Be it through politically correct conformity or sheer nerves in the face of a worldwide shaming on Twitter, broadcasters and publishers are nervously rifling through their back-catalogues to expunge any work with the capacity to offend.

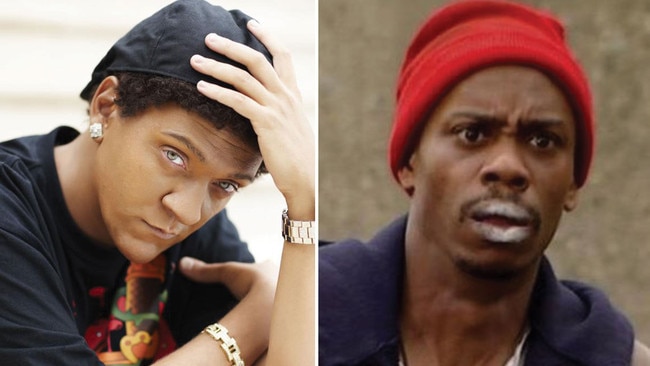

The manner in which Chris Lilley was dumped by Netflix is a case study in the speed with which artists can found themselves hounded with broadcasters now responding almost immediately by junking their entire body of work.

The comic value of Lilley’s work has always been contested, his detractors deriding him as an unfunny caricaturist, but in a society that ostensibly values free speech, the speed with which he was airbrushed from artistic history should unnerve any performer who lives on the edge, and any artist who deals with confronting material.

The tweets denouncing Lilley as a racist started this Tuesday, built to a crescendo on Wednesday, and as of today his work has officially vanished.

The question is: where does it all stop? If something as quaintly innocuous and dated as Gone With the Wind can be gone from HBO, what’s next?

Thinking back to my own childhood in the 1970s, and having a glance through my own book library and video collection, there are several works that might be for the high jump.

At the higher end of the spectrum, I wonder whether I might have to surrender my copy of Shelby Foote’s three-volume narrative The Civil War, daring as it does to humanise the young soldiers of the Confederacy and dispassionately credit its generals for their tactical skill.

Then there’s the old dog-eared copy of The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, in which the white author Thomas Kenneally dares to write in the voice of an indigenous man. That might raise eyebrows too, in the current climate.

What of Pulp Fiction?

From popular culture, what should we make of Quentin Tarantino’s classic Pulp Fiction? Sure, the movie might have highly-developed and intelligent black characters, played with mesmerising intensity by Samuel L Jackson as Jules Winnfield and Ving Rhames as Marsellus Wallace. But the final scene in which the protagonists must hide the slain corpse of a black man, amid an orgy of n-words from none other than Tarantino himself, might have this cinema classic heading for the discard pile. Given his association with Harvey Weinstein, Tarantino would probably be regarded as a deserving recipient of the new cancel culture anyway.

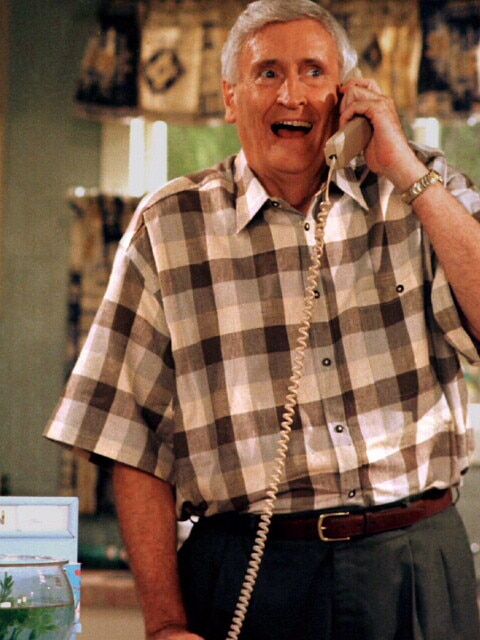

Kingswood Country a casualty?

At the lower end of the spectrum, I wonder if my parents can be retrospectively charged under the Racial Discrimination Act for letting me watch Kingswood Country, replete as it was with “wog” gags, and with Ted Bullpitt’s prized garden decoration being an indigenous man in statue form holding a spear, which he referred to as Neville the Concrete Aboriginal.

I am certainly not holding that program up as high art, nor willing the return of that kind of comedy, but making the point that these days it would almost be grounds for arrest.

Should we burn our Kevin Bloody Wilson and Rodney Rude LPs for their many crimes against good taste? Is Monty Python in the frame for transgender mockery through its penchant for transvestism, for ridiculing the French in The Holy Grail, for writing a song called I Like Chinese?

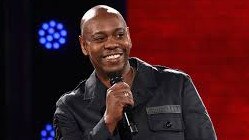

Things are getting so willing in the shutdown stakes that you could even imagine a scenario where black comedians get called out for racism, such as Dave Chappelle and his character Tyrone the Crackhead, a dishevelled and disoriented caricature of an Afro-American meth addict from the ghetto.

Also, do we judge the art, or do we judge the artist? Stan Getz was by all accounts a pig of a bloke, a drug and alcohol-addled wife-beater, who with Joao Gilberto and Charlie Byrd wrote some of the most sublime jazz music ever recorded. Is it time to start binning offending LPs from the record collection too?

Late last year I had the pleasure of interviewing Steve Martin and asked him about his wonderful movie The Jerk, in which he plays a simpleton named Navin Johnson, who despite being white is convinced he’s the natural-born child of a black family in impoverished Mississippi. Martin said he had never had any complaints about the movie because the black characters were the intelligent ones, whereas all the stupidity was owned by its white characters. In the current climate this feels less like a watertight defence, with the enthusiasm for shutting down any perceived offence resembling McCarthyism and the Salem Witch Trials rolled into one. The pressure is such that broadcasters such as Netflix and HBO think that it’s easier to go with the angry flow than tough it out, and remind people of the existence of the First Amendment.

More Coverage

The great cultural roundup of 2020 was ignited by an atrocity on the streets of Minneapolis and is now being driven by social media in an orgy of cancel-culture censoriousness that threatens lowbrow and highbrow culture alike.