If anything, it’s been an inglorious own goal for our largest trading partner – denying Chinese consumers our wine, lobsters and beef, and factories raw materials, while galvanising Australia and other free nations not to be intimidated by Sino trade aggression.

Coercive actions impose a cost, one some nations are prepared to bear if they get tangible benefits. We’re still standing and have cracked new export markets, while China has lost incalculable global prestige for this and other clumsy moves in the “wolf warrior” era.

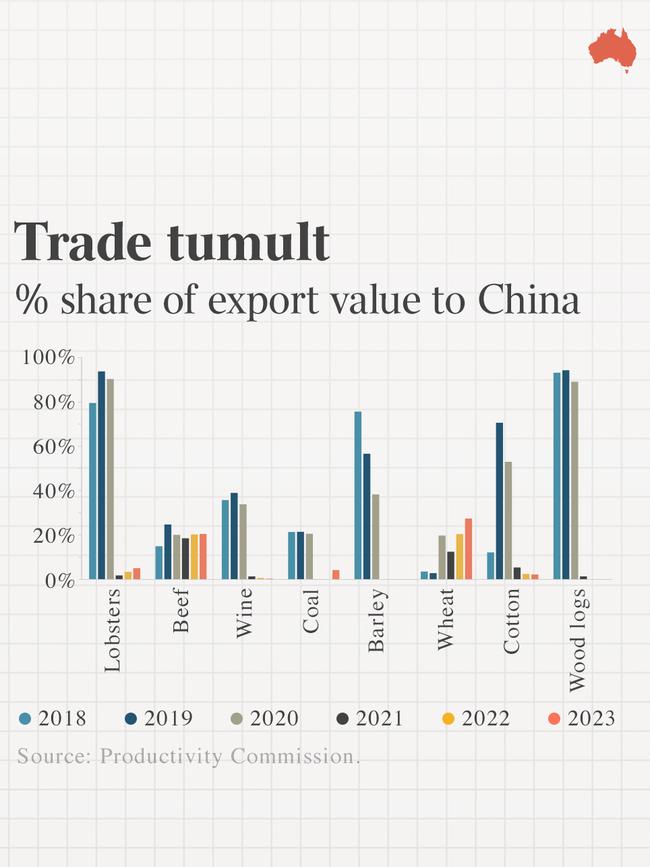

In the first year of the pandemic, Beijing slapped punitive tariffs on Australian barley and wine; banned beef from some local abattoirs; put wheat and lobsters through more inspection hoops; ordered mills to stop buying our cotton; banned timber from certain regions; and banned some coal imports on environmental grounds.

Now in an economy-wide simulation, the Productivity Commission estimates China’s punitive actions reduced our gross domestic product by 0.009 per cent, less than one-hundredth of 1 per cent or about $225m in today’s dollars.

Sounds hefty, but Australia’s GDP is about $2.5 trillion. So the loss of output from China’s trade assault was like shutting down our economy for 48 minutes, or one-half of a Matildas’ game (with injury time).

There’s a 0.4 per cent loss in national purchasing power – known as “terms of trade” – but since early 2020 the world has given us a 25 per cent pay rise on this score.

In global trade, when a shock occurs and one door closes, others open, relative prices change, and consumers, government and the owners of capital adjust to the brave new world.

In its model, the commission explains in its recently released Trade and Assistance Review, China’s prohibitive tariffs reduce the prices Australian producers receive and leads Australian exporters to reallocate production to domestic and foreign markets.

Of course, the value of Australian exports of the five affected goods modelled – cotton, seafood, coal, wine and wood – declines.

This leads to a reduction in outputs and a reallocation of resources away from the production of these goods.

In the simulation, the prohibitive tariff reduces the value of Australia’s total exports to China by 6.7 per cent.

As China’s demand for Australian exports declines, prices decline. This makes the targeted exports more attractive to other trading partners, who increase demand for Australian exports by 2.2 per cent.

This trade diversion results in a tiny decline in the value of Australia’s total exports. Globally, there is no appreciable net effect on trade, but China’s imports from other sources increases.

The reduction of China’s demand for the affected Australian products reduces the demand for inputs to these products, which in turn reduces their price, and therefore the cost of production in Australia.

“This makes Australian products cheaper in world markets: lower production of exports to China is offset by higher production of exports to other destinations,” the review said.

“Increased production attracts foreign capital. The inflow of foreign capital offsets the decline in GDP that would have occurred, had there been no reallocation to other destinations.”

This small inflow of foreign capital means Australia’s real GDP remains stable although some of that income goes to foreigners, so our gross national product falls by one-hundredth of 1 per cent.

The commission’s review found Australian exports proved to be mostly resilient against China’s onslaught: barley and coal exporters were successful in finding other markets, for example. The value of beef and wheat exports to China did not see significant falls – likely due to the partial nature of the measures.

Some businesses paid a heavy price. There were big falls for lobsters and wine for Australian producers whose exports were centred on the Chinese market.

“That said, after initially increasing exports to their original markets, wine exporters developed new markets,” the review said. “In the case of products with limited perishability, like wine, the costs to exporters might be from deferred sales rather than not being able to sell the good at all. And some exporters may have even enjoyed an increase in the value of stock that ages well.”

Now you can take issue with the free-trade boosterism of the commission’s approach but it accords with developments in the real world.

The pain is concentrated in the targeted sectors. An important caveat is the analysis “does not take into account the costs to those directly targeted businesses of seeking new markets”.

Within Australia, the most noticeable effects are that resources are reallocated from affected producers in the primary sector to the rest of the economy. In the model, manufacturing is a beneficiary, with increased output.

That said, the simulation shows (surprise, surprise) a flexible international trading system is important in facilitating adjustments needed to minimise the effects of the trade sanctions.

“Despite short-term costs, there are often long-term gains from diversification, which supports supply chain resilience and risk management,” the commission said. “Overall, reducing Australia’s exports of the affected products results in a reorganisation of economic activity globally and within Australia.

“Although there are some costs, they’re relatively small once all economies have adjusted.”

As they say in diplomacy, looks like China may have to use honey rather than vinegar to get a win.

Beijing’s brutish lunge at economic coercion may have crippled some of our primary producers, but it had an infinitesimal impact on exports and the broader economy.