Ethel Carrick Fox’s painterly sensibility and poetic feeling anchor this exhibition

Ethel Carrick Fox and Anne Dangar, the two subjects of the National Gallery of Australia’s latest exhibition of women in art, are of a very different calibre.

The National Gallery has been accruing moral credits, at least within a certain cultural clique, from endless exhibitions about female and Indigenous artists. Most shows advertised on the gallery’s website fall into one of these categories – with the welcome exception of Masami Teraoka reviewed here recently, and a major exhibition planned for this year, Cezanne to Giacometti: Highlights from Museum Berggruen/Neue Nationalgalerie – and most of the faces advertising various lectures and talks and other activities are also female.

This increasingly prevalent feminisation of programs and exhibitions risks creating a gender imbalance as harmful as that of institutions without adequate female representation. One significant problem is the danger of exacerbating the perception in the world beyond the clique already mentioned, that “culture” is a field for women rather than for men.

Earlier last year, the gallery even proudly advertised a talk with an English woman who had written a book titled The Story of Art Without Men. It’s not hard to see that this would be about as enlightening as a history of science without men. And while it’s easy for supporters of such projects to puff themselves up with moral indignation at the alleged exclusion of women from the history of art and other higher spheres of human activity, they don’t ultimately do female artists any favours by implying that they can only become visible when all the more prominent male figures are removed. What we should really be looking for is a history of art that includes both men and women, each appreciated at their appropriate value.

The gallery currently has a pair of exhibitions devoted to female Australian artists, one of which is far more worthy than the other, which no doubt explains why they have been presented as a pair; the survey of Ethel Carrick Fox is substantial and interesting, and essentially props up the one devoted to the far slighter Anne Dangar. Unfortunately, the gallery insists on shortening Ethel Carrick Fox’s name to Ethel Carrick, dropping the name of her husband Emmanuel Phillips Fox.

Their claim (detailed on the exhibition website) that this reflects the artist’s wishes has in my view been debunked by the art dealer and valuer Leigh Capel, who conclusively demonstrates that more than 90 per cent of the paintings (in the exhibition) that she signed after her husband’s death were signed as Ethel Carrick Fox.

The relationship in art and life of Ethel Carrick Fox (1872-1952) and her husband Emmanuel Phillips Fox (1865-1915) was surveyed in an exhibition some years ago, Art, Love and Life, at the Queensland Art Gallery, in 2011 (reviewed here on Saturday July 30, 2011). They were, as I pointed out at the time, one of the few painter couples in the history of Australian art. He came from a distinguished Melbourne Australian legal family whose firm still continues today, and was enrolled at the National Gallery of Victoria from 1878 until 1886, when he left for Paris to continue his studies there, returning to Melbourne in 1891. He was a talented young man and had some excellent teachers in Paris, but was fortuitously absent from Australia during the critical years 1885-90 when Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton developed what became known as the Heidelberg School of painting. Phillips Fox never became part of this highly original Australian movement and remained instead an essentially derivative impressionist.

He ran a school in Melbourne during the 1890s, but by the end of the century he was longing to return to Europe, and was given the excuse by winning the commission to paint a history picture of the landing of Captain Cook at Botany Bay, which curiously enough required the winner to complete the painting in England. It was while working on studies at the beach in St Ives in Cornwall that he met Ethel Carrick in 1901; she had been born in England also to a wealthy family and had studied at the Slade School under the celebrated Henry Tonks. They were engaged in 1904 and married in 1905 although unfortunately the marriage remained childless, and after 10 years together, Phillips Fox died prematurely of cancer in 1915 while the couple were back in Australia.

Both Phillips Fox and Ethel Carrick Fox are significant but secondary figures in the history of Australian art. Carrick Fox’s style and her themes were limited and, as this exhibition confirms, repetitious, but they reveal a painterly sensibility and a poetic feeling that are seldom encountered today, barely taught in art schools and completely alien to everything that counts as official contemporary art. In other words, while the NGA celebrates Carrick Fox as a noted female painter of the past, it would never show any contemporary artist who worked in such a “conservative” manner.

Many of her most appealing pictures are very small and painted in oil on wood panel; the natural brown of the wood acts a mid-tone and a unifying ground to the pigments that she applies, just as artists of the baroque period like Caravaggio would start by painting their canvases in a brown imprimatura. This is all the more interesting in her case because her style is broadly impressionistic, and the impressionists tended to paint directly onto an uncoloured canvas.

Carrick Fox, on the other hand, not only paints on the natural ground of the timber panels, but deliberately allows this ground to show through, emphasising the “alla prima” spontaneity of her brushstrokes of relatively unmixed pigments. At the same time, this technical choice allows her to avoid what has always been one of the difficulties of oil paint, namely how to render edges, either where two adjacent bodies meet or when one is meant to stand in front of the other.

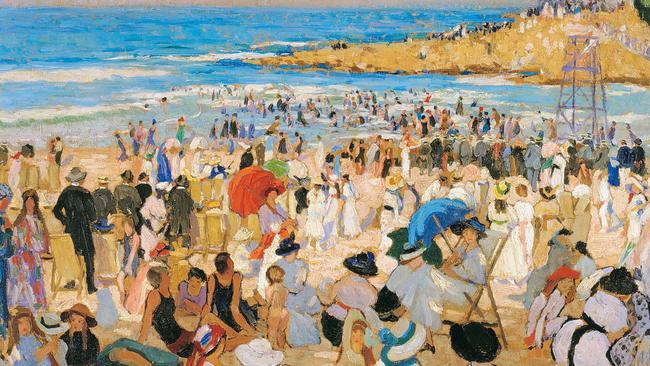

To take just one example, in Luxembourg Gardens (c. 1908) the statue on the left is surrounded in its lower part by a pinkish-ochre colour representing the sand or gravel of the park in the sunlight, but the dabs of paint do not meet the edge of the statue, leaving a margin of the underlying board to show through. Even in larger works on canvas like Christmas Day on Manly Beach (1913) she achieves the same effect – as can be clearly seen for example in the mother and daughter group on the lower right – by underpainting the canvas in a dark ground. And this stylistic device runs throughout her work; in two later North African street scenes, architectural forms are defined by the lines of unpainted board left to show through, allowing her to render the walls of these structures as flat areas of pigment, differentiated in hue and tone according to their illumination.

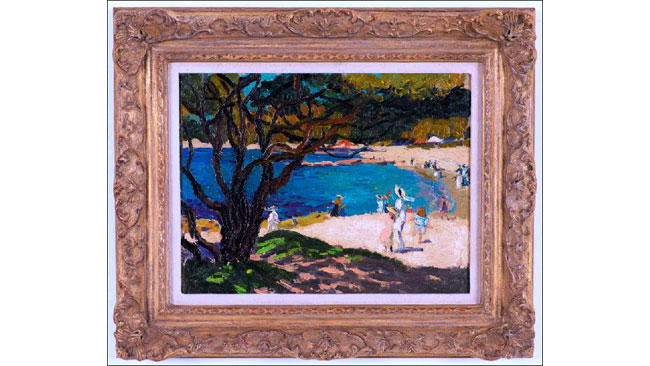

This is not to say that her pictures have no depth. On the contrary, she was evidently interested in effects of distance, including aerial perspective (in which objects in the distance become more muted in colour and less clearly distinct in tone, as well as smaller); but this is complicated in many of her pictures by a preference for views taken from a shaded foreground into a brightly lit middle distance – as in Christmas Day on Manly Beach and many other pictures, such as Watching the fleet from the Domain (1913).

The pictures are varied in location – she travelled widely both with her husband and later as a widow – but, as already mentioned, also repetitious in content. Apart from beach scenes – an interest she shared with Phillips Fox – Flower markets are a favourite subject; two of the best among many examples are French flower market (1909) and Flower market, Nice (c. 1926).Views of parks like the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris, especially when full of flowers, naturally overlap with the flower market subjects in visual effect.

These favourite scenes are predominantly animated by figures of women and children, not unexpectedly since flower markets are a quintessentially feminine location, and parks are often filled with children accompanied by mothers or nannies. But what is curious about Carrick Fox’s figures is that they are almost always anonymous and even faceless. She has a natural feel for the attitudes and movements of figure in action – as for example the young woman choosing flowers in Flower market, Nice – and yet the absence of facial features in the great majority of her pictures makes her figures feel sometimes disembodied, a shadow-play of costumes, curiously recalling her own family’s business in drapery and fashion.

As the artist herself declared, she was fascinated by crowds, and clearly more so than by individuals; perhaps this interest in a collective rather than particular sense of humanity can be related to her interest in Theosophy – a movement whose influence on modern art is often underestimated – from early in the 20th century at least, and especially after the death of her husband in 1915. Her pictures might thus be understood as evoking the flow of human life through and across time, especially in the endless cycles of motherhood and childhood, an impersonal and transhistorical cycle that underlies the incidents and dramas on the surface of historical unfolding.

There is an evident disproportion of achievement between Ethel Carrick Fox and Anne Dangar, to whom the NGA has attempted to give equal billing. Enormous hardback catalogues have been produced for both, a choice that speaks more of the political agenda of the gallery than of the substance of their subjects, but is particularly questionable in the case of Dangar.

Her story is certainly interesting, and was alluded to here recently in my review of the Grace Crowley and Ralph Balson exhibition at the NGV (August 11, 2024). She and Crowley were partners in the 1920s and travelled to Paris together in 1926, studying with the academic cubist Andre Lhote and attending his summer school at Mirmande, near Montelimar. They both subsequently studied with another late cubist, Albert Gleizes, in his art commune in the Rhone Valley.

In 1930, Crowley had to return to Australia to look after her sick mother, and they never saw each other again. Dangar stayed in France, enduring Nazi occupation during World War II; she converted to Catholicism towards the end of her life and was cared for in a local monastery before her death in 1951.

Dangar was an independent and intelligent woman, but she lacked a substantial practice. Her teachers in France were themselves minor artists, and it is sad to see her in the exhibition trying to follow in Gleizes’ mediocre footsteps. Worst of all, however, is that she ended up adopting the potter’s craft but was not in reality very good at it. She missed the renewal of ceramics as an art form led by Bernard Leach between the wars, when the modern studio pottery movement was born from a rediscovery of the great traditions of Japan, Korea and China. Dangar’s pots are not only vernacular in form but heavy-handed and clumsy; and their eclectic and rustic decorations do little to alleviate the impression of stolidity.

Ethel Carrick

Anne Dangar

National Gallery of Australia to April 27

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout