Review: MTC Turn of the Screw and Great Australian Speeches

Sarah Goodes’ Turn of the Screw — a four-and-a-half hour reading of Henry James’ creepy novella from the MTC audio lab — is a parable for our times

Is it strange that the Melbourne Theatre Company in this period of plague should concentrate its streaming efforts on its audio lab?

Not really in this era of podcasts where the spoken word has been reborn. What is noteworthy about the MTC’s audio ventures is that neither of the offerings are actually plays. Sarah Goodes, MTC’s associate artistic director, has put together a three-part, 4½-hour version of Henry James’s very creepy and subtle novella, The Turn of the Screw, and Petra Kalive has done a series of Great Australian Speeches in which the voices of Indigenous Australia are juxtaposed with memorable moments in mainstream — largely white and Anglo — history.

Does this leave us, in Hamlet’s phrase, with some necessary question of the play to be then considered? Well, yes and no. There’s no doubting the intrinsic drama of The Turn of the Screw. It is the story of a late Victorian governess who finds herself the custodian of a couple of young children, Miles and Flora, who appear to be in communion with two spirits from hell, a white-faced, red-haired charmer of damnation, Peter Quint, and his comrade in darkness, the former governess Miss Jessel. Our heroine sees these lurking malevolent apparitions and comes to realise that beautiful little Miles, this golden-haired angel of a child who has been expelled from school for nameless (are they unspeakable?) deeds and his sister, Flora, are in fact the innocent-seeming faces, so seductive in their beauty, of the deepest pit of a rampant iniquity satanic to its depths. James was an aficionado of the ghost story and he was also the first, and arguably the greatest, English language master of point-of-view writing — the domain of the unreliable narrator.

And the heroine of The Turn of the Screw is the unreliable narrator to die for. Are the ghosts real? Are the children malignant or is the whole diabolic mechanism simply in the governess’s head? Everything in the novella balances on a knife edge of ambiguity. And this makes it, if anything, creepier because we can’t disentangle the nightmares of madness the governess rides, from the spectral visions and the annihilating apprehension of evil.

Sarah Goodes has chosen a suggestive parable for our times in The Turn of the Screw because it is being presented by a number of actors’ voices at a time of bewildering anxiety. Who knows, who knows for sure, whether the measures being taken to minimise the COVID virus are the absolutely necessary safeguards of human life or whether they will just plunge the young of today into a pit of worldly insecurity, in an effective crippling depression economically, which is also likely to have the most dire consequences in terms of personal depression?

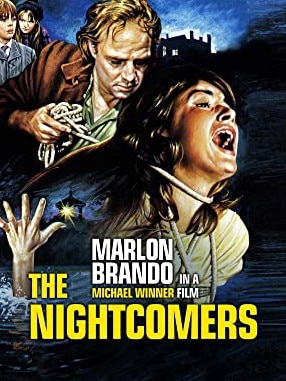

The Turn of the Screw was filmed as The Innocents in 1961 by Jack Clayton with Deborah Kerr as the governess, Michael Redgrave as the uncle and Peter Wyngarde as Peter Quint. And then, in 1971, as The Nightcomers by Michael Winner, with Anna Palk as the governess, Stephanie Beacham as Miss Jessel and Marlon Brando as Peter Quint. There’s a new one with Mackenzie Davis, The Turning, that’s had unenthusiastic reviews.

There are various spoken-word versions of the story; an Audible unabridged version by Emma Thompson and a Naxos abridged one by Emma Fielding. It can easily bear being cut and it has a diamond-sharp intensity. It is, potentially, an extraordinary lyrical aria of hysteria and heightened perception commingled for the solo — if virtuoso — actress’s voice.

You could do The Turn of the Screw in a tight, still subtle 70 minutes. The MTC version is uncut; it makes you grateful for the authority and gravity of Robert Menzies, who can read prose so well because he has a feeling for verse — a man who, in his day, could transfigure a stage as Shakespeare’s Pericles or Ibsen’s Peer Gynt. Rapidly, however, the production comes to be dominated by Katherine Tonkin as the governess. It doesn’t all together help that Tonkin plays the harrowed heroine in middle Australian and — for instance — actually says “In-compare-ably” rather than placing the emphasis correctly on the second syllable. She gets the words but not the electrifying lyricism of entranced fear that makes the governess such a whirlwind

The performance does grow; there is a stillness and clarity in Goodes’s direction and Clemence Williams’s sound design is minimal and unobtrusive. It is a tremendous boon to the production that Marg Downey is so able as Mrs Grose, sounding like an international actor of the first rank, accent immaterial. On the other hand, Laurence Boxhall as Miles is wrong because he sounds like a sulky adolescent whereas he should be a golden child, whose cherubic smile and playful skittishness become central to the horror story. Still, whatever its failings, we feel grateful to Goodes for exposing us to every last word of James’s hymn of horror. It still harrows the soul and would be best in 15-minute dips rather than an almost uninterrupted session.

Great Australian Speeches is a wholly different endeavour, though a striking one. It takes the voices of Indigenous Australia and Indigenous actors and places them in a kind of dialectic with the greatest hits of Australian public speech. So we get Jack Patten’s speech from 1938 read by Mark Coles Smith talking about how there is still slavery in an Australia where Indigenous women are forced to work for mere rations.

This is admirable and illuminating. It makes you think and ponder your own ignorance, and is more powerful for the fact the rhetoric of all these speeches is residually formal, and part of the stereotype of what white Australians have to confront is a reluctance to think of black Australians as having this kind of power to articulate. Sometimes the arrangement wins you over despite yourself as with the recital of poems by young Indigenous poet Ellen van Neerven by Leonie Whyman talking about the kind of white guy she’d be willing to poke a stick at. On the other hand, I was disconcerted to hear the name of the only person on the list I’ve had lunch with, Lowitja O’Donoghue, mispronounced.

But this is a collection that will illuminate in every way. We get Greg Stone delivering John Curtin’s declaration of war on the Japanese and it’s impressive to hear the tight rhetoric of righteous anger, the talk of an assassinating Hitler-like enemy dyeing the sea blood red and the way it mingles with restraint. Stone also does Ned Kelly’s Cameron letter and we get Menzies’s (grandfather of his actor namesake) appeal to the little people. But the great star is Downey. Whether articulating with great dignity the maiden speech of Dame Enid Lyons, first woman in the House of Reps, or speaking as Nellie Melba from the stage of Her Majesty’s in Melbourne, saying she won’t weep in farewell, she’s superb. How she brings alive the suffragette lady who says war is an abomination that confounds the Sermon on the Mount and Billy Hughes’s enthusiasm for conscription an iniquity. I wouldn’t have minded an actor, Menzies perhaps, capturing the eloquence of that turbulent priest, Daniel Mannix, on the same subject.

The Turn of the Screw parts 1-3 and Great Australian Speeches are available at mtc.com.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout