Social media certainly gives the ill-informed the ability to trumpet opinions more widely than in earlier eras, but much of the wider triumph of opinion is down to cheap clicks to online media businesses and shouty content in traditional media that consumers can agree with. Reporters have a duty to swim against this tide.

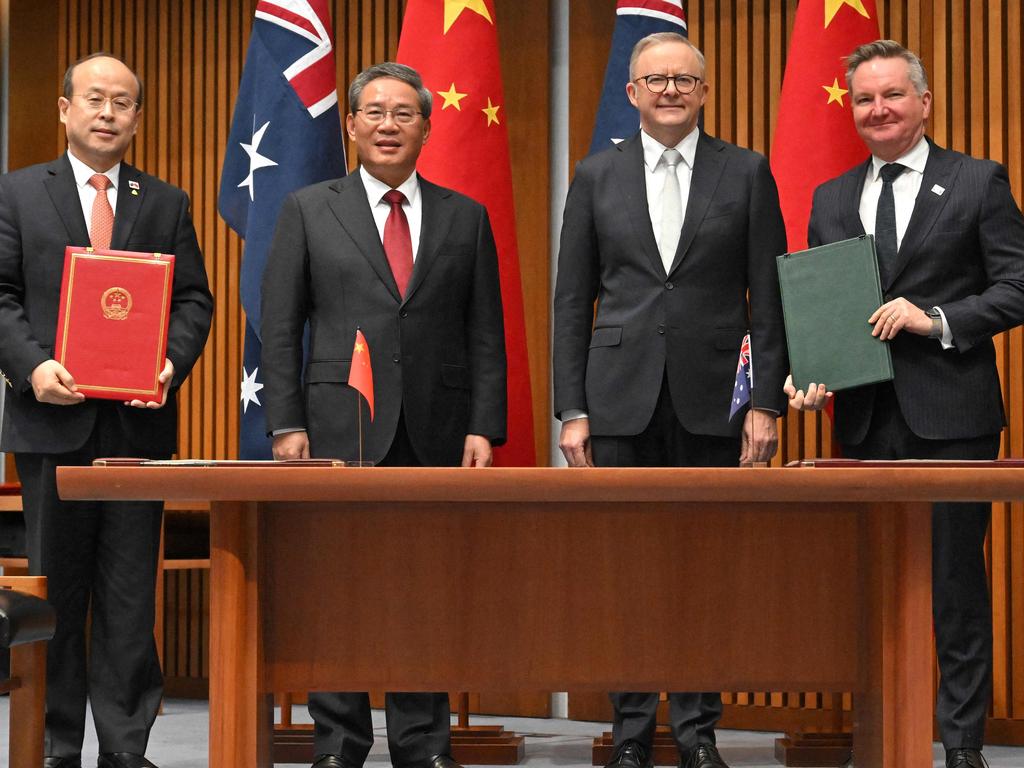

News coverage of last week’s visit by Chinese Premier Li Qiang is illustrative.

Had China’s diplomats not tried to shut out Sky News Australia reporter Cheng Lei from two Canberra events, our media would have let Prime Minister Anthony Albanese get away with a largely false narrative: he and Foreign Minister Penny Wong are repairing the China relationship broken by Albanese’s predecessor, Scott Morrison.

Patricia Karvelas said as much on Friday when she introduced Defence Minister Richard Marles on ABC Radio National.

Australia, Karvelas said, had made progress in re-setting its “once shattered” relationship with China.

Yet public outrage at China’s bullying of Cheng Lei, an Australian wrongly jailed for three years by Beijing, effectively undermined that Labor narrative. If ever Australians could see the ugly face of China’s bullying, watching Chinese officials inside Australia’s parliament trying to stop cameras filming an Australian journalist left no doubt China disrespects Australia.

Political journalists who have played along with the myth of the Coalition destroying Australia’s China relationship should hang their heads in shame.

The rift started during Malcolm Turnbull’s prime ministership when, in August 2018, Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei was banned from the 5G telecommunications rollout on security advice.

Other countries followed soon after, including the US, Japan, India, New Zealand, Singapore, Norway and Denmark. In April 2019, Labor ruled out reversing the Huawei ban if it was to win that year’s election.

The Huawei ban here came only months after Turnbull first flagged new foreign interference legislation in June 2018. Turnbull was right on both counts.

The Australia-China relationship really hit the rocks at the end of January 2020, when prime minister Morrison banned flights from China in the early stages of the spread of Covid-19, and then called for an international investigation into the emergence of the pandemic in the city of Wuhan. Morrison was right on both counts.

China responded with a series of bans and restrictions on Australian exports. Barley, wine, lobsters and beef from some abattoirs was banned. Some local restrictions were applied on shipments of Australian coal. This all came despite the China-Australia free trade agreement signed in 2015 by Tony Abbott’s Coalition government.

Last week on Sky News’ Sunday Agenda and on ABC’s 7.30 on Tuesday, Trade Minister Don Farrell was given soft treatment to claim the Labor government’s diplomatic efforts were succeeding in having those bans reversed.

The truth is that just as China’s bullying of Cheng Lei backfired, its strategy of using trade to punish Australia for speaking up on Covid was a spectacular own goal. Some of the world’s leading economics and foreign policy journals, including The Economist, The Atlantic and Foreign Policy, have not only called out the failure of China’s bullying but praised Australia for resisting pressure from the world’s number two economy.

In November 2021, Foreign Policy wrote: “But if Beijing hoped to punish Canberra for its defiance with economic pain – and send a warning to other countries not to oppose China – it has failed on both counts. The impacts on Australia have so far been surprisingly minimal. That fact will not be lost on other countries that have differences with China.”

Many Australian journalists during the China freeze seemed unaware of the reality of our economic position. Partly because of rising coal and iron ore prices – and partly because our most affected exporters found alternative markets – China’s bans were estimated by a Productivity Commission report to have cost us nine one-thousandths of a percentage point of GDP, or less than $225m.

As The Australian’s Tom Dusevic reported on July 24 last year, if anything, the bans “have been an inglorious own goal for our largest trading partner”.

While that sum would have been tough for some producers, many journalists reacted as if Australia was on its knees. And while it’s better in diplomacy to shout as little as possible and have disagreements behind closed doors, the evidence is China was determined to subjugate Australia, at least economically, and had been doing so for decades before the export bans.

A report by Peter Hartcher in The Sydney Morning Herald on November 7 last year argued “we received public notice of Beijing’s intentions to dominate Australia in a revelation in 2005”.

A Chinese diplomat working at the Sydney consulate defected. The diplomat, Chen Yonglin, said the Communist Party of China “had begun a structured effort to infiltrate Australia’’ because it saw us as a “weak link in the Western camp”. This was much more than just spying.

“The party ran an influence campaign, partly through its United Front organisations operating in Australia. Rich business people were dispatched to live in Australia to set up empires of influence. Their methods included political donations, sponsored trips to China, major investments and board appointments,” Hartcher wrote.

Between 2005 and the start of the pandemic, China’s share of our exports rose from 12 per cent to 38 per cent.

Even the US thought Australia could flip. Hartcher quotes White House Indo-Pacific co-ordinator Kurt Campbell confirming that Washington thought this possible.

But by early 2022, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken told the SMH: “I think China has lost more than Australia has in its efforts to squeeze Australia economically.”

This newspaper’s foreign editor, Greg Sheridan, last Tuesday nailed the real import of the Cheng Lei incident: it revealed Albanese’s weakness. The PM had already appeared weak when he seemed not to have raised with China’s President, Xi Jinping, at an APEC meeting in San Francisco last November the Chinese navy’s firing of sonar at Australian naval divers only days before.

While many journalists tiptoe around such issues, the public pounced last week. Why was an Australian journalist being bullied by Chinese officials inside Australia’s parliament?

Discussing our China trade relationship, reporters should have been led by the facts rather than by Labor’s spin. The Coalition did a lot wrong during the Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison years, but it mostly got China right and it certainly got the AUKUS submarine partnership with the US and UK right.

Journalists need to take care not to appear to be pushing the false narratives of their preferred side of politics.

ABC 7.30 host Sarah Ferguson on Wednesday interviewed Liberal energy spokesman Ted O’Brien about the Coalition’s new nuclear power policy. Why could Ferguson not concede O’Brien’s point about the many unknown costs in Labor’s renewables rollout across large tracts of the continent?

She sounded like an ALP staffer. Many countries rely on nuclear power but none rely exclusively on wind and solar. Countries relying on renewables largely tap hydro-electric power.

If facts can no longer be accepted by the community, let alone by reporters, then journalism is being destroyed by opinion.