Sidney Nolan as you’ve never seen him: visual art review

Sidney Nolan’s interest in Greek mythology and experiences in the Great War deeply influenced his paintings

Myth is the earliest medium of human thinking about the world and our place in it; humans have told stories for thousands of years, while our capacity for self-critical reasoning is less than three thousand years old. And stories remain the simplest, as well as the most imaginatively evocative way of presenting ideas to the mind, which is why we teach children through stories rather than abstract principles, and why Christ taught his disciples in parables.

All bodies of mythology are interesting to anthropologists, but the myths of the Greeks are unique in achieving a far wider reach across cultures and through the centuries. They are incomparably more interesting than the Celtic and Germanic myths, for example, despite the efforts of some modern authors and composers like Wagner.

The Greek myths acquired their depth and resonance through the process of retelling and reshaping in art and literature over the course of centuries in a dynamic civilisation that was constantly evolving and reflecting on itself. And thus the myths themselves developed, grew more complex and acquired new layers of human and psychological meaning.

The process can be illustrated in one particularly rich family of stories. When Zeus, in the shape of a bull, carried off Europa to Crete to become the mother of Minos, her father, King Agenor of Phoenicia, sent her brother Cadmus to search for her. Failing to find his sister, he founded the city of Thebes, slaying a dragon that guarded the spring nearby and sowing its teeth in the earth.

Mythologically, this first ploughing of the earth symbolises the end of the golden age. Instead of being content to take what the earth offers us spontaneously, Cadmus kills the serpent that is her male consort, and assumes that role himself by inseminating her with teeth that, not surprisingly, bear a crop of armed soldiers; discord arises from the primal act of violence against the natural mother.

This ancient story speaks of the sense of transgression inherent in the very act that lies at the foundation of civilisation and of history itself: ploughing and cultivating the earth. But as it is retold over the centuries in a culture whose way of thinking is becoming both more rational and more self-aware, the story is extended into further generations, until we come to Cadmus’ descendant Oedipus, who kills his father and marries his mother.

Here the profound and dark mythological tale has been transformed into a psychological tragedy, almost entirely stripped of what we would consider supernatural aspects, except for the ambiguous role of the oracle of Apollo. But the tragedy of Oedipus still draws deep resonances from echoing the ancient myth of Cadmus, as Sophocles reminds us, especially at the climax of his play.

It is such an intuition about the deeper resonance of myth that led Sidney Nolan to find in the story of Leda and the swan – at first sight perhaps a surprising choice – a way of thinking about Gallipoli and war in general, as we see in Anthony Fitzpatrick’s fascinating exhibition at TarraWarra, with its many important loans from the estate of Lady Nolan (his second wife, Mary Boyd).

After the immediately post-war years during which he painted the Kelly series and had an affair with Sunday Reed, Nolan married Cynthia Reed and began to discover a wider world beyond Australia. He had had little formal education, but was curious, intelligent and intuitive, absorbing everything he saw and making it his own. He was particularly fascinated by the Greek sculptures and vase-paintings he saw at the British Museum and found the perfect guide to Greek mythology in Robert Graves’ recently-published Greek myths (1955).

One of the great merits of this book is that Graves cites all the ancient authors who are his sources and records the many variant versions of each story. Basic accounts of the myths – or even Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the main reference for Renaissance artists – can give us the impression that there was a single canonical version, when in reality there could be divergent or alternative ones in different regions of the Greek world and over the centuries.

Nolan went to Greece itself in 1955-56, visiting Athens and Delphi and then staying on the island of Hydra with George Johnston and Charmian Clift, both Australian authors. He became fascinated with the Trojan War and, like many young Australians who went to the Great War, could not fail to reflect on the proximity of Gallipoli to the ancient city of Troy.

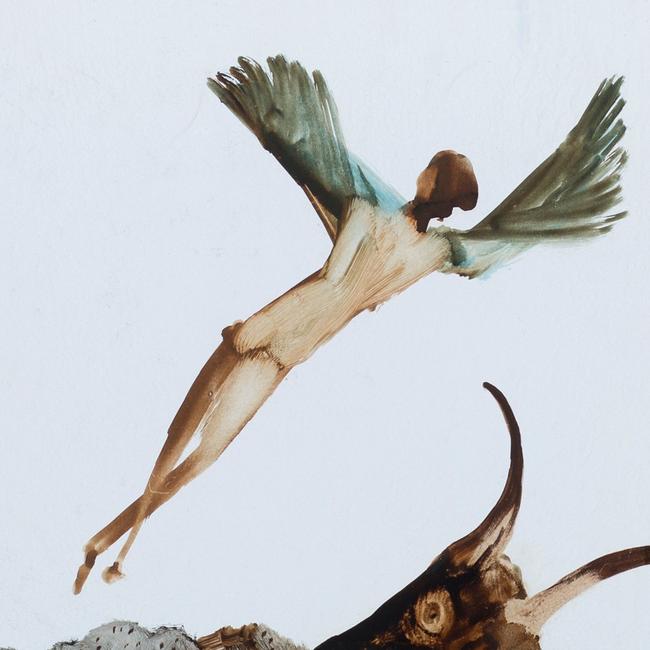

His early works on this theme evoke the fighting at Troy and are inspired by powerful and schematic battle scenes on Greek black-figure vases of the Archaic period. They are little more than stick-figures and reveal a characteristic combination of flair with limited skill and dexterity. Shortly afterwards, at the British School at Rome, he produced a set of often whimsical but also imaginative paintings on paper, clustered together here on one wall but shown at the BSR pinned to a folding screen, as we can see from a contemporary photograph.

Most of these pictures are of mythological figures such as Icarus or the Minotaur, already one of Picasso’s favourite images in the Vollard Suite. Several of the images, in fact, deal with theriomorphic figures of this kind which, in the predominantly anthropomorphic world of Greek mythology, always evoke the animal passions that are held in check, but never entirely suppressed, in the sane and balanced social individual.

As Nolan continued to meditate on this subject, we can feel him trying to combine mythological generality with historical particularity, closeness with distance and perspective. In fact he wrote, as we are reminded on one of the labels, “You need distance between you and a tragedy if you really want to show it in a dignified and truthful way.” Mythology gave him the distance; the fact that his younger brother had died during the war, albeit accidentally while on leave, gave him the personal connection to the tragedy of Gallipoli.

He also studied images of the campaign and was characteristically inspired by contemporary photographs of the Anzacs swimming in the sea as well as one of four naked soldiers riding their horses into the water. The idea of the riding figure – with its powerful animal associations – inspired several paintings, culminating in the one that has given its title to the exhibition, The Myth Rider (1958-59), which suggests both that the Anzacs were riding an immemorially ancient myth, and that the artist himself is a kind of horseman of mythic tradition.

The young naked soldiers swimming experienced, as Alan Moorehead writes, a kind of ecstatic pleasure compounded of the freshness and cleanness of water after the heat and grime, and the momentary sensation of pure freedom. But water also represents death, and the exhibition is haunted by often dark images of a dead body floating in shallow water. The most composed of all these figures, however, is not in the water but lying beside it: a homage to Poussin’s Narcissus, who lies wasting away by the edge of the pool.

Soldiers continue to appear in the later works inspired by Gallipoli, but it is the figure of Leda, who was already represented in the first series of sketches, who comes to dominate Nolan’s most ambitious paintings. Leda was the mother, by Zeus, of both Clytemnestra, who would later kill her husband Agamemnon, and Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world, who was given to the Trojan prince Paris by Aphrodite – although already married to Menelaus – thus provoking the Trojan War.

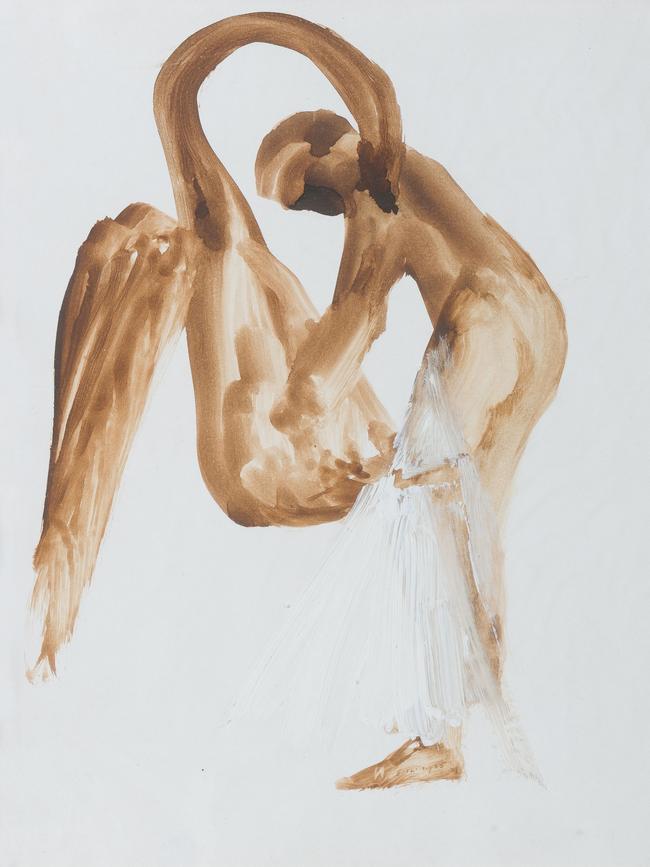

The myth of Leda – which is attested as early as the pseudo-Hesiodic Catalogue of Women – is thus a way for Nolan to gain additional imaginative distance, like stepping back from Oedipus to Cadmus to understand the full import of his tragedy. Her union with Zeus is mysterious and transgressive; it is by no means always imagined as a rape – in fact most ancient and modern artistic representations do not interpret in this way – but it is at least possible to imagine the god ravishing the girl against her will.

This ambiguity serves Nolan’s purposes well: the union is dark and fateful, and thus can be imagined as bearing the seeds of violence and horror; and yet it leaves room for the artist to meditate on it in different ways: as an act of violence, of perverse desire, of alienation or unconsciousness.

Nolan’s materials and method, typically idiosyncratic, are of course important in the expression of his subject matter. In the smaller works, he uses dyes on prepared paper, a strange, slippery medium that precludes clear drawing, modelling or the distinction between figure and ground. Everything seems to swim in the wet, oily texture, vivid but ineffable like a dream.

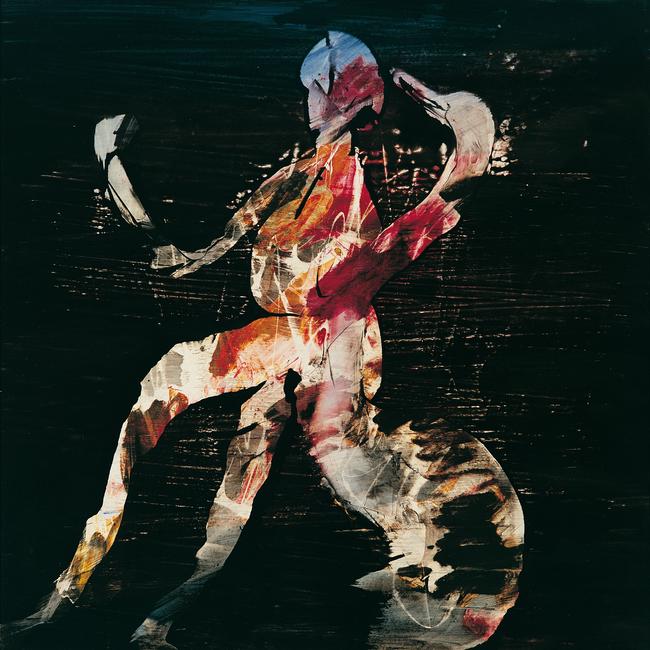

It is a dreamlike effect too that is evoked in a more lurid and vehement way in the large paintings executed in polyvinyl acetate paint. Cynthia Nolan left a vivid description, quoted in the exhibition, of the way he would paint these pictures on the floor, in layers of colour, ending with a thick surface that he would wipe back with a squeegee, creating the figures negatively, as in Degas’s black monoprints.

Depending on the layering of pigments before the final layer, which seems usually to be very dark, creating an intensely tenebristic background, the predominant colour scheme of the picture may be warm or cool, may suggest the bloodshed of war or the stasis and weightlessness of a body suspended underwater.

Nolan’s work does not represent one of the pinnacles of the art of painting; the paints he uses, and the methods he adopts are often clumsy and even ugly, but he was working at a difficult time, when the very possibility of painting the world, representing figures or telling stories was denied by the proponents of abstraction. It is to his credit that he refused to be cowed by fashion and strove to find a way to bring back figures and stories out of the very amorphousness of an almost abstract use of materials and even a process that alludes to that of Jackson Pollock.

The exhibition concludes with a coda by an artist whose name is rather fittingly Heather B. Swann. The work is apparently meant to act as some kind of contemporary feminist response to a male view of the story of Leda. In fact, Swann’s installation is mainly notable for its blandness. It does not come to grips with any of the possible interpretations of a subject that has such a rich history of representation by artists including Leonardo, Michelangelo, Correggio and many others. Her Leda has less agency than the woman in the ancient relief from Argos in the catalogue (p.29) or many renaissance prints; above all, the installation is an anticlimax after Nolan’s irresistible intensity.

Sidney Nolan: Myth Rider

TarraWarra Museum of Art, until March 6

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout