What Malcolm Turnbull failed to mention in memoir

The moment Malcolm Turnbull destroyed his Liberal Party leadership is not in his book.

It was one of the most telling moments in recent political history because it was pivotal in exacerbating more than a decade of climate and energy wars in federal parliament and the Coalition parties. It has long confounded me how this tipping point was missed, overlooked or forgotten.

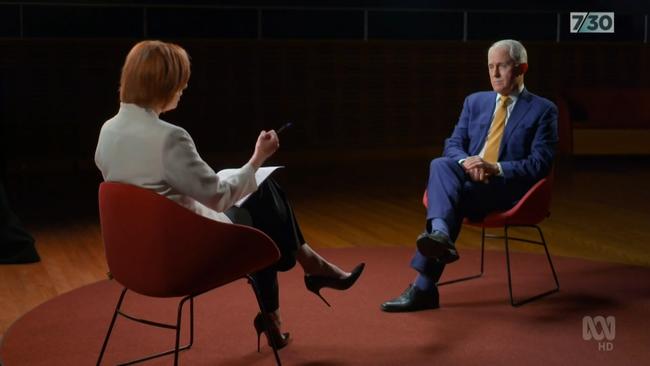

As Turnbull’s chief-of-staff at the time I have kept professional and personal confidences and not written about it in detail. But Turnbull told my colleague and former Labor staff member Troy Bramston this week: “There is not much point in writing a memoir if you cannot write it truthfully … it’s important that people know what happened.” Therefore it is time to recount this episode that explains much, not only about 2009 but 2018 too.

Leadership changes are organic, they have a life of their own. Much like a pandemic, myriad factors can inflame them; they can be suppressed, then suddenly run riot; and at their heart is a contagion. For Turnbull, both times, the catalyst was climate policy; specifically, his determination to be progressive on climate action by dealing with Labor. Tellingly, in A Bigger Picture, he wonders which Liberal leader, other than he, could “take climate change seriously and be a sincerely constructive partner with Labor?”.

This Liberal leader repeated the same fatal mistake nine years apart. Both times there were cross-currents to navigate: conservative MPs who could never abide Turnbull as leader, personal enmities and ambitions at play, along with media games.

In 2009, Turnbull’s Godwin Grech folly had exploded in his face and undercut public trust and internal confidence. Rudd was trying to deliver his emissions trading scheme promise, an election commitment on the “greatest moral challenge” of our time, and Turnbull wanted to help him.

Whatever you thought of the policy detail, it was a defendable strategy to neutralise a contentious policy debate and shift to other issues such as economic management and border protection. But Turnbull faced growing resistance within the Coalition from those who worried about the economic impact, didn’t like aspects of Labor’s design or were sceptical about climate change.

To deliver for Rudd, Turnbull had to corral his own party, which was like herding cats. Instead of making it easy for him, the Labor prime minister foolishly revelled in his rival’s pain (the karma bus would hit him later).

Still, as parliament went into recess at the end of June, the Coalition partyroom settled on a rational compromise: it would refuse to pass Rudd’s carbon pollution reduction scheme until after the Copenhagen Climate Summit, due in December. This made sense because it would be foolish to commit to a scheme before knowing what the rest of the world was doing, and it was self-evidently logical in a way the public and all elements of the party could embrace.

With this position, conservative MPs had gone as far as they could for Turnbull. But he hated it.

We discussed his reasons as we drove back to Sydney from Canberra. Turnbull worried critics would attack him daily as a climate denier while the process played out. This concern showed the political weakness prevalent in the moderate wing of the Liberal Party, where they often worry too much about arguments marshalled against them rather than ensuring their case is superior.

Turnbull’s other reason was a dilemma for the Coalition. If Rudd pushed the parliamentary schedule and the Coalition stuck to its guns, Labor could force a climate change double dissolution before the end of the year, even before Copenhagen, which could be disastrous for the Coalition and its leader. I recall Senate leader, climate sceptic and Turnbull malcontent Nick Minchin, around this time predicting Copenhagen would end in tears. But the accepted wisdom was that a deal, some form of global consensus, was a foregone conclusion.

My rather lame but practical advice to Turnbull was that denying Rudd his CPRS until after Copenhagen was a head-nodder that would give him a strong case to run for months before considering the next play. Sometimes politics needs to be like that: stick to your fundamental principles and see where it takes you. Turnbull was never convinced, essentially because he wanted an ETS but also because he couldn’t see where the argument would lead him. He felt his party had lumbered him with a position that was neither fish nor fowl.

On the morning of July 20, I was flying to Queensland for a few days off and was nervous about Turnbull’s scheduled interview with Fran Kelly on Radio National Breakfast. By the time I landed, the interview was done, my phone was alive with text messages from Liberal MPs and I’d been sent a transcript that explained why.

Late in the interview Kelly gently pushed Turnbull on whether the Coalition might pass Rudd’s CPRS if it were amended to its satisfaction. “So, it sounds like you’re considering voting for this bill some time either August or November if you can get some changes through?” she asked.

Turnbull’s answer was incendiary to his own party. “Well, Fran, it depends on what the changes are,” he said, “but there is an overwhelming consensus in the business community — and, of course, these are the people whose businesses have the thousands of employees’ jobs which are at stake — there’s an overwhelming consensus that the law should be changed and we should seek to advance and promote those changes.”

In an instant, the Copenhagen ultimatum was gone, the Liberal leader had unilaterally changed the Coalition’s position. This is how political parties fracture — MPs give their leaders some latitude but don’t like being taken for granted.

With fellow staff member Peta Credlin, we quickly organised a shambolic phone hook-up of shadow cabinet. Turnbull was on his mobile, boarding a plane, and in a messy and frantic conference call the shadow cabinet agreed to change the Coalition’s climate policy retrospectively to match the leader’s interview.

Imagine what that did to the forbearance of Liberal backbenchers. Their hard-won position had been junked; Turnbull was more inclined to meet Labor’s demand than theirs. Little of this was reported at the time; I think this newspaper’s political editor, Dennis Shanahan, was one of the few to recognise the significance.

For Liberal MPs who heard about the interview, shadow cabinet members on that crazy call, and to me, it stands out as the moment Turnbull crossed the Rubicon. It locked him into a period of trying to negotiate a deal with Labor while keeping his partyroom at bay, and on the eve of Copenhagen Abbott took the leadership and opposed the CPRS.

When he tore down Abbott as prime minister six years later, Turnbull couldn’t leave climate and energy alone. In 2016 a senior cabinet minister spoke enthusiastically about Josh Frydenberg’s promotion to the role of environment and energy and I begged to differ, seeing it as an impossible task. In my view Frydenberg could deliver a policy to satisfy his prime minister and destroy the government; or provide a policy the government needed and destroy his career. Turnbull, with Frydenberg by his side, announced the ratification of the Paris Agreement, without partyroom or parliamentary debate, the day after Donald Trump won the US election partly on a promise to leave Paris.

Frydenberg deftly tried to pick the middle ground but in the end satisfied Turnbull’s climate demands. It didn’t quite destroy the government, just the prime minister. The irritant that saw Turnbull torn down was the National Energy Guarantee that would write the Paris targets into Australian law; a climate and energy policy the Labor Party would support.

Twice, nine years apart, Turnbull came up with climate positions that mollified Labor but alienated his own partyroom.

There is a telling postscript to all this buried back in the controversies of 2009. It happened just a week after Turnbull unilaterally abandoned the Copenhagen holdout and agreed to negotiate amendments with Labor.

The Australian published a Newspoll on emissions policy options. It showed, even then, without anyone advocating the case, 45 per cent of voters favoured waiting until after Copenhagen before finalising an emissions trading scheme, versus 41 per cent who favoured immediacy. If Turnbull had held the line on the CPRS for one more week, he would have seen that evidence of public support for a position he had junked in a radio interview.

We now know Copenhagen did collapse — Rudd claimed he was ratf..ked by the Chinese, and when he was eventually given his climate double-dissolution trigger, he squibbed it and the public instantly lost faith in him.

Politics is never easy, much less climate and energy policy.

But for all the talk of media conspiracies, personal revenge, disloyalty and incompetence, this was the reality of how Turnbull twice skewered himself on the same policy fault line.

The moment Malcolm Turnbull destroyed his Liberal Party leadership — the first time, in 2009 — is not in his book. It is a serious omission because not only did it precipitate his demise, the rise of Tony Abbott, a Coalition reversal on climate policy and the destruction of Kevin Rudd, it also prefigured his downfall as prime minister nine years later.