Turnbull is fixated in his belief a right-wing cabal has corrupted the party of Robert Menzies and John Howard. The trouble with this theory is Scott Morrison’s miracle victory at the election and the pragmatism of Morrison and Josh Frydenberg in the emergency economic measures. No sign of any right-wing cabal in their defining, non-ideological, national interest response.

The book has many contradictions, none more so than Turnbull’s treatment of Morrison — he claims credit for getting Morrison into the job, relentlessly assails his character and reaches the flawed conclusion the Liberal Party “didn’t deserve” to win the election because Turnbull had been dumped. This is a dangerous assertion. How can a former leader be so critical of one of the party’s greatest victories?

The main source for the book is Turnbull’s diary. He says as early as November 2012 Morrison “was sounding me out” about challenging Tony Abbott as opposition leader. In January 2013 he and Morrison kayaked at Port Hacking with Morrison expressing alarm about Peta Credlin and the sort of government Abbott would lead. Turnbull’s assessment of Morrison at this point: it was hard to find an issue on which “he appeared to have a deep or principled conviction”.

Turnbull said he lunched with Morrison at Beppi’s in July 2013 with Morrison saying he expected Kevin Rudd to call the election the next week — he worried “there would be no time to switch to me”. After the Coalition’s victory Turnbull noted: “I am not sure I have the mental toughness of Abbott.”

But on April 5, 2014, Turnbull wrote: “I know I would be a better, more contemporary, more liberal PM than he (Abbott) is.” The same note has Arthur Sinodinos telling him that Credlin “yells at Abbott, treats him with contempt, walks out of meetings and sulks and Abbott has to beg her to return”.

On October 12 with the government in trouble, Turnbull wrote: “Lucy is very, very keen that I retire at the next election and I think I probably should.” On Gough Whitlam’s death he reflected on Gough’s “bigness, generosity and enormous optimism”. He went to Morrison’s electorate on December 10, 2014, with Morrison saying Abbott would have to go “by the middle of 2015 if his performance didn’t improve”. He says Morrison “saw himself as the successor”. At year’s end Turnbull’s diary has Morrison more alarmed. On December 21, Morrison told him: “We will need to remove him (Abbott) before the budget.” His December 30 entry has Morrison saying Abbott and Joe Hockey must do an “amazing turnaround” or “or they will both have to go before the budget”. Julie Bishop joined the Turnbulls at home for New Year’s Eve and was interested in “replacing Joe with me as treasurer”. But when she raised this with Abbott he said it would mean “added leadership stress”.

Turnbull, Morrison and a mutual friend, Scott Briggs, dined at Turnbull’s home on January 19, 2015. He writes: “To my surprise Morrison was advanced in his planning to overthrow Abbott and said the change should happen before the Easter break. He produced a list of names … he believed would vote to roll Abbott. He was concerned about Julie’s ambitions. I tried to assure him she had no interest in playing Lady Macbeth. Morrison said he thought he should succeed Abbott but didn’t want to be seen to challenge him.”

That evening Turnbull told his diary: “We have been very keen not to do anything that could be seen as disloyal to Abbott. Now Morrison has decided he wants to push him over and I am uncomfortable about that. Plan for the contingency yes, but do not have a hand in bringing it about.”

Turnbull correctly saw the Prince Philip knighthood as a tipping point. The tide was turning against Abbott. Turnbull had extensive talks at the end of January, the weekend the LNP government fell in Queensland. He told his diary: “Julie Bishop — spoke to her at length. She is of a mind to be the leader but only on the basis that I would do Treasury … I just am not sure it would work … We discussed it at great length.”

He wrote: “Morrison: had several discussions with him. He is a little all over the shop and talks about being PM himself but seems to recognise it’s too soon for him. Christopher (Pyne) who had told me he thinks Abbott is completely terminal has, according to Morrison, floated a Morrison/Pyne ticket! Ye gods, that would really work.

“The problem with Morrison it seems to me is that he wants to marginalise Julie. Now, I agree she is a risk as PM, but it is absurd as I point out to him to take her deputy role … the optics of doing Julie over are horrific and if he is Treasurer he is effectively the No 2 anyway.”

On February 2, 2015, Turnbull summarised his thinking: “Abbott’s position is untenable. He is so loathed in the community, his judgment is flawed and frankly crazy, he has to go. The new leadership team it is generally accepted is me, Julie and Scott. The real issue is who is PM between me and Jules.” Meanwhile, a group of West Australian MPs led by Luke Simpkins pressed the button on a spill motion, with Turnbull noting they “were all right-wingers, no fans of mine”. He branded some of them “climate change deniers”, his worst insult.

On February 8, Turnbull and Bishop met at a fundraiser for the Bellevue Hill branch and, finding a private room, rang Morrison; agreement was reached on what they would do if the spill motion were carried: the new team would be Turnbull, Bishop, Morrison, the latter as treasurer. The spill was lost 61-39 but perfect for Turnbull. He had no blood on his hands. Abbott was fatally weakened. The alternative leadership team was now sorted by the Big Three.

At the cabinet meeting the evening of the spill Turnbull got assertive. He insisted on a political discussion. Advisers left the room. Turnbull writes that Abbott pleaded: “I just need time to prove that I can recover.” He said the mood was “as bleak as it could be”. He reveals Peter Dutton being blunt in the cabinet room: “Tony, you can’t expect us to go over the cliff with you. Malcolm is the only alternative and if you can’t improve, then we expect you to make an orderly transition.” Turnbull said: “You could have heard a pin drop.”

The next month, March, Turnbull checked with the two emerging figures on the right, Dutton and Mathias Cormann. He summarises his diary entry: “He (Dutton) completely dismissed Julie (they loathed each other) and told me that both Abbott and Hockey should go — Hockey to be replaced by Morrison. Dutton said I needed to work to win over more of his colleagues in the hard right. On timing, he said they would need to suffer more from Abbott’s ineptitude. Cormann, on the other hand, while of the same opinion on leadership, was more open to a pre-budget challenge.”

But Turnbull fell out badly with Dutton in June over his plans to strip citizenship from suspected terrorists. This issue split cabinet, with Turnbull challenging the Abbott-Dutton position as unconstitutional. He said Dutton was dripping with contempt, “almost sneering at me”. On June 21, after Turnbull talked with Sinodinos, his diary read: “Arthur, like me, believes Abbott is a dangerous prime minister, a threat to the nation and its security. The question is how and when we can move on him.”

Turnbull believed Abbott “at every turn” exploited the terrorist threat to “heighten fear and anxiety” to save his job. There is no way Abbott will not respond to such accusations. The only conclusion from this book is that Abbott was doomed long before the failed February 2015 spill motion. As for Morrison, he has a crisis to manage, but at some time he will reply to the litany of claims about him, far exceeding just one column.

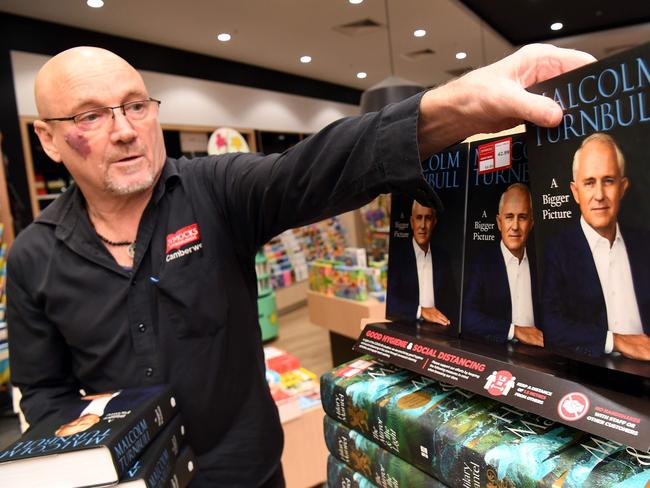

Malcolm Turnbull has delivered his view of history — revealing, engrossing, explosive, self-serving, disloyal and contested — but don’t believe it will be forgotten in the dustbin. No former prime minister has written such a memoir and the Liberal Party must live with its consequences.