Three decades before the Albanese government’s plan for an Indigenous voice to parliament, the key question at this newspaper was how to protect Aboriginal women and children in remote communities.

While powerful black men battled for control of $1.1bn a year of funding through the old ATSIC (the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission) and Indigenous academics campaigned for land rights, a new brand of reformers began talking about the wellbeing of Aboriginal families.

The late Galarrwuy Yunupingu and Noel Pearson, in the early 1990s, started discussing the effects of sit-down money on remote Aboriginal life. In most of the media, such talk was treated with suspicion.

Journalist Rosemary Neil and this columnist, then editor of The Australian under then editor-in-chief Paul Kelly, were criticised by ABC and Fairfax editors at the 1994 Walkley Awards presentation in Melbourne, after Rosemary’s piece – about the true extent of the violence by Aboriginal men against women and children in outback communities – won a gong for best feature writing.

Our critics that night thought the piece was racist. The media collective was much keener on the thoughts of metropolitan Aboriginal rights campaigners than on reporting what was actually happening in remote communities.

ATSIC was eventually scrapped after scandals involving its chair, Geoff Clark, and deputy chair, Sugar Ray Robinson.

The land rights fight was won with Mabo in 1992 and Wik in 1996. Despite vast areas of the country now under Native Title and billions of dollars of royalties being paid by mining companies to traditional owners, there has not been much improvement in rates of violence and substance abuse in remote Aboriginal Australia.

Two generations of Aboriginal academics have gone on to graduate from universities. But kids and their mums in remote Australia have little hope of emulating improvements in the lives of their city cousins.

Last week Northern Territory police introduced a 72-hour curfew in Alice Springs after four off-duty police, three of whom were female, were assaulted by 20 Aboriginal children at 2.15am on July 7 on a walkway across the Todd River.

Too few reporters asked the right questions: where were the children’s parents and how are these kids going to cope when they have their own families? At the ABC it was all about spending more money as part of a federal package of $250m for disadvantage and youth crime promised by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese when he went to Alice last year.

History should tell journalists that no amount of spending, no action by government-appointed bureaucrats and no rights campaign will fix such issues. Aboriginal leaders need to be empowered to help their people engage in meaningful work and responsible parenting.

Pearson has been saying exactly this since the mid-1990s. In a 1999 speech to the Brisbane Institute, he laid out his thoughts for family reform and the need for Aboriginal parents to work and take responsibility for their own lives.

Pearson said: “The provision, without reciprocity, of income support to able-bodied people of working age can be seen as negative welfare, inducing passivity and dependence. Community leaders must develop a conscious long-term strategy for their home regions, and work with the state in reforming welfare resources. They must understand the central importance of education and the encouragement of enterprise, achievement and success among their people.”

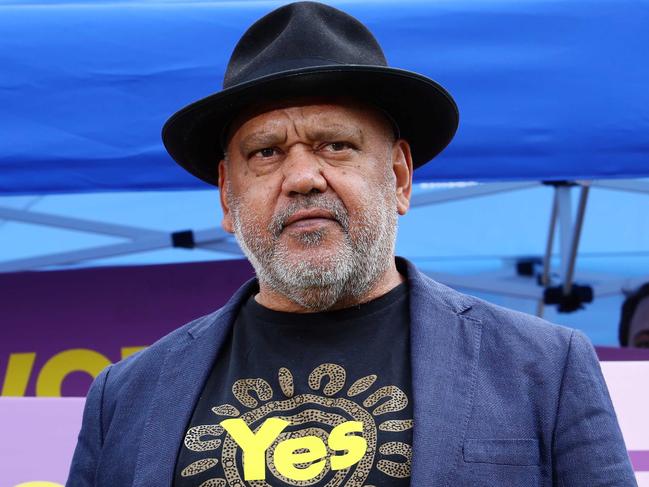

The Courier-Mail in Brisbane campaigned with John Howard’s federal Coalition government and Peter Beattie’s state Labor government to support Pearson’s eventual introduction of the nation’s first income management scheme that still exists on Cape York today. Yet in the 25 years since then, remote Aboriginal life has not improved. Warren Mundine, who was a “no” campaigner, last Thursday told The Daily Telegraph that locking up kids such as those in Alice Springs would only create people who spend a lifetime in the criminal justice system. Work and education were the key.

The previous day this newspaper – across the top of page one – quoted Coalition Aboriginal Affairs spokeswoman Jacinta Nampijinpa Price. Her plan for Aboriginal advancement would involve “welfare-dependent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’’ doing the jobs in their communities now done by fly-in fly-out workers, so they could “meet the standards other Australians expect to meet”.

It is against this background that a story by the Herald-Sun’s James Campbell, a short piece in the Guardian and another from ABC online appeared in the past week. They concerned an Adelaide University study into the effects of the abolition of the cashless debit card – one of the Albanese government’s first acts in power.

The card was introduced in trials in 2016 after various reviews of an original proposal by miner Andrew Forrest. While there was legitimate debate about the punitive impact of the card, its axing effectively privileges the views of left-wing rights campaigners who saw it as discriminatory.

The 165-page study – Review of the Impact of Cessation of the Cashless Debit Card: Final Report – looked at four communities that first trialled the card: Ceduna, East Kimberley, WA Goldfields and Bundaberg-Hervey Bay. It concludes exactly what people who understand the history of the issue would have expected.

Some people who did not really need income management felt a stigma had been lifted from them. Others, especially mothers, felt the loss of the card keenly as the man of the house took cash associated with welfare payments to the pub, the TAB or the local drug dealer. The card had quarantined 80 per cent of payments for tap transactions for food and necessities.

Back in the 1990s, Pearson had argued with Howard’s minister for Aboriginal affairs, the late senator John Herron, that welfare linked to the number of children in a family needed to be controlled so children on Cape York could receive fresh food, milk and clothes to attend school.

As the Herald Sun’s report of the Adelaide study – released at 10pm on Friday, July 5, under an Opposition freedom of information request – says, the card’s axing triggered “a surge in gambling, public drunkenness and alcohol-related violence, with more children going hungry, missing school and wandering the streets at night”.

In all areas where the card had been abolished there had been “a large increase in the numbers of people seeking emergency relief services” including “access to food vouchers and boxes, clothes and the payment of items such as school fees, fuel and car registration”.

One Ceduna woman quoted on page 37 of the report discusses a friend who has signed up for new voluntary income management: “She loves it because, I’ll be honest with you, her partner, he does heavy drugs … so she needs to stay on it because she needs to make sure that her children have got food.”

Another Ceduna resident said of the old card: “People were still drinking, yes. But when we had the card they were drinking 20 per cent of their income versus 100 per cent of their income.”

Others from various trial areas noted an increase in spending on illegal drugs, particularly meth, since the card’s abolition.

Yet in much of the media, income management has been reported as racist government paternalism.