My answer to the first question is “only some parts of News Corp”. And to the second? No one who understood the Coalition’s polling in Queensland thought Turnbull could win a second election. He mishandled the eight-week double-dissolution election campaign in 2016 in which the Coalition lost 14 seats. His chapter on that election is a revelation. More later.

Media and Coalition supporters of the August 2018 challenge by Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton feared a rout in Queensland if Turnbull remained leader. This column at the time argued Dutton, a good minister unfairly maligned by the media left, would have cost the Coalition more seats in southeastern Australia than he could save in Queensland.

The Coalition was lucky events fell the way of incumbent Prime Minister Scott Morrison, whose virtual solo re-election campaign last year was unexpected by most in politics and the media.

What of Turnbull’s assessment that a right-wing political and media cabal has hijacked the party of John Howard and Robert Menzies?

Paul Kelly gave the best answer here last Wednesday: “The trouble with this theory is Scott Morrison’s miracle victory at the election and the pragmatism of Morrison and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg in the (COVID-19) emergency economic measures. No sign of a right-wing cabal in their defining, non-ideological, national interest response.”

ABC 7.30 host Leigh Sales last Monday let Turnbull repeat his assertions about News Corp. Sales works in an environment without diversity of opinion: It may not have occurred to her that inside News Corp different people think differently.

This was obvious to anyone reading the News Corp papers. Different papers and columnists had different views about Turnbull. So when Turnbull’s new book quotes Rupert Murdoch saying “Boris (Paul Whittaker) is the only one” who wanted Turnbull gone, Turnbull is ignoring those within the News stable who made different judgments.

.@TurnbullMalcolm says he sank into a “very, very deep depression†after losing the leadership of the Liberal Party in 2009. #abc730 @leighsales #auspol pic.twitter.com/HSn6mQ2pvV

— abc730 (@abc730) April 21, 2020

One of the company’s most prominent conservative columnists, Miranda Devine, feared the election of a Shorten Labor government should the destabilisation of Turnbull proceed. She was concerned with Labor’s high-taxing agenda and policies that could expand welfare dependency. Devine coined the word Delcons — deluded conservatives — for people who thought a term of Shorten might be a reasonable price to pay to rid the country of Turnbull. This paper’s Janet Albrechtsen took the same view for much of the Turnbull period, but did change her mind after it became clear Turnbull was failing.

Sky News hosts Andrew Bolt and former chief-of-staff to Tony Abbott, Peta Credlin, were tough in their criticisms of Turnbull, especially after the poor 2016 campaign. Paul Kelly, as Turnbull says in his book, was sceptical of the push against the PM. Kelly had seen how damaging the rotating prime ministerial circus had been to the national interest since Julia Gillard’s June 2010 challenge against Kevin Rudd.

Channel 10 political editor Peter van Onselen, a former Sky News host and still a columnist for this paper, wrote often about the high political transaction costs of spills against sitting prime ministers.

This column on December 9, 2018, criticised Turnbull for sniping against the new Morrison government. It argued The Australian had advocated in editorials by current Sky News host Chris Kenny for a better Turnbull government. It said the paper’s Canberra bureau, and especially political editor Dennis Shanahan, had been closer to knowing Dutton’s thinking than other media.

That column concluded: “What to say about Turnbull? He is like his former friend Rudd. Both are extremely wealthy, unable to take criticism and not really from the culture of their parties. The prime ministership was about personal validation rather than the good of the nation. Both had insecure childhoods.” In Turnbull’s favour, he has written only one tome to Rudd’s two that size.

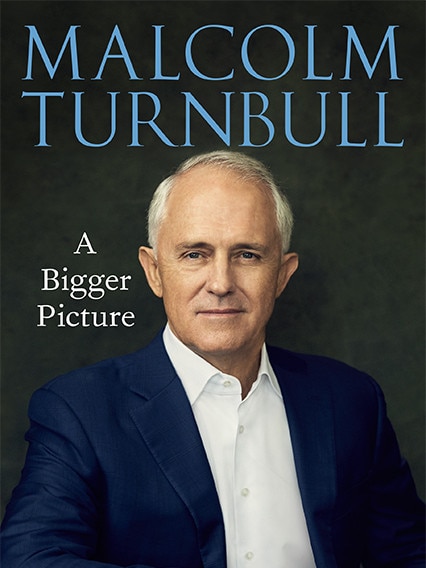

Turnbull’s A Bigger Picture reads like the former prime minister was an observer of his government rather than its leader. Whatever his views of the Murdoch media, there would have been no campaign against him — however Abbott loyalists felt — without his own poor performance in the 2016 election.

In chapter 32 dealing with that poll, he blames man flu, Labor’s dishonest “Mediscare” campaign and the determination of pollster Mark Textor to reject negative campaigning for a result he believes was better than it could have been.

Yet, as leader, it was up to Turnbull to deal with Labor’s scare campaign and the advice of his own paid pollster.

The section of chapter 28 dealing with the new Turnbull cabinet’s inability in late 2015 and early 2016 to prioritise tax reform to grow the economy displays the same attitude.

Turnbull seems to stand apart from discussions about the tax mix before concluding that changes to the GST to lower income tax rates would do little to grow the economy. The road map laid out in 2010 by Ken Henry offered many other reform ideas.

The book’s discussion of the role of then immigration and border protection minister Morrison in destabilising the Abbott government by leaking to The Daily Telegraph similarly undermines the author’s authority. Turnbull, a former journalist, says he understands the media and knew of Morrison’s plans. Yet he seems shocked Morrison leaked to The Daily Telegraph. Yet Canberra has worked that way throughout my 47 years in journalism.

In the interview with Sales, Turnbull referred to media “plutocrats”. It’s the same word he used in 2014 when as communications minister he launched Melbourne property magnate Morry Schwartz’s left-wing vanity publication, The Saturday Paper. He later denied he was referring to Rupert Murdoch in his launch speech when he mentioned “some demented plutocrat” using his papers for political ends.

In my experience good prime ministers can resist demands from media barons, yet this was a less-than-pragmatic way to approach relations with Australia’s largest publisher. Now we find out from his book that two years earlier Turnbull had been intimately involved in the launch of The Guardian Australia, recommending now Guardian editor Lenore Taylor and political editor Katharine Murphy to London-based editor Alan Rusbridger.

Turnbull even says he considered investing $20m of his own money in setting up the Guardian here.

So a former Coalition prime minister was prepared to invest in the most left-wing publication in Australia, not something Howard or Menzies would have considered. This does support criticisms by Bolt and Credlin that Turnbull was leading the wrong party.

Leadership requires a capacity to learn from mistakes. Just as Rudd at 50 treated his cabinet colleagues with the same disdain he had displayed in the early 1990s as head of the office of cabinet for premier Wayne Goss, Turnbull learned nothing from the failure on climate policy that cost him the leadership in 2009. And he learned little from dealing with media billionaires during his time advising Kerry Packer.

Did News Corp campaign for the removal of Malcolm Turnbull as prime minister in 2018? And was that campaign motivated by a fear Turnbull could win the 2019 election?