National Museum’s fine contribution to our fascination with ancient Egypt

An exhibition from the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, now at the National Museum of Australia, offers a more scholarly examination of ancient Egypt.

As the remarkable attendance figures for the Australian Museum’s Ramses exhibition testify – more than 350,000 – ancient Egypt has lost none of its fascination for contemporary Western audiences. In fact this fascination has been a characteristic of what we can broadly call Western culture from the very beginning: the Greeks already saw Egypt as an immemorially ancient civilisation whose origins were lost in a legendary past.

It is thanks to this interest that we have the first witness account of ancient Egypt written by the father of history, Herodotus, who travelled extensively in the country, observing everything from the topography to the daily customs of people whose lives were so surprisingly different from those of the Greeks.

His invaluable account of ancient Egypt is also evidence of one of the strengths of the Western tradition; contrary to what is implied by the facile expression Eurocentric, the West has been more curious about other peoples and more open to learning about and from them than most of humankind.

All peoples are culturally self-centred: tribal societies cannot even conceive of a different way of being and at more advanced stages of development societies tend to imagine their own model is superior, like the way the Chinese traditionally considered everyone outside the Middle Kingdom to be barbarians. It is not surprising if Europeans at various times have shared this sense of superiority characteristic of all higher civilisations, but what is notable is how often they have taken a deep interest in other civilisations. This was partly the inevitable consequence of the same energetic and outward-looking spirit that motivated the voyages of exploration and later the building of empires.

In any case the result is not only that it was Western explorers and navigators who mapped the whole surface of the globe but Western scholars who carried out fundamental research on all the languages of the world, as well as establishing the sciences of archaeology and anthropology.

Egyptology is of course no exception; from Herodotus 2500 years ago to the intellectuals of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, and finally the heroic age of Egyptology at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries, when the secret of the hieroglyphs was finally deciphered, this was an essentially European intellectual adventure. Today modern Egyptians are also playing a leading role in the archaeology of their country, although only the Copts are in fact descendants of the ancient Egyptian population.

The Ramses exhibition, as I mentioned in my review at the time, had an emphasis on spectacle, while Discovering Ancient Egypt, the exhibition at the National Museum in Canberra, which comes from the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, is more didactic and scholarly. It begins with the unique geography of Egypt which, as Herodotus memorably said, is “the gift of the Nile”.

Unlike other great rivers of the world, the Nile runs from south to north through otherwise arid desert, creating a border strip of fertile arable land through its annual floods. Herodotus reports a conversation with an Egyptian who was surprised to learn that in Greece water came down from the sky, for in his world it only came up from the river. The importance of the Nile only would have grown with the gradual rise in temperatures after the last ice age, which progressively reduced habitable lands in North Africa to barren deserts and probably drove populations to gather around the river, favouring the beginnings of settlement and civilisation.

The chronology of ancient Egypt is comparable in length to that of the other centres where civilisation first arose, in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley and the Yellow River in China. Between around 6000BC and 3100BC people were beginning to settle along the Nile and in its estuary, and to develop agriculture and the arts that followed from this fundamental discovery, like ceramics.

By 3100BC, upper (southern) and lower (northern) Egypt had been unified for the first time under King Narmer, at the beginning of the Bronze Age in what is known as the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3100BC-2545BC). It was also around this time that the Sumerians in Mesopotamia invented the first writing system – cuneiform – as well as the wheel, which revolutionised three important activities of civilised life: the transport of goods, the milling of wheat and the manufacture of ceramics.

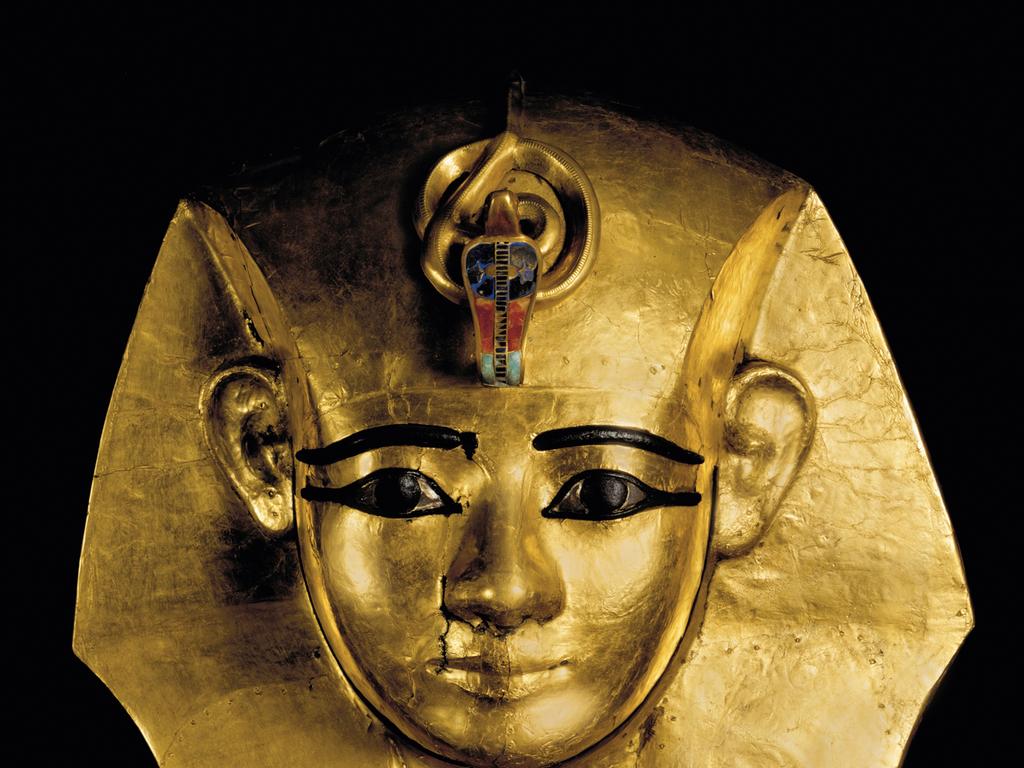

The Early Dynastic Period was followed by the Old Kingdom (c. 2543BC-2120BC), which produced the greatest and most enigmatic of all Egyptian monuments, the Pyramids of Giza, edifices that have haunted the West since antiquity. At the end of his third book of Odes, for example (23BC), Horace boasts that he has erected a literary monument “more durable than bronze, taller than the royal site of the pyramids”. A few years later, another Roman, Gaius Cestius, decided to mark his own tomb with a miniature pyramid that still stands just outside the Porta San Paolo. Above all, these royal tombs built to protect the mortal remains of the pharaohs attest to the paramount importance the Egyptians attached to the afterlife, in contrast to other ancient people such as the Minoans, who seem to have been much more focused on the earthly realm. Recent archaeological research, published only in the past few weeks, has shown that a branch of the Nile flowed very close to the site of the pyramids at the time; without access to water transport such constructions would have been impossible.

The Old Kingdom was followed by a series of major periods in which Egypt was ruled by a central government, and intermediate periods in which the country was divided between different and competing dynasties: thus the First Intermediate Period (c. 2118BC-1980BC) was followed by the Middle Kingdom (c. 1980BC-1760BC) – often considered a golden age of ancient Egyptian civilisation and contemporary with the apogee of Minoan civilisation in Crete. The Second Intermediate Period (c. 1759BC-1539BC) more or less coincides with the rise of the Mycenaeans in Greece. The New Kingdom (c. 1539BC-1077BC) is the period to which Ramses II belonged; it marked the triumph of Mycenaean culture in Greece (including the conquest of Crete) and Ramses was a contemporary of the Trojan War; soon afterwards the crisis of the Bronze Age civilisation, perhaps in part brought on by environmental causes such as a prolonged drought, and accompanied by the invasions of barbarian peoples armed with iron weapons, led to four centuries of Dark Ages in Greece and the Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (c. 1076BC-723BC). The end of this period, in the eighth century BC, coincided with the lifetime of Homer and the migrations of the Greeks westward, establishing colonies in Sicily and southern Italy.

Egypt was dominated by foreign powers in the ensuing Late Period (c. 722BC-332BC), first invaded by the Assyrians and then becoming part of the Persian Empire until its conquest by Alexander the Great, inaugurating 300 years of Greek Hellenistic rule, ending with the reign of Cleopatra. Her death marked the beginning of the Roman period, which in turn lasted until the end of the fourth century AD.

This exhibition is full of items illustrating the development of Egyptian civilisation, which was generally characterised by an extreme conservatism and the repetition of highly refined and stylised formal canons for centuries or even millennia – in contrast with Greek art, which even in the comparatively conventional Archaic period expressed a constant and restless quest for innovation. In the last millennium of Egyptian art, on the other hand, there is an increasingly obvious formal syncretism with Hellenistic styles, visible for example in a very late statue of Isis.

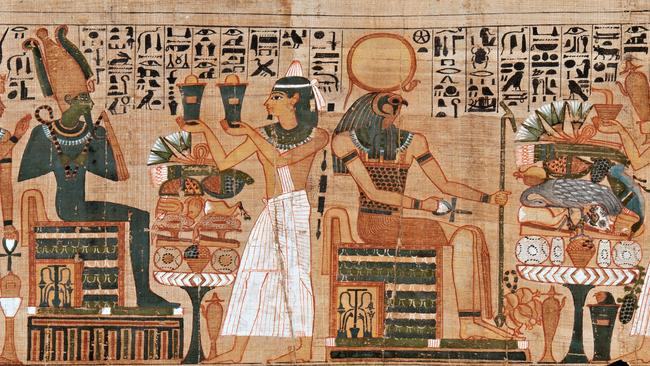

One of the most interesting sections in this exhibition presents a series of manuscripts and clearly explains the difference between formal hieroglyphs – whose translation was discussed in my earlier review of the Ramses exhibition (The Weekend Australian Review, April 13-14) – and the cursive hieratic script used in written documents, as well as the even more informal demotic script. Writing was done with reed pens on papyrus, which was in fact the main writing material throughout the Greco-Roman world as well. Later manuscripts are written in Coptic, an alphabetic script derived from Greek and adapted for the ancient Egyptian language.

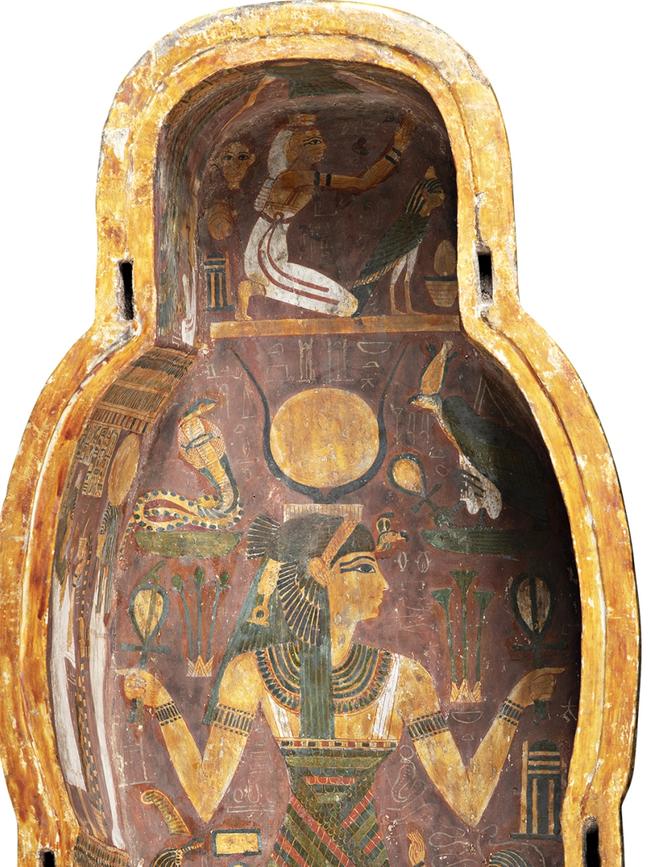

There are some fine sarcophaguses, including the inner coffin of Amenhotep, high priest of Amun at Thebes, from the 21st dynasty, at the beginning of the Third Intermediate Period, and the inner “mummy cover” that was laid over the wrapped body inside the inner coffin.

It may be fortuitous, but the face of Amenhotep on the coffin lid seems a little more confident and outward-looking, while his features on the mummy cover seem younger, more guileless, as though focused on another world altogether. Here too, the displays have a scholarly and didactic focus, such as a useful diagram that explains the system of outer, middle and inner coffins, as well as the mummy cover. Cartonnage coffins, used in the later periods, are explained too, as well as the iconography that was used to protect the dead body. The tools used for mummification are also exhibited, accompanied by a description of the process.

Actual mummies are visible in a special room, accompanied in these hypersensitive days by a warning in case viewers may be disturbed by the sight of human remains, and even more bizarrely by a label informing us that these bodies were “welcomed to the National Museum of Australia by local traditional custodians”. It is unclear what an aristocratic member of a highly sophisticated ancient civilisation might have made of such a ceremony, but it’s unlikely he would have considered this “welcome” as relevant or appropriate.

Equally interesting are the sections of the exhibition dealing with the modern Western interest in Egypt. We learn, for example, of a Dutch merchant who was based in Aleppo in Syria in the early 17th century and who acquired a mummy and other Egyptian material that he donated to Leiden University. As mentioned before, this was a period of great interest in Egypt, when Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher attempted to decipher the hieroglyphs, and long before the renewed impetus given to Egyptology by Napoleon’s campaigns in Egypt at the end of the following century.

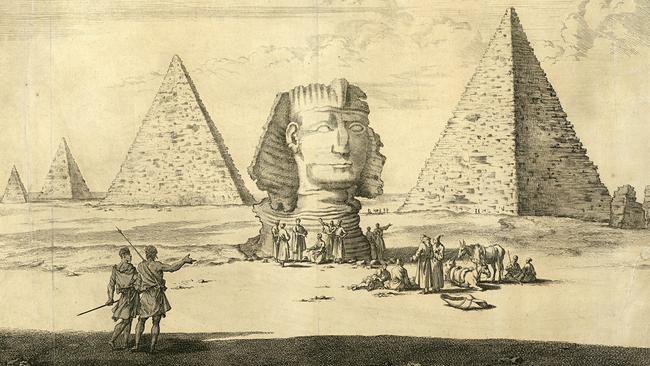

Among more recent documents is a fascinating engraving of the Sphinx based on a drawing made in 1681 by Dutch artist Cornelis de Bruyn and published in 1698. This was probably the first illustration of the Sphinx in modern art, but just as remarkable is a photography by Maxime du Camp, taken about 1850 when he was travelling in Egypt with the great French novelist Gustave Flaubert. For four millennia she has been gazing impassively into the distance, gradually weathered by the sun, the sand and the winds, and in an instant her image is fixed in a medium invented only a decade earlier.

Discovering Ancient Egypt

National Museum of Australia to September 8

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout