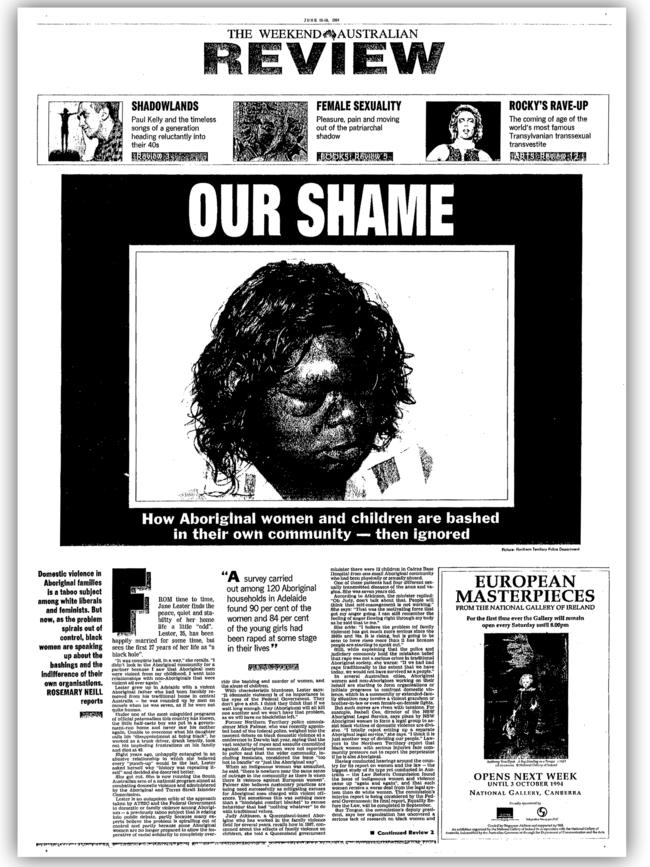

How Aboriginal women and kids are bashed – then ignored

First published by The Australian in 1994, this story changed the course of debate about violence in remote Indigenous communities. As the masthead turns 60, we are republishing this groundbreaking piece of journalism.

- First published June 18, 1994

From time to time, Jane Lester finds the peace, quiet and stability of her home life a little “odd”. Lester, 35, has been happily married for some time, but sees the first 27 years of her life as “a black hole”.

“It was complete hell in a way,” she recalls. “I didn’t look in the Aboriginal community for a partner because I saw that Aboriginal men were violent from my childhood. I went into relationships with non-Aboriginals that were violent all over again.”

Lester grew up in Adelaide with a violent Aboriginal father who had been forcibly removed from his traditional home in Central Australia – he was rounded up by men on camels when he was seven, as if he were not quite human.

Under one of the most misguided programs of official paternalism this country has known, the little half-caste boy was put in a government-run home and never saw his mother again. Unable to overcome what his daughter calls “his disappointment at being black”, he worked as a truck driver, drank heavily, took out his imploding frustrations on his family and died at 42.

Eight years ago, unhappily entangled in an abusive relationship in which she believed every “punch-up” would be the last, Lester asked herself why “history was repeating itself” and decided she deserved better.

She got out. She is now running the South Australian arm of a national program aimed at combatting domestic violence and administered by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission.

Lester is an outspoken critic of the approach taken by ATSIC and the federal government to domestic violence among Aborigines – a previously taboo subject that is edging into public debate, partly because many experts believe the problem is spiralling out of control and partly because some Aboriginal women are no longer prepared to allow the imperative of racial solidarity to completely override the bashing and murder of women, and the abuse of children.

With characteristic bluntness, Lester says: “it (domestic violence) is of no importance to the eyes of the federal government. They don’t give a shit. I think they think that if we wait long enough, they (Aborigines) will all kill one another and we won’t have that problem, as we will have no blackfellas left.”

Former Northern Territory police commander Mick Palmer, who was recently appointed head of the Federal Police, weighed into the nascent debate on black domestic violence at a conference in Darwin last year, saying that the vast majority of rapes and assaults committed against Aboriginal women were not reported to police and that the wider community, including feminists, considered the issue “too hot to handle” or “just the Aboriginal way”.

When an Indigenous woman was assaulted, he said, “there is nowhere near the same sense of outrage in the community as there is when there is violence against European women”. Palmer also believes customary practices are being used successfully as mitigating excuses for Aboriginal men charged with violent offences. Yet sometimes this was nothing more than a “hindsight comfort blanket” to excuse behaviour that had “nothing whatever” to do with traditional values.

Judy Atkinson, a Queensland-based Aborigine who has worked in the family violence field for several years, recalls how in 1987, concerned about the effects of family violence on children, she told a Queensland government minster there were 12 children form one small Aboriginal community who had been physically or sexually abused.

One of these patients had four different sexually transmitted diseases of the anus and vagina. She was seven years old.

According to Atkinson, the minister replied: “Oh Judy, don’t talk about that. People will think that self-management is not working.” She says: “That was the motivating force that got my anger going. I can still remember the feeling of anger flowing right through my body as he said that to me.”

She adds: “I believe the problem (of family violence) has got much more serious since the 60s and 70s. It is rising, but is going to be seen to have risen much more than it has because people are starting to speak out.”

Still, while explaining that the police and judiciary commonly hold the mistaken belief that rape was not a serious crime in traditional Aboriginal society, she warns: “If we had had rape traditionally to the extent that we have today, we would not have survived as a people.”

In several Australian cities, Aboriginal women and non-Aborigines working on their behalf are starting to form organisations or initiate programs to confront domestic violence, which in a community or extended-family situation may involve a violent grandson or brother-in-law or even female-on-female fights.

But such moves are riven with tensions. For example, Isabell Coe, director of the NSW Aboriginal Legal Service, says plans by NSW Aboriginal women to form a legal group to assist black victims of domestic violence are divisive. “I totally reject setting up a separate Aboriginal legal service,” she says. “I think it is just another way of dividing our people.” Lawyers in the NT report that black women with serious injuries face community pressure not to report the perpetrator if he also Aboriginal.

Having conducted hearings around the country for its report on women and the law – the biggest study of its type yet conducted in Australia – the Law Reform Commission found the issue of Indigenous women and violence came up “again and again”, and that such women receive a worse deal from the legal system than do white women. The commission’s interim report is being considered by the federal government; its final report, Equality Before the Law, will be completed in September.

Sue Tongue, the commission’s deputy president, says her organisation has uncovered a serious lack of research on black women and violence and a “critical” need for legal services specifically designed for them. Aboriginal legal aid services will not handle black-on-black disputes and are defendant-oriented and, as such, will not represent a battered Aboriginal woman if it means prosecuting an Aboriginal man.

A survivor of domestic violence, Coe denies this policy leaves battered black women – who are usually the victims rather than the perpetrators of family violence – at a disadvantage. “The thing is, Aboriginal men are victims too,” she says.

Yet the latest edition of a family violence handbook, Through Black Eyes, which is funded by ATSIC, underscores the gravity, complexity and disturbing frequency of violence among the Indigenous population. The book, published by the Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care, states that:

*Up to and over 50 per cent of Aboriginal children are victims of family violence and child abuse.

*In the early 1990s, a survey carried out among 120 Aboriginal households in Adelaide found 90 per cent of the women and 84 per cent of the young girls had been raped at some stage in their lives.

*A related statistic says that, in most states, more than 70 per cent of assaults on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are carried out by their boyfriends or husbands. Therefore one can only assume that many of the above-mentioned rapes are carried out by black men. (The handbook says rape is not talked about in Aboriginal communities and that rape victims are rarely adequately supported.)

An ATSIC video on domestic violence, Beyond Violence, Finding the Dream, says in one unnamed Australian city one in three Aboriginal women have had suicidal thoughts and one in five have attempted suicide.

Lester and other Aboriginal women say it doesn’t “add up” that ATSIC is spending so little addressing the problems graphically outlined in the book and video. The 3½-year program on which Lester works is national and costs $1.3m a year. It is the only program ATSIC runs that specifically addresses family and domestic violence, even though the administrative body receives annual funding of close to $1bn.

Though Leicester is pleased with the way her program is progressing, she says the manner in which ATSIC and some Aboriginal host organisations set up the Family Violence Intervention program was far from satisfactory. She claims the scheme was devised in two days, and that she moved to Port Augusta from Adelaide, to find she had no office or phone and a management committee “who weren’t actually meeting”. As such, she says her service “started in my rust-bucket car with a cardboard box”.

Lois O’Donohue, ATSIC’s chairwoman, admits that the Family Violence Intervention program had “teething problems”. But she says these have been addressed and that it is now running smoothly. In response to criticisms that ATSIC is not doing enough to tackle domestic violence, she stresses her organisation is not a substitute for mainstream agencies, including the police and state government domestic violence units. She says such agencies aren’t doing enough for Aboriginal women and children.

She also says ATSIC does not have sufficient funds to increase spending on programs to address domestic violence, which she nevertheless calls “our big shame”. She reveals that “at this stage, we don’t have a policy to fund Aboriginal women’s legal services, but we are conducting some research into (the need for) that”. Her prediction that “there will be a lot of opposition to that from (existing) Aboriginal legal services” is already proving prescient.

Atkinson claims ATSIC treats domestic violence as a single issue, when it is inseparable from a host of other problems such as alcoholism, lack of legal help and a history of dispossession that includes widespread rape of Aboriginal women by white men. Atkinson, who directed the Beyond Violence video, says: “What we have right across the country, are absolutely appalling levels of violence against Aboriginal women.” She makes the contentious claim that in remote, barely policed areas such as the Cape York Peninsula, Aboriginal women have died following severe beatings, but that their deaths have been put down to natural causes.

She says that in the Kimberley region in Western Australia, an Indigenous woman is 33 times more likely to die as a result of domestic violence than any other person in Australia. Similar figures have been quoted for the Northern Territory.

Palmer, who as a detective was involved in many homicides involving Aboriginal women (“a common experience for police officers right across the top end of Australia”), believes the abuse suffered by Indigenous women is “the sharp end of violence“. He includes in this definition severe bone fractures, and kickings and beatings that may go on for several hours. “The frequency as well as the violence itself is disturbing,” he says.

He started working the Territory 30 years ago, “before Aborigines had the right to drink per se”. He believes “there is no doubt that the infusion of drink has resulted in an escalation of violence against Aboriginal women which is out of all proportion to what I have seen elsewhere in society”.

It is of increasing public concern that Aboriginal legal aid services are so defendant-oriented they don’t represent Aboriginal women who present as victims of violence inflicted by their own men. This means battered Indigenous women are usually referred to a non-Aboriginal lawyer or service.

Audrey Bolger, a lecturer in social work from the University of Western Australia, conducted a year-long study of black women and violence in the Northern Territory in 1991 and declared: “The question that has to be asked is why a service which is for all Aboriginal people is operating in such a way as to disadvantage half the population? In fact, many people in legal aid are also concerned about this, particularly some women lawyers who find it horrific to have to defend a man in court when they have seen what he had done to another woman.”

Normally, it is considered unethical for the same legal firm to represent the complainant and defendant in any one case. However, Palmer says it is not unknown for an Aboriginal woman to find that a white lawyer from an Aboriginal legal aid service, in whom she has put her trust, is also defending the man who abused her. This and the fact that Aboriginal legal aid solicitors are defence lawyers “can work very actively against the interests of the victim,” he says.

But Chris Cunneen, a senior lecturer at Sydney University’s Institute of Criminology, believes Aboriginal legal aid services should not be “put down” for being defendant-oriented. He explains that roughly 20 years ago, the services grew out of a “racist administration of justice” whereby hundreds of Aborigines were processed through a court system with no representation. Most were men.

There continues to be pressure for Aboriginal women not to charge Aboriginal men with assault because it could result in the jailing of disadvantaged men, who have long been grossly over-represented in the nation’s prisons. Yet Aboriginal women also suffer disproportionately – and alarmingly – high imprisonment rates. According to Cunneen, black men comprise 28 per cent of all males in police custody, but black women comprise just under 50 per cent of all women in police custody.

Cunneen says imprisonment rates for Indigenous women are rising dramatically, that many are detained or jailed for minor offences such as drunkenness or fine defaults, and that some have been in prison for defending themselves against family violence. All of this, he says, “should be an issue demanding immediate investigation”.

Bolger, who is overseas on study leave, says that the legal hurdles facing Aboriginal women carry over into courtrooms. “Reading many court transcripts relating to cases of rape, murder and assaults on women is like reading the minutes of a male club,” her report says. “Judges, lawyers, and witnesses act to confirm each other’s prejudices … The interests of the victim are often completely forgotten in the efforts of all parties to find excuses for a man’s behaviour.”

She cites a case in 1988 in which an Aboriginal man had ruptured his wife’s spleen and caused two miscarriages. Yet he was described by a Northern Territory judge in his summing up as “a man of good character” with a good marriage. Though a Law Reform Commission inquiry into Aboriginal customary law in 1988 drew attention to the necessity of obtaining women’s as well as men’s opinions on traditional matters, several people, including Bolger, maintain there is little evidence this is happening in Northern Territory courts.

Jane Lloyd, an anthropologist and coordinator of a domestic violence project based in Alice Springs and reaching into remote areas, says courts and the police continue to cite customary law “all the time” in cases involving abused women, but “in a really irresponsible way”. She says it is sometimes mistakenly assumed Aborigines will resolve assaults within the community through their “payback” laws: “This is a really false assumption, because unless you have a really functional community that is really cohesive, paybacks do not happen.”

She and Kumbry Peipei, an Aboriginal project worker based at Mutitjulu (Ayers Rock), are particularly critical of the role being played by the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, which often represents black female victims of violence in the Northern Territory. They claim they “do it very, very poorly, if at all”. Lloyd and Peipei say a further problem militating against thorough presentation of battered women’s cases is that court interpreters are very rarely used.

A recent assault case in Queensland crystallises how legal procedures that take into account the disadvantages Aborigines suffer may also result in a double standard being imposed on the victim. In the case concerned, the Queensland Attorney-General, Dean Wells, ordered an appeal after a district court judge told an Aboriginal man who stabbed his de facto wife he might have been jailed if he was Anglo-Saxon.

The aggressor was put on probation and ordered to perform 120 hours of community service. No conviction was recorded. Ironically, the decision was praised by Aboriginal leaders from one Queensland community who interpreted it as recognition that Indigenous people have been disadvantaged by the law in the past. Among Wells’s grounds for appeal is the assertion that “the sentence is inadequate as a deterrent to violence against women”.

The debate about Indigenous women and violence was given a fillip late last year when an Aborigine, Robyn Kina, was freed from jail. The Queensland Court of Appeal set aside Kina’s conviction of murdering her former lover, having decided the legal system had failed her, as it had not allowed evidence that she had been raped and battered by him for several years before she killed him.

Violence awareness measures recently initiated by Aboriginal women include the first national domestic violence conference for Indigenous women, which was held recently in Brisbane. In Sydney, a group of women are attempting to set up a legal service for Aboriginal women and, to this end, have received $50,000 from the NSW Law Foundation and have put in a submission to ATSIC for further funding. There is interest in setting up an equivalent service in Queensland.

Though there are a few, if any, comprehensive programs aimed at tackling black family violence, in some areas black community police officers, nominated by Indigenous communities are receiving increasing recognition from police. Aboriginal women are rarely nominated, and this is proving a problem in domestic violence cases in which traditional women may think it taboo or feel too ashamed to discuss with any man details of the abuse that they have suffered.

An important legal reform undertaken in recent years means a police officer, rather than a victim (white or black) of domestic violence, can take out a restraining order against a violent man, leaving the victim less open to retribution. However, some social workers and lawyers complain that police offices in several states are reluctant to use these powers on behalf of Indigenous women or are unaware of them.

Judy Atkinson and Jane Lester adamant that solutions other than jailing Aboriginal man who abuse their families have to be found, partly because prison rarely has a rehabilitative effect on such offenders, who may return to their homes angrier than they left them.

Atkinson believes part of the long-term solution lies in reinstituting traditional mediation skills at a community level. She and Lester are both interested in community programs that encourage perpetrators and victims to analyse their own behaviours and to view them in the context of two centuries of racial oppression. Says Lester: “You cannot decrease the incidence of family violence in a few years, when it took so long to develop.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout