A cultural history gone with the wind

Laughter and the ability to send things up is crucial to our sense of being human. And when we’re talking about history, we must remember the light, the shade, and the complexities.

Whatever you think of Gone With the Wind, it is one of the grander and more sumptuous pieces of entertainment Hollywood has perpetrated on the world.

Who could ever forget Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara or Clark Gable as Rhett Butler with his great closing line: “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.”

Does it matter that the old mammy, the faithful African-American retainer, is depicted in a way that looks a bit like Uncle Tomism? Not really, because we are not dealing with comprehensive visions of truth, and even when we are (as in great art and literature) we can’t expect them to tally with our utopian notions of the world.

The American civil war was conducted by the greatest of the Republican presidents, Abraham Lincoln –– a marked counterpart to his current Republican successor –– and it was fought on the Union side by figures such as Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman, who are among the inventors of the horrors of modern warfare. Grant systematically used his troops as cannon fodder, and Sherman famously declared: “War is hell. I remember nothing but the guns, the wounds and the groans.”

Their antagonist in the war was Robert E. Lee, who had been offered the command of the Union forces but said to the president: “I fear, sir, that I am a Virginian before I am an American.”

The African-American former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and head of the Pentagon, Colin Powell had on his wall Lee’s cautionary words: “It is well war is so terrible or we would grow too fond of it.”

Lee was universally revered by friend and foe alike, but these days he is liable to be reviled.

William Faulkner, one of the greatest southern writers, said of the past once, it should not only not be forgotten, it’s not even past — a remark that Barack Obama applauds in his memoirs. Are we going to go out and burn copies of Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury — one of the greater modern novels –– because we think the portrait of Dilsey, the warm-hearted black housekeeper who tends the Compsons’ children, reflects a tendency to keep African-American women in their place?

At a more popular level, are we supposed to forsake To Kill a Mockingbird because the publication of Harper Lee’s suppressed novel Go Set a Watchman makes Atticus Finch look like less of a cleanskin?

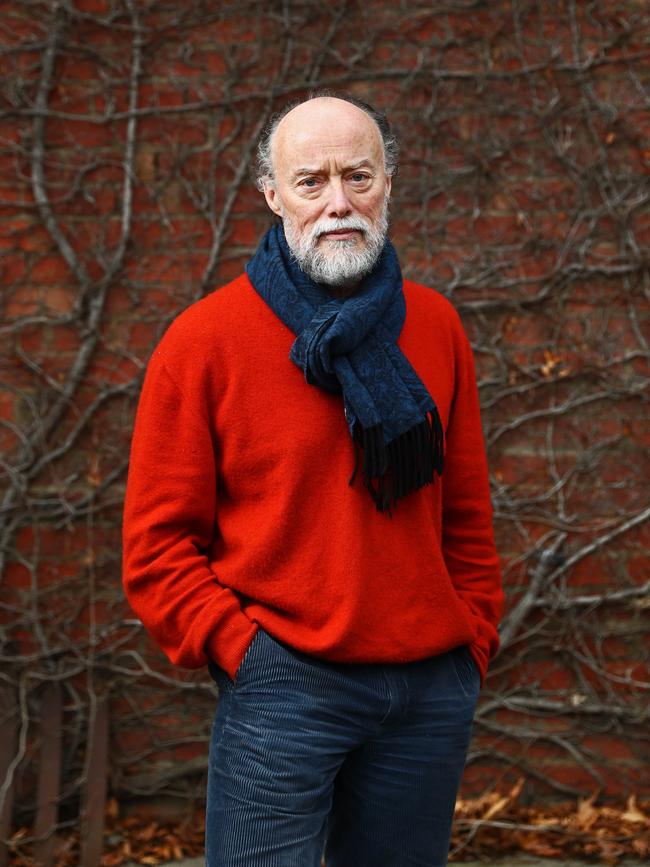

“My unapologetically low-key term for this,” Australia’s best known photographer Bill Henson says, “is fascist revisionism.” He is talking about the great wave of people calling for the history of the past to be done away with and derogated. Gone With the Wind supposedly dishonours African-Americans, James Cook was nothing but a despoiler and killer of Polynesians, and Sir Francis Drake was just spreading the dominion of slavery.

“There are lots of venerable examples of this in the past,” Henson says. “It’s like Pol Pot saying ‘back to the Year Zero’.”

Henson, at the height of his powers, was attacked by everyone from Kevin Rudd down because his photography (which is considered on par with great painting) depicted young girls. He’s appalled by the ignorance of the reaction against both the art and the policies of the past.

“It’s as bad as retrospective jealousy, where someone is in a new relationship and they start to ask about past lovers and come to resent them — that’s a form of madness,” says Henson, who is now in his 60s.

He blames the millennials. “It’s a narcissistic thing — if something hasn’t happened in the past couple of days, they don’t know about it. They are chock full of opinions but not information, whereas the greater someone’s learning is the less opinionated they are. When they know more, they are humbler in the face of history.”

He’s fascinated by the current movement to obliterate the past and the parallels with the history of China, the great power that’s on everyone’s minds at the moment, not least because of the coronavirus that originated there, as well as the backlash against Australia because we thought there should be an inquiry into it.

“When you read something like Pierre Ryckmans’s Chinese Shadows, you realise how much the Chinese live with their history and how much, from the successive imperial periods through, they can love their tyrants. Remember how during the Cultural Revolution, Mao said: ‘We must abolish the Four Olds: Old Customs, Old Culture, Old Habits and Old Ideas.’” He then cites Karl Marx on the way the first time something happens is tragedy, the second time is farce. Henson sees a parallel between this and today’s outrage where people on Rhodes scholarships at Oxford want to tear down statues of Cecil Rhodes: “Mao was certainly a precedent for these millennial tantrums.”

HBO’s knee-jerk reaction to pull Gone With the Wind leads to talk of the American civil war itself, which was fought over slavery. Henson wonders if the kids who are screaming have the faintest inkling of the massive loss of life in that war, rendered so starkly and poignantly in the great Ken Burns documentary TV series. “It becomes a form of collective forgetting,” he says.

He talks fondly of the work of the great archaeologist Osvald Siren and the vast magnificence of the Gates of Peking, so symbolic of the richness of a culture totalitarianism turned its back on.

He talks too of how different our own past was only yesterday. He mentions corporal punishment in passing as something everyone was once subject to. “People’s parents would think if a kid was strapped or caned at school, they would have done something wrong. Now a teacher would lose their job. And the parents of the millennials would be leading the charge.”

I’ve known Henson for a few decades now and his uncompromising loftiness about the importance of culture and history are the considered positions of a man of great gentleness and kindness who was forced to think about the politics of all this because he was so unfairly attacked. He’s at one with his dear friend Barry Humphries about the cant that can be involved in “woke” rhetoric.

It’s hard for any older person not to recoil in horror about the way the Black Lives Matter protests have somehow bled into a moment of cultural reaction that shows so little understanding of the difference of the past, even the recent past, and the way this is reflected in entertainment and art.

We have to know where to stop with all our vaunted pieties. Do we really want to lynch Chris Lilley because his portrait of Jonah Takalua sends up Pacific Islanders? Do we not cut him any slack because he also sends up private schoolgirls and gay music luvvies like Mr G? What on earth was Netflix doing when it pulled all four series of Lilley’s work yesterday? Comedy should be a test case. If you can’t tolerate comedy and satire –– if you really want to suppress Little Britain (or Monty Python, or Peter Cooke and Dudley Moore or the work of the late great John Clarke or Magda Szubanski) –– then you’ve lost all perspective on the reality of the world.

But laughter and the ability to send things up is crucial to our sense of being human, and no politics worth spitting at can afford to dispense with that.

And when we’re talking about history, it’s worth remembering the light, the shade, the complexities. Wasn’t it Winston Churchill who said when he heard of a guardsman having sex with some gent in Hyde Park in midwinter: “Doesn’t it make you proud to be British?” Churchill also said — and no, it wasn’t his finest hour — of Mohandas Gandhi that he was “a naked savage”. Gandhi, by the way, one of the greatest figures of modern history, said of Western civilisation that it was worth a try.

Does it matter that Churchill’s governments would have sent men to prison for homosexuality? Perhaps it does a bit, but history is not simple.

Barry Jones said once that Churchill was wrong about everything and that Clement Attlee (whose reformist Labour government introduced national health) was right but that only Churchill could have won the war and beaten Hitler. Historian Simon Schama tells the story of his old dad saying to him that he must never hear a word said against Churchill because, when no one else would stand up to the great enemy of the Jewish people, he did.

Let’s accept the complexity of human history and of human representation. Zhou Enlai was blackmailed into being the servant of Mao’s tyranny but he was one of the subtlest masters of diplomacy who lived.

The politics of Dostoevski were a form of Slavophile fascism that even Vladimir Putin would blanch at, but he was one of the greatest tragedians who lived. It was Vladimir Lenin who said of The Possessed, that masterpiece about terrorism that prophesied the dark side of Bolshevism, that it was “repellent but great”.

Lenin left the statue of Peter the Great, The Bronze Horseman, standing in the city of Leningrad for a while after it bore his name instead, and said beneath it: “Behold the tyrant.”

If you want to call people names, that seems a better policy.

Still, it’s a good bet to bear in mind that everything which enthrals us about the past — the greatness of Bach’s music, or Rembrandt’s painting, or Shakespeare’s dramatic poetry –– will reflect or connect with things that are bound to be radically imperfect. How could they not?

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout