Booker prize: is The Mirror and The Light a true history?

Depicting history’s great heroes and villains through books, stage and screen can garner glittering prizes — does it matter if it’s all made up?

How staggering that Hilary Mantel, who began her saga of Thomas Cromwell and Henry VIII in Wolf Hall, should be on the long list of candidates for this year’s Booker Prize — announced in November — for The Mirror and The Light, the concluding volume of the trilogy. It shows a tremendous effort by Mantel to conquer the world of literature and an extraordinary passion to make history, and the shadow of history, a gateway to creating a popular success that is also some sort of artistic triumph.

History is a tricky business in the world of fiction-making, involving all sorts of tricks with mirrors and lights, which shine so bright they leave us blind.

And then there’s all the darkness of the past, the horrors we know, and the things we don’t know about.

Mantel’s three-volume Thomas Cromwell epic is, on the face of it, an improbable venture. Thomas Cromwell — not to be confused with Oliver, the Roundhead leader of the English Civil War who cut off the king’s head and established Britain as a Commonwealth — was Henry VIII’s hatchet man. Cromwell divested the church of its abbeys and monasteries in order to pay off the aristocracy as the new Anglican Church was established.

He undertook the prosecution of Sir Thomas More, the Lord Chancellor who wrote Utopia and who did not approve of Henry VIII taking a new wife, Anne Boleyn, and creating a new national church. More lives in history as some kind of saint and martyr, a great Christian humanist who became a reluctant hero. You can see the calm shining from the face of this friend of Erasmus in the great Holbein portrait in the Frick Museum in New York; in the face of Paul Scofield in his Oscar-winning performance in A Man For All Seasons, with the deep lines that suffering etched in it when he came to embrace his doom.

But, hold on, this is one image of More — and one Mantel in particular abhors. There is also the More who was the zealous persecutor of heretics (another name for Protestants). You can think of Cromwell as the murderous thug responsible for the mass executions of the unworldly Carthusian monks — or think of More as essentially an inquisitor, reinforcing a traditional, reactionary religious orthodoxy with the threat of the stake: with dungeon, fire, sword.

It’s pretty apparent Mantel, a lapsed Catholic, loathes the figure of More — so sympathetically presented in Robert Bolt’s play — and part of the sweeping revisionist drive of the Wolf Hall sequence (she won the Booker for that novel in 2009) is to present him as cold and cruel for all his high and mighty intelligence. Anton Lesser captures this in the 2015 BBC TV production of Wolf Hall with Mark Rylance as Cromwell and Claire Foy, the young queen-to-be in The Crown, as Anne Boleyn.

As for the real Thomas Cromwell, he looked much more like Leo McKern in A Man For All Seasons who played the role with a relentless razor-sharp — axe-sharp, indeed — shrewdness.

Mantel’s very long, expansive trilogy with its magnificently sustained simulation of a Tutor rhetoric — comparable to Robert Bolt’s dialogue but with an epical panoramic range as befits the highest fiction — is compatible with this while presenting the antihero in the most sympathetic light possible under the circumstances.

Cromwell was the henchman of Cardinal Wolsey, a veteran of Italian wars, a hardened professional in the senator Graham Richardson “Whatever It Takes” mode. You can shrink from the figure of Thomas Cromwell, and take a cool view of Mantel’s admiration of his brutal pragmatism, and still admire the reality she conjures up.

My own generation has a weakness for the individual driven to a lonely heroism in a dark time, which was a dramatic tendency during the Cold War and is there not only in A Man For All Seasons but another unforgettable costume drama, Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, where the witch hunts in Salem become an allegory of McCarthyism and the hounding of anyone who had ever been even remotely left-wing. It’s fascinating that Miller’s image of Salem, Massachusetts has become the dominant one in everyone’s historical imagination. History has to be imagined, vivid in the mind’s eye, if we are to have legends to live with.

Whether she wins the Booker again or not, Mantel has utterly resurrected the traditional bodice-and-breeches variety of trashy (ie, populist) historical fiction — and she has done so by transfiguring it, just as you could argue that Bolt and Miller transfigured the 1950s taste for costume drama spectaculars of which Stanley Kubrick’sSpartacuswas probably the most distinguished example

It’s interesting that one of Mantel’s greatest Australian fans, the late Inga Clendinnen, was such an enthusiast for Mantel’s nonfiction (which happens to be very fictionalised in technique) but hated the idea that historical fiction could ever teach us anything about the past. Clendinnen was a great historian of the Aztecs who went on to write a book-length essay about the Holocaust. She was relentless in her disdain for any truth-telling claims that could be made for a book like Kate Grenville’s The Secret River, which shows a “good” man coming to annihilate Aboriginals. A Room Made of Leaves — Grenville’s new historical novel about Mrs Macarthur, wife of early colonial grandee John McArthur — was published last month.

TS Eliot said “history may be freedom, history may be servitude”. Eliot also said Shakespeare got more history out of Plutarch than someone else could have got out of the British Museum. Plutarch, who wrote parallel lives of the Greeks and Romans and was remarkable for depicting the human characterisation of historical players, is Shakespeare’s source for Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra. It’s clear that in the description of Cleopatra, “the barge she sat in like a burnished throne / Burn’d on the water”, Shakespeare could not have written as he did without Plutarch in front of him. Yes, but in the great historical speeches of Julius Caesar — not just Marc Antony’s “Friends, Romans, countrymen” but Cassius’s “why man he doth bestride the narrow world / Like a colossus” or Brutus’s “It must by like his death” — we have the greatest empathetic recapitulation of the marbled way the Romans gave shape to their political utterances outside of the speeches of Cicero and the history of Tacitus. Shakespeare simply inhabits a Roman consciousness and what issues from his pen and captivates the mind with utterance of a Brando speaking as Antony over the body of Caesar, alone or before a multitude, is uncanny.

This kind of imaginative magic worked at a more modest level in the BBC’s 1970s I, Claudius — derived from Robert Graves’s novels using Roman historian Suetonius but excelling the novelistic original. Think of Derek Jacobi as the mild, stammering good guy,

Claudius; of Brian Blessed as a bluff middle-of-the-road Augustus; Sian Philipps as the beautiful and sinister empress, Livia; John Hurt at the height of his crazy powers incarnating Caligula. I, Claudius will live as a classic of what television can achieve and the mirror of history is integral to that. It is also true of the greatest portrayal of Queen Bess (greater than Bette Davis before her and Cate Blanchett after her): Glenda Jackson in all her savage glory and fury in Elizabeth R in the 1971 miniseries.

History and its interpretation are always a mystery, a surprise packet for the opening. And this can work too in the most dark and bewildering ways.

Last month Olivia de Havilland died at 104. Of course, she famously played Melanie in the now much abused most popular movie of all time, Gone With the Wind, and over a range of films in the late 30s and early 40s was the love interest of Errol Flynn: Maid Marian, for instance, to his Robin Hood. By the purest chance, when the news of de Havilland’s death came through I was watching The Santa Fe Trail, and she plays a woman Flynn falls for. The film, directed by Michael Curtiz (of Casablanca fame), is about John Brown, the abolitionist. Flynn played Jeb Stuart, one of the most dashing Confederate generals.

Most striking about The Santa Fe Trail was that it seemed to be all the bad things Gone With the Wind had been wrongly attacked for. John Brown — who inspired the song, “John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave but his soul goes marching on”, which became The Battle Hymn of the Republic — was represented as a crazy fanatic who triggered the Civil War by trafficking African-American slaves across state lines. The film suggests the states (Stuart was from Virginia) were best left to settle their slavery issues in their own time. The most villainous figure, played by Van Heflin, is obviously bad and is supporting Brown. He is duly expelled from the military academy by its commandant, Robert E Lee. It’s a weird period piece and flies in the face of the way a lot of fair-minded people think of the Confederate flag as the swastika of American history.

In fact the film shifts and turns a little and is not as anti-abolitionist as it first seems. There is a scene late in the piece where a Native American woman can tell the future and who recites in her own language, which de Havilland translates line after line, that the men grouped around her will all become mighty generals but they will all be bitter enemies.

The Santa Fe Trail plays on this notion of irreconcilable differences. Flynn’s Stuart says to Ronald Reagan’s Custer that wherever his compass goes it always ends up pointing north. Edmund Wilson’s Patriotic Gore — which Robert Hughes admitted to me was an influence on The Fatal Shore — is full of intensely vivid, by no means unsympathetic portraits of figures on both sides.

Shelby Foote’s great narrative history of the American Civil War was revered by my dear, dead friend, poet John Forbes — an unregenerate man of the left. And yet Forbes maintained Foote’s work was implicitly more sympathetic to the South.

When America became obsessed by the Civil War in the 1990s as a consequence of the great Ken Burns TV documentary, it was because of an overwhelming sense of the sorrow and pity of war. Young African-American men who worked in Manhattan bookstores would lead you up to Shelby Foote’s The Civil War: A Narrative and say, “This is the great one”.

Gertrude Stein said America was the oldest country on Earth because it had been living in the 20th century longer than anyone else. Read the entry on John Brown in Barry Jones’s Dictionary of Biography and you’ll find the old Labor intellectual describing Brown as a fanatic.

To do justice to the horror as well as the glory of history, we need the fanatics and we need the faces of evil, as well as the false accounts. It seems to be the case that Shakespeare’s Richard III was unfair to that monarch, reflecting a piece of Tudor propaganda by Thomas More, of all people.

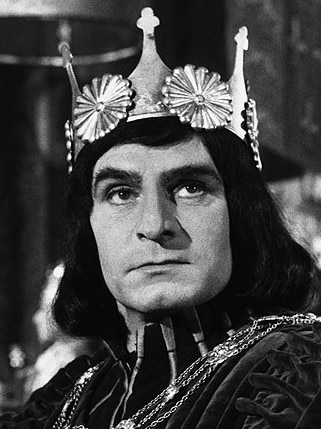

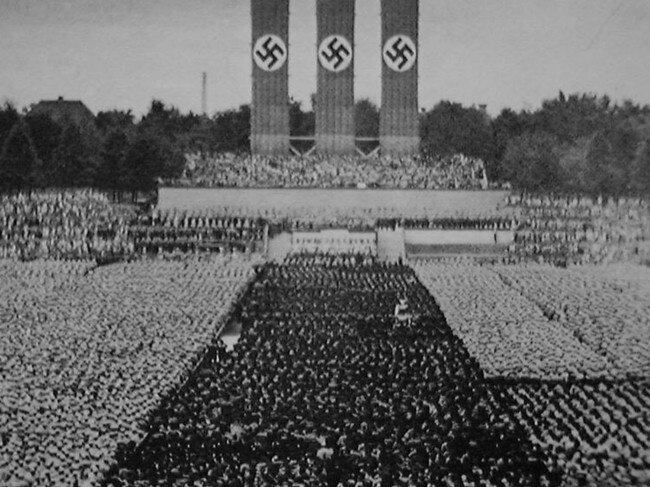

It hardly matters when we see Laurence Olivier’s 1955 film of the play because what we hear from the mouth of that bottled spider, that natural-born totalitarian dictator, is the absolute captivating stridency of a voice like that of the most sinister tyrant of all time, Adolf Hitler. People who speak German have noted the resemblance between Olivier’s shrill, clanging magic of a tenor voice that knows no pity and the voice of the man who could hold a Nuremberg rally in the palm of his hand.

Jewish people, indeed, who heard Hitler speak in Germany in the 1930s, testify to the power of that voice. Among German language actors, Klaus Kinski –– remember him in Aguirre? –– has something of that absolute unyielding metallic glitter.

There is no point in repressing the bravura of the Riefenstahl Nazi docos like Triumph of the Will and The Olympiad any more than there is in trying to destroy DW Griffith’s Birth of A Nation with its horrible sympathetic representation of the Ku Klux Klan conveyed with a mesmerising glamour. We need to acknowledge the power of the rhetoric as well as its poison. The greatest antidote to Riefenstahl is Alain Resnais’s very clinically cool survey of the remnants of Auschwitz.

That Frankfurt school thinker Theodor Adorno was wrong when he said “No poetry after Auschwitz”; after all, Paul Celan, one of the greatest 20th century poets wrote about it in poems about the camps such as, “Black milk of daybreak”. It’s not hard to understand how many people think the great documentary accounts of the Final Solution ––the film Shoah, and Primo Levi’s If This Is A Man ––are bound to be greater than any fictional representation. But Salo, the much-banned masterpiece of Pier Paolo Pasolini, has a terrible power in its depiction of fascism.

History is not an imaginary thing but the greatest history is imaginative. That is true after all of Thucydides’s History of the Peloponnesian War. It’s true of Gibbons’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Where does this leave Hilary Mantel? I’m not convinced by her history but in the last movement of The Mirror and the Light, when the King has turned against Cromwell, he becomes a deeply sympathetic figure, a victim of the world he has dominated.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout