Victoria Amelina’s book on the Russian/Ukraine war lives on after her death

Victoria Amelina was bravely documenting the Russian war against Ukraine when a missile ended her life, but her story lives on in her posthumously released book

Reviewing a book by a friend who was killed before she had finished writing it is the saddest of tasks. Victoria Amelina, novelist, mother and all-round fun person to hang out with, died in July 2023, aged 37, after suffering grievous head injuries in a pizza restaurant in Kramatorsk, Ukraine, when it was hit by a Russian cruise missile. In the most tragic irony, her death was exactly the kind of case she was investigating in her new guise as a war crimes researcher.

As for all Ukrainians, the Russian invasion three years ago changed her life.

“We have to decide who we are during wartime,” she wrote.

Vika, as friends knew her, bought a gun and moved her 10-year-old son, Andriy, and white shepherd dog, Lyra, to safety in Poland. Then, despite describing herself as “a near-sighted bookworm”, she returned to Ukraine, and joined an organisation called Truth Hounds, interviewing victims and survivors of Russian attacks. On Twitter/X she pinned a picture of herself taking photos amid the destruction.

“It’s me in this picture,” she wrote. “I’m a Ukrainian writer. I have portraits of great Ukrainian poets on my bag. I look like I should be taking pictures of books, art and my little son, but I document Russia’s war crimes and listen to the sound of shelling, not poems.”

She was trained by a woman with the call sign Casanova, who drove around in a Mercedes van called Birdy. Over time, she became interested in other women documenting war crimes and conceived a book, which would follow such women, including Oleksandra Matviichuk, a human-rights activist who won the 2022 Nobel Peace prize; Evhenia Zakrevska, a lawyer turned frontline soldier; and Yulia, a librarian who helped uncover the murder of a children’s author.

I was introduced to Vika by a mutual friend, Emma Shercliff, who had become her agent. We quickly bonded over our shared interest in what war does to women, and became friends, meeting up in Kyiv and in London, which she visited in March 2023 to promote Ukrainian writers at the London Book Fair.

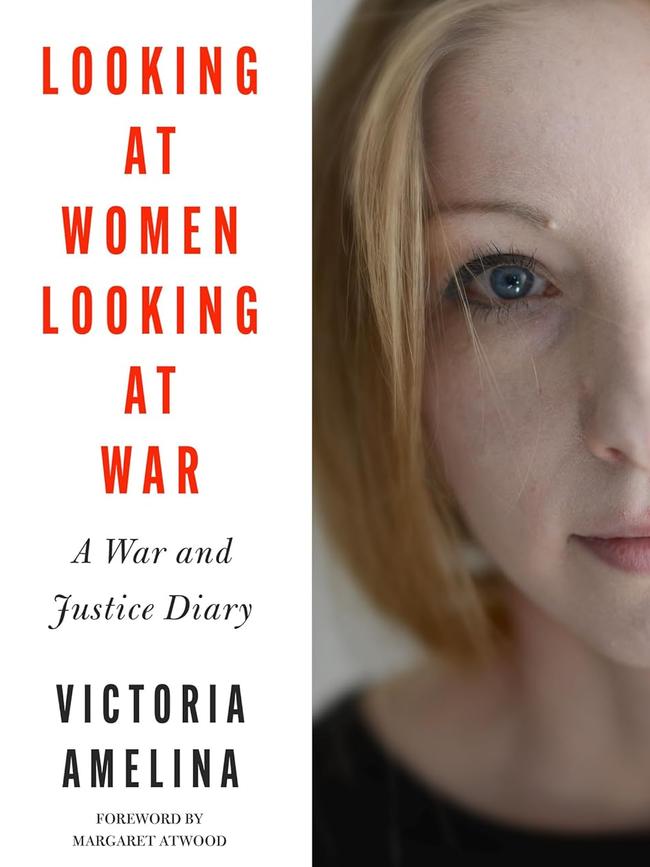

Watching her head off from restaurants in Kyiv to catch night trains to Kharkiv or Kherson, I worried about her. There was something otherworldly about this slight, pale figure with her earnest blue eyes and shock of strawberry blonde hair. Three weeks before she was killed she invited me for supper at her flat in a high-rise in Kyiv. “I have no cooking skills, but I have white wine and cheese,” she WhatsAppd me with smiley emojis. “And I have lovely views of Kyiv.”

I arrived to find a feast of olives, dolmas (rice wrapped in vine leaves), delicious Ukrainian cheeses and grapes. In the centre was a bunch of lavender in a vase that I realised was an artillery shell. “What can you do?” she said, laughing.

We talked about her book — she had just been awarded a fellowship in Paris, so was excited about moving there with her son and finishing the writing. Instead she went on one last trip, wanting to show some visiting writers from Colombia what was happening to her country, and going for that fatal pizza: 13 people were killed in that attack, including 14-year-old twin girls, and 64 were injured. Vika was taken to hospital but never came round.

The book was less than two thirds completed. Spookily, a couple of weeks earlier she had sent the unfinished manuscript to her friend Tetyana Teren with a note “just in case”. Teren, along with two other writer friends, Sasha and Yaryna, started piecing it together, helped by Vika’s widower, Alex, to whom she had also emailed voice notes and drafts.

This is the remarkable result. Not only does it tell the stories of some amazing women, it also chronicles Vika’s transformation from novelist and mother into war crimes investigator. In particular, how she uncovered the abduction and murder of the children’s author Volodymyr Vakulenko when his village was occupied by the Russians and found the diary he had kept buried under a cherry tree in his garden.

Sasha, Yaryna and Alex decided to keep intervention to a minimum, which makes for a visceral if sometimes truncated read. Much of the later part of the book is just fragments, drafts and notes she had left, along with footnotes explaining the process. There is also a lengthy interview she did with the human rights lawyer and writer Philippe Sands.

Some parts are so unfinished as to be confusing, yet in a way that is also its power because it highlights what the Russians have done. Nothing is a greater testament to the barbarity of this war than this book and life cut short. Vika is one of almost 200 Ukrainian writers and artists killed in the war. “The Tortured Poets Department (@Ukraine’s Version),” the Kyiv Government tweeted last April, referencing Taylor Swift’s latest album.

Determined to reveal the scale of the Russian atrocities to the world, she wrote in English using a form of documentary prose combining diary entries, witness accounts and historical references to show the Russian aggression against Ukraine did not start in 2022, and some poems. From the start her novelist’s eye is evident. We get descriptions of a rainbow appearing over the October Palace in Kyiv, the former torture chambers of the secret police and “origami angels swinging in the wind” made by children in memory of protesters massacred in the city in 2014.

Her voice comes across powerfully: gentle and direct, but also funny — just as she spoke. There is a hilarious account of being on holiday in Egypt with her son when the war started and being stranded, all airports to her country closed. She found herself quoting the poet Derek Walcott. “I guess when the world ends some people cry, some scream, some swear and others recite poems,” she writes. “To be honest I swear a lot too.”

Eventually, they found a flight to Prague, then a train to Poland, where she managed to get a lift across the border in one of just two cars crossing, taking a gas canister and a small souvenir bottle of Polish vodka bought at a petrol station. Everyone else was heading in the other direction.

“It seems like I’m going past my entire country that suddenly had to run for its life,” she writes. She describes crowds looking “like a giant moaning creature with hundreds of hands, mouths and eyes”. As she passed the line of cars, people, children and pets, which stretched for 25 miles, she took out her miniature bottle of vodka, and added: “Now I know what that was for.”

This book will make you laugh, cry and marvel at the resilience of Ukrainians. Nothing I or my colleagues can report will ever be this powerful. Amid the talk of peace deals, it is a reminder that everyone should read of the horror Vladimir Putin’s forces have inflicted and the bravery of those who stood up to them.

I am very happy for my friend that her book is coming out in 11 languages, but I always remember Vika bemoaning of Ukrainian writers that “it took a war and death for people to know our names”, and I am heartbroken that we will never be able to celebrate it together.