow carbon or grow beef? In New Zealand domestic carbon prices run up to $60 per tonne and people are planting trees instead of crops or herds.”

— Alasdair MacLeod

-

MacLeod says consultants will suggest, “You have a few paddocks down the back not being used so plant some trees and we can generate carbon credits”.

Soil carbon sequestration, he says, is more part of farm management than a byproduct of running cattle. The Microsoft deal was done in the US in early 2021, but in Australia under the Emissions Reduction Fund, managed by the Clean Energy Regulator, one carbon unit equates to one tonne of carbon and prices in the voluntary market have hit $55 per unit, which is more than double 2020 levels.

THE NEW GREEN ECONOMY

Twiggy’s green ambition put to the test

Andrew Forrest is convinced his ambitious green hydrogen plans are a key plank in the battle against global warming. But can the iron ore billionaire pull off the ultimate pivot?

‘Cats can be herded if there’s a clear goal’: Angus Taylor

The government’s position on climate change is built on respect, says Industry, Energy and Emissions Reduction Minister Angus Taylor.

‘It’s our responsibility to be the adults’: Wikramanayake gets real

In a rare interview the Macquarie Group chief reveals its highly calculated approach to renewables investment and the discussion with her teenagers that crystallised the need to take action.

Is nature really at the centre of the ‘green dream’?

Looking after the land makes sense but in the end, someone has to pay. Good intentions will only go so far.

Rich-listers embrace climate shift

It’s no longer a question of choosing profit over planet. A new generation prioritises impact investing to retrain focus of their family wealth on a climate positive yet lucrative future.

Why climate change is a business opportunity

The transition to carbon neutrality will require trillions. For the financial sector this means not just the opportunity to fund the future, but to profit from it.

Rugby great takes climate fight to Canberra

David Pocock and wife Emma are playing to win with their commitment to turn talk into action on environmental issues.

Billionaire piles pressure on big Aussie polluters

Australia’s enormous resource companies are on notice as a new breed of emboldened financial agitators take an aggressive – and often effective – stance on climate accountability.

Could your car power your house one day?

A reality where the energy stored in your car is plugged in to electrify your home edges ever closer.

Cameron Adams on being a DJ loving climate warrior

Decisive action on climate matters as much as taking democratised design to the world for the co-founder of tech heavy-hitter, Canva.

The Australian names to know in sustainable food and wine

From the man behind Sydney’s fish eatery Saint Peter to a self proclaimed meat-eating vegan, these Australians know a thing or two about sustainable food and wine.

Alan Finkel: ‘Technology is enabled by government’

Now is the moment as government, industry, technology and communities embrace both the urgency and practical reality of emissions reduction.

Climate solution may lie beneath our feet

One answer to the global emissions question is right beneath our feet, says newspaper publisher turned commercial cattle farmer Alasdair MacLeod.

Is this the cure for electric vehicle range anxiety?

Does the idea of electric vehicles give you range anxiety? Car companies have a cure for that, and it’s called a “PHEV”.

Solar plan set to shine

Australia’s appetite for solar continues to surge, driving everything from households and electric vehicles to mining projects seeking a cleaner future.

Six boundary-pushing tech innovations

From a solar-powered outdoor oven to robotic lawnmowers, the latest in green technology sets you up for a future-facing daily life.

Can an office be sexy … and sustainable?

A leading design studio experiments with sustainability by stealth at their innovative – and sexy – Sydney HQ.

The Australian denim brand leading the charge

Start unpicking the fashion industry and the cost to climate is clear. But Queensland’s Outland Denim is determined to break the pattern.

Sky’s the limit: Inside Australia’s greenest buildings

Concern for the environment and employees alike is at the heart of these top four sustainable, and awarded, new commercial spaces. SEE THE PICTURES

Living sustainably is harder than it looks

Two very different lives, one urgent shared challenge: to take concrete steps towards more sustainable daily choices.

Skincare brands put planet before profit

A swath of pioneering skincare brands are setting new low-impact benchmarks in the process.

Solid-state batteries ‘will secure EVs’ future’

For electric vehicles to truly capture the public’s imagination – and wallets – charging certainty and speed is necessary. Enter the solid-state battery.

The fashion innovators to know in 2022

French house Hermès turns luxury leftovers into pieces of creative expression, plus the latest in ethical design and the rise of resale.

The federal government funds the repurchase of some units and in theory, industry safeguards mandating maximum carbon emissions per company are meant to drive offset purchases.

But the safeguards set limits which are too high, says Carbon Market Institute chief executive officer, John Connor. Even so, prices have risen as a result of increased demand boosted by fears of more compliance activity. Investor environmental, social and corporate-governance pressure is also forcing more companies to buy offsets, which leads to greater supply for Australia’s premium carbon credits.

Soil carbon is difficult to quantify and check, which is where better technology is helping measurement and processing. This explains the sudden emergence of the so-called method sector, with its focus on soil carbon, carbon capture and storage, biomethane, plantation forestry and blue carbon.

MacLeod notes that at last year’s COP26 UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, nature came to the forefront and “This was evident in deals on rainforests and deforestation and Australia’s lead in carbon farming was clear”.

The big picture statistics are telling: worldwide there are five billion hectares of farm land, which could sequester 80 billion tonnes of carbon a year, the equivalent of 300 giga tonnes of Co2 or six years of global emissions. From a wider perspective it’s all about linking natural capital with farm profitability.

“Australia is a long way ahead of the world on the issue and successive governments need to be applauded,” MacLeod says.

But he notes it is still early in the journey and data needs to be generated. Australia’s clean energy regulations on soil are also onerous and expensive, MacLeod says.

The Macdoch Foundation’s chief executive officer Michelle Gortan told the conference that natural capital in agriculture is more than just soil. “It includes remnant native vegetation, productive pasture-lands and croplands, water resources, agroforestry, environmental plantings and animals, all of which make critical contributions to production, people and the planet,” she said.

See our full list of 100 green power players here

The theory is that increasing a soil’s organic matter content can aid plant growth, increase total carbon content, improve soil’s water-retention capacity and reduce fertiliser use. It’s a field MacLeod has studied extensively and promoted through Macdoch’s Farming for The Future initiative aimed at providing the evidence to support the links between natural capital and farm management.

“There is evidence showing that higher levels of natural capital produce could deliver more benefits for farmers: less variability in production, more drought-resilience, increased profit and greater efficacy,” Gorton further outlined to those in attendance at Glasgow.

“Producers already know that good management of their farm’s natural resources is important to their businesses, but the questions of ‘how much’, ‘how to’, ‘where’, and ‘when’ for them remains largely unknown.”

The Farming for the Future project aims to show “Natural capital becomes a factor of production, like labour or machinery, and is a part of mainstream farm management”.

The ever-modest MacLeod, meanwhile, is quick to push the efforts of others in the field and in his team.

“It’s a bit like being an editor of a newspaper: you don’t have all the answers but you have people who bring their own expertise to create the final product.”

“It’s not my place to tell anyone how to run a farm but I am fascinated by the farming process.”

He cites the work of Ohio State University distinguished professor of soil science, Rattan Lal, who told the Glasgow conference “The health of soil, plants, animals and people is one and indivisible”.

MacLeod says Lal noted a huge increase in chemicals, at an enormous cost to the quality of soils. The use of fossil fuels in industry has destroyed climate, Lal says, while chemicals in combination with farm practice and management have done the same in agriculture.

Glasgow was a return home for MacLeod, who was born in the dairy country south of the Scottish city but never planned a life in the country. This was a byproduct of his return to Australia. “I loved the country life and being in the country,” he says.

MacLeod is married to Rupert Murdoch’s daughter Prue and commutes between their home in the English Cotswolds and the family’s Australian farming interests. He and Prue acquired Wilmot after he left Nationwide News in 2010 and their personal properties include Bloomfield, which is located next to Cavan, near Yass in southern NSW.

MacLeod personally manages the properties but credits people such as Stuart Austin, who answered an advertisement from the Northern Territory to run Wilmot, and Bart Davidson, the Moree-based consultant in product development for Maia Technology.

-

“Bart Davidson was the real genius. Ten years ago he told us that if you want to change the way you farm, you will have to start measuring soil carbon.”

— Alasdair MacLeod

-

At the time Davidson joined the Wilmot team, he was advising cotton farmers in Moree, using Maia’s system-based development to keep a record of the nutrient management plan.

“Stuart and Bart worked closely together, with all the processing handled by Armidale-based Toby Grogan [natural capital manager at Impact Ag],” MacLeod says. “This meant when the Microsoft project was available, we had the measurement processes in hand and at costs a lot lower than the $3 a tonne mandated by the government.”

Grogan describes his work as developing nature-based-solution investments and leading the measurement and monetisation of natural capital.

The actual farm management works on the principles laid down by the likes of ecologist Allan Savory who studied the habits of wildebeest in his native Zimbabwe, where small herds move quickly across different pastures, giving the land time to heal and for ground cover to create soil carbon.

MacLeod said the regeneration project, also known as holistic farming, centres on better cattle management with intensive grazing before allowing the paddock to rest for a long period.

The starting point, back to 2005 and Cavan, was to develop more drought-resistant, profitable farming and the carbon credits are part of what innovative-agricultural adviser Sue Ogilvy calls “the Goldilocks point where you get the right balance between productivity, climate and sustainability”.

See our full list of 100 green power players here

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout