Black Lives Matter doesn’t fit Australian context in a thin blue dividing line

Comparing indigenous Australians’ treatment by police to that of black Americans is unfair given reforms to our justice system.

The images were depressingly familiar. A lippy teen, a stressed cop, a senseless over-reaction. All of it captured on jerky phone-camera footage.

The vision of a NSW Police officer face-slamming a 16-year-old indigenous kid into the pavement of an inner-Sydney park seemed on the face of it to confirm what many in the Aboriginal Australian community have long believed: that indigenous people suffer disproportionately at the hand of the justice system.

The treatment of the boy, who for legal reasons cannot be named, came as the Black Lives Matter movement that has roiled American society arrived finally on Australia’s shores.

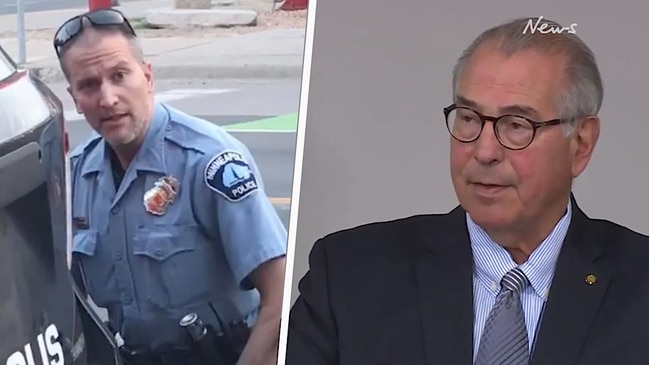

In Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, tens of thousands of people defied the threat of COVID-19 and took to the streets to protest, compelled by their conscience and a sense of outrage at the death of 46-year-old George Floyd, the African-American man killed during what should have been a low-octane encounter with police.

Floyd spent eight minutes and 46 seconds under the knee of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin before expiring from suffocation. His final words, “I can’t breathe”, have since become the anthem for a global protest movement spanning the cities of the US, Australia, Britain and Europe.

In Australia, outrage over Floyd’s death, concerns over police heavy-handedness and the intractable tragedy of indigenous disadvantage elided awkwardly into a single cause.

“It’s the same story on different soil,” 17-year-old Ky-ya Nicholson-Ward told a rally in Melbourne at the weekend.

But as well intentioned as the Black Lives Matter movement is, it sits uneasily in its Australian context.

The BLM protests are a uniquely American movement, born of the violent racial tensions that have long racked US civic life. Attempts to retrofit it to suit local conditions ignore the quantum improvements the Australian justice system has made in its treatment of indigenous Australians.

A movement is morphing

After days of protest and riots, the Black Lives Matter movement is morphing into a campaign to reform policing which demands reallocating funding from — and at its most extreme disbanding — police forces.

This week, the Democratic Party has proposed legislation designed to restore confidence in US law enforcement, including withholding of federal funds from local forces that do not reform.

While no one could dispute the dire state of indigenous Australians, it would be a mistake to lay blame for those problems at the feet of the police, the courts and the prison system. The shocking over-representation of Aborigines in Australian jails is the end-stage symptom of a problem the justice system is left to manage but did not create.

Data from the Australian Institute of Criminology shows that indigenous Australians are less likely to die in custody than non-indigenous Australians.

An AIC statistical bulletin published in February last year examined 393 indigenous deaths between 1991-92 and 2015-16. It found that most — 58 per cent — were from natural causes. The remainder were hanging (32 per cent) or drugs and alcohol. (5 per cent). Nine deaths, or 4 per cent of the total, were from what the AIC termed “external trauma”.

Further figures published by the AIC this year showed there had been 16 indigenous deaths in custody in 2017-18, accounting for 22 per cent of all deaths in custody. In 79 per cent of cases the cause of death was natural.

‘The death rate of indigenous prisoners was lower than the death rate for non-indigenous prisoners (0.14 and 0.18 per 100 respectively),” the AIC concludes.

“The death rate of indigenous prisoners has been consistently lower than that of non-indigenous prisoners since 2003–04.” The AIC also noted that since 2013-14 indigenous deaths in custody have increased.

Figures speak for themselves

None of this is to minimise the depth of indigenous disadvantage. The figures speak for themselves.

Aboriginal Australians make up less than 3 per cent of the population yet account for 28 per cent of all prisoners. Aboriginal women are the fastest growing category inside the corrections system.

Nor is it to deny that police brutality occurs, just as it occurs against non-indigenous offenders.

But in the years since the 1991 royal commission into black deaths in custody, the justice system has sensitised itself greatly to the vulnerabilities of indigenous Australians.

NSW Police Association president Scott Weber says police who arrest indigenous offenders are required to provide them with a lawyer, even if they don’t ask for one, must house them away from non-indigenous prisoners and check on them more frequently to reduce the risk of self-harm.

“Policing has changed over the (past) 20-30 years,” Weber tells The Australian. “There’s a lot more onerous requirements on police around oversight, diversions, drug courts.”

When they hit the courts, Aboriginal offenders draw a shorter average sentence than non-indigenous offenders.

‘We are not the US’

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the aggregate mean sentence for indigenous prisoners is 3.6 years compared with 5.7 years for non-indigenous prisoners. The average time expected to be served, a figure that takes in likely parole dates, has indigenous prisoners inside for 2.7 years compared with 4.3 years for non-indigenous.

“We are not the United States. We don’t have those systemic issues,” Weber says.

Looking at the crowds that swelled the streets of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane it is difficult to see them not as evidence of widespread police brutality but of the globalisation of modern protest movements.

Black Lives Matter, #MeToo and other post-millennial protest movements rocket around the world at lightning speed, thanks largely to social media.

According to Charles Sturt University professor of public ethics Clive Hamilton this is nothing new. Hamilton, whose book What Do We Want charted the history of protests movements in Australia, says while so-called hashtivism may appear to have changed the model for political activism, Australian protests movements have always been cosmopolitan.

“If we got back to the 60s and 70s, they, too, for the most part were very international,” Hamilton tells The Australian. “The anti-Vietnam War movement quite closely mirrored the movement in the US, often adopting the same terminology, like slogans ‘Hell no we won’t go’ and ‘Hey, hey LBJ how many kids have you killed today’.”

What has changed, Hamilton says, is the speed at which new ideas and new ideology takes hold, as well as the contemporaneous quality of the activism, which allows for hundreds of thousands of protesters to take to the streets at more or less the same time. He says the indigenous protest movement here in Australia has often borrowed heavily from the American experience.

He says the activists who set up the Tent Embassy on the lawns outside Old Parliament House in the 1970s styled themselves on the Black Power activists of the US.

“They gave clenched-fist salutes, they grew afros, they called for black power,” Hamilton says. “The Black Power movement had a very big influence on Australian indigenous activism.”

Hamilton says today’s social media-borne protests are like the older protest movements of the 60s and the 70s in so far as they must ultimately make contact with the real world to make a difference.

Campaigns that require a click or a “like” or an angry tweet run out of steam, he says.

“It’s only when they cross over (that) they bring real change, by going to the streets, targeting institutions or changing the way people vote,” Hamilton says.

“Online activism is really a catalyst but in itself rarely brings about significant change.”

Hamilton cites the #MeToo movement, a social-media juggernaut that became a potent force only after men began losing their jobs or facing police charges for sexually harassing or assaulting women — that is, once its consequences were felt in the real world.

Indigenous sceptics

Craig Somerville is an Aboriginal elder from Perth who was the chief executive of the Aboriginal Legal Service from 1985 to 1989. He agrees that Aboriginal Australians have borrowed heavily from the US.

“We’ve always had a strong synergy with black rights issues with the States,” he says.

“We adopted similar strategies — Charles Perkins, for instance, with the Freedom Rides. We had a sense that sort of movement had persuaded Americans and would persuade Australians.”

Somerville is sceptical of the view that across time the justice system has become more sensitive to the needs of indigenous Australians. He says while the messaging from governments, police commissioners and bureaucrats has changed, the situation on the ground remains the same.

“What was happening in the 70s and 80s is still happening,” Somerville says.

“We’ve still got deaths in custody, we’ve still got brutality on the ground. We’ve got a lack of understanding that has contributed to our situation.”

Indigenous elder Mary Aiken lives in Western Australia’s Fitzroy Crossing. She rejects the notion that police are heavy-handed in their treatment of indigenous kids. “They try their hardest to help them and direct them,” she tells The Australian.

“Parents up here, they allow the kids to roam the streets. I don’t see them heavy-handed in Fitzroy, The police are here trying to do their job and try to help the kids as well.”

Hamilton says that while Aboriginal activists have long modelled themselves on African-American movements, they bear more in common with Native Americans.

“But what matters is that there is sufficient similarity for it to spark a great deal of anguish in the indigenous community in Australia,” he says. “Isn’t that what really matters?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout