Ramses exhibition an important and well executed show

This is a big year for Egyptology in Australia, with three major exhibitions gracing our shores. The Australia Museum’s show on Ramses is a big-hit highlight

This is a big year for Egyptology in Australia, marked by three important exhibitions which, between them, run for almost a whole year (November 2023 to October 2024) in three cities. The first of these is the spectacular Ramses exhibition at the Australian Museum; the second is the more didactic Discovering Ancient Egypt, from the Dutch Museum of Antiquities at the National Museum of Australia – which will be discussed separately in some weeks – and the third is Pharaoh, from the British Museum, which will open at the National Gallery of Victoria in June.

Egypt has always fascinated the west, from the time of the Greeks, who saw it as an immemorially old civilisation and a repository of ancient and recondite wisdom, which at the same time presented many surprising contrasts with their own culture and habits. The first eyewitness account of ancient Egypt was in fact written by Herodotus in the middle of the 5th century BC. The whole of Book II of his famous History is devoted to the results of his personal research in the country and among the people, and includes everything from an account of the geography of the land he famously described as “the gift of the Nile” to explanations of the process of mummification.

The immediate reason for this sudden surge in interest in Australia, however, is undoubtedly a significant anniversary: it is just over 200 years since the hieroglyphic writing of ancient Egypt was first deciphered and its inscriptions, whether sacred, administrative or even literary, could finally be read. Although research into Egyptian texts and the grammar of the language went on for many years afterwards, the conventional date of decipherment is considered to be September 27, 1822, when Champollion’s letter outlining his initial discoveries was first read to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in Paris.

The British Museum, indeed, mounted an important exhibition over the northern winter of 2022-23, Hieroglyphics: unlocking ancient Egypt, whose catalogue offers a thorough and fascinating account of the long and complicated history of attempts to read hieroglyphic inscriptions, as well as the later Hieratic and Demotic scripts. There is also much useful material on the Museum site under “Past Exhibitions”, including a timeline of the history of hieroglyphs and their study both before and after 1822.

Hieroglyphic texts have been publicly displayed in Rome for some two millennia: the 13 ancient obelisks that punctuate the city today, marking the centre of squares and the ends of long vistas, were almost all brought from Egypt by the emperors. All eventually toppled over in earthquakes and most were re-erected by the popes in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The first of these was the Flaminio obelisk in the Piazza del Popolo, brought to Rome by Augustus in 10BC and placed in the Circus Maximus; a millennium and a half later it was discovered, repaired and re-erected in its present location by Pope Sixtus V in 1589. This spectacular engineering feat (the obelisk weighed 327 tons) was celebrated in a folio publication, including diagrams of the machinery used, by the architect Domenico Fontana in 1590. The Montecitorio obelisk was brought to Rome by Augustus at the same time to serve as the gnomon of a colossal sundial in the Campus Martius.

Hieroglyphs were thus prominent and tantalising, and considering the reputation of Egypt as the repository of esoteric knowledge, it was inevitable that Renaissance philosophers, in their quest for the lost wisdom of antiquity, would imagine that the Egyptian inscriptions concealed arcane and mystical knowledge. Their intriguing but impenetrable pictographic imagery influenced the Renaissance passion for emblems, visually pithy symbolic images that were designed to convey a complex set of ideas at a glance.

The Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher, in the 17th century, wrote extensively on hieroglyphs and believed he had deciphered them; this claim is often cited rather derisively, but as the British Museum makes clear, Kircher had made progress in certain areas, particularly in realising that some signs were to be interpreted phonetically, as well as in recognising that Coptic, of which he published the first grammar, was the last stage of the Egyptian language.

Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798-99 inaugurated a new era in Egyptology, and the Neoclassical style was strongly influenced for a time by Egyptian designs. In 1799 his soldiers made a crucial but random discovery: a stone stele – today known as the Rosetta stone – inscribed with what was evidently the same text in Greek, the official language of government, hieroglyphics, the ancient sacred language, and the more recent and vernacular Demotic script. It was this invaluable document that allowed Champollion, Young and other scholars to break the hieroglyphic code at last.

There have several other episodes in modern Egyptology that have captured the imagination of the general public. First was Howard Carter’s discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen in 1922; the death soon afterwards of Lord Carnarvon and others led to the popular myth of the “mummy’s curse”. The next episode that enthralled an audience far beyond the world of scholarship was the moving of the temples of Abu Simbel from 1964 to 1968. An entire complex including a set of colossal statues carved from the living rock was cut into sections and reinstalled on higher ground when the area was to be flooded to create the giant Aswan Dam.

It is the pharaoh who was celebrated at Abu Simbel who is the subject of the present exhibition, which comes from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and is conceived as a theatrical experience. This is much more of a spectacle than the Dutch exhibition in Canberra, as I have already suggested, but it is undeniably effective on the whole, and the “immersive” elements are generally relevant and specific, for example when they reproduce the wall paintings of tombs.

Ramses II (1303-1213 BC) who ruled for 66 years and died at age 90 or 91, was one of the greatest rulers in the history of Egypt, although he came relatively late in the immensely long history of the Egyptian civilisation, which was already some 3000 years old at the time of Alexander’s conquest, and continued under Greek, Roman and Byzantine rule until it was finally overwhelmed by the Arab invasions of the 7th century AD.

Ramses was a contemporary of the great Mycenaean king Agamemnon and of the Trojan War. These were the last generations of the Bronze Age civilisations before the crisis that would ensue from around 1200BC. He was also the pharaoh referred to in Exodus, under whom Moses led the people of Israel out of the Egyptian captivity and into the Promised Land.

Egypt had trade relations with the Mycenaean world, where Greek power had supplanted that of the Minoans for some centuries already, and it is mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey, where Menelaus in Book IV is becalmed on the island of Pharos, opposite the future city of Alexandria. Ramses’ most important military foes, however, were another Indo-European people, the Hittites who had settled in Anatolia soon after 2000BC.

Ramses’ decisive confrontation with them was at the Battle of Kadesh around 1274BC. The Egyptians were forced to join battle in unfavourable circumstances, outnumbered by the enemy. Nonetheless, according to the story presented here and indeed to Ramses’ own account in inscriptions, he won an overwhelming victory and personally slaughtered many of the Hittites. In other accounts the outcome was less decisive, but it did lead to a settlement with the Hittites that ensured decades of peace and stability.

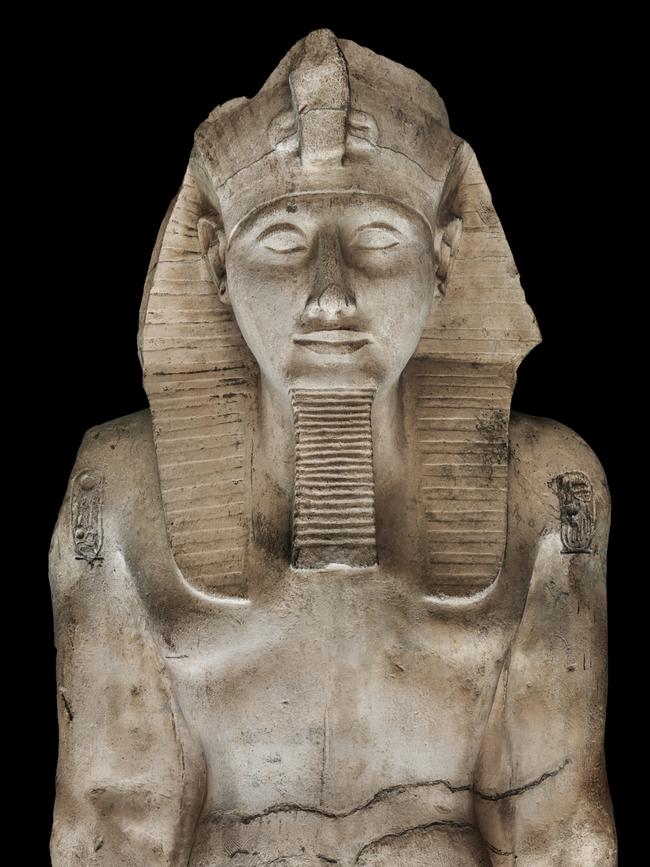

An entrance corridor brings us face-to-face with a monumental portrait of the king in red granite; or at least it purports to be a portrait of the king but is in fact an older sculpture that has been reappropriated. Nonetheless it is an extremely impressive work that displays not only the extraordinary skill of the sculptors who carved this extremely hard stone with bronze chisels but also the unique combination of religious and political culture in which an effigy of royal power is also a serene image of transcendent divinity.

Inside the exhibition are many other sculptures, reliefs and inscriptions of very fine quality. One of the most evocative is what we might think of as a limestone relief, only the figures are not actually carved in relief; they are rather engraved into the flat surface of the slab, so that the main figures are marked out by deep lines of shadow, particularly noticeable if looked at from one side.

This relief is an elaborate version of a standard iconographic motif which goes back to the Palette of Narmer, the monarch who unified Upper and Lower Egypt perhaps around 3100BC. Just as Narmer is shown smiting a kneeling enemy with a club, almost two millennia later Ramses, too, is depicted in the same posture, only now holding by the hair a whole group of defeated barbarians with vivid and picturesquely varied ethnic characteristics.

Among the most impressive objects in the exhibition are of course the sarcophaguses, including outer coffins, inner coffins and coffin covers that were laid over the wrapped and mummified body inside the inner coffin. All of these are covered with beautiful and elaborate paintings of the sacred figures who rule over the world of the afterlife, and are meant to act as protective charms to help the dead travel safely into and survive in the afterlife.

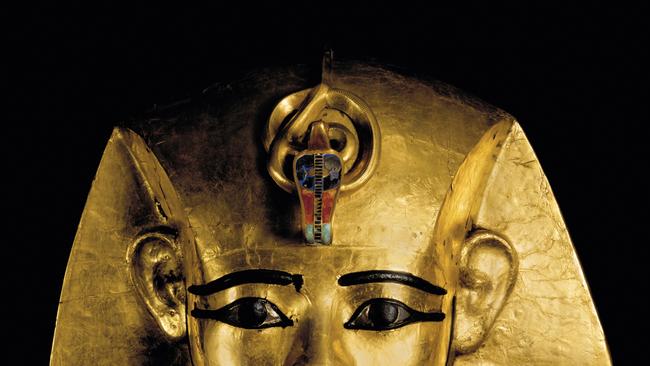

The most striking piece of all is, not surprisingly, the plain but exquisitely carved inner sarcophagus of Ramses himself. Its survival is something of a miracle, for even this great monarch’s tomb was attacked by grave robbers; fortunately his coffin, along with many others, was saved by priests who secreted it in a mountain cave that was not discovered until the 19th century. There was no doubt of its identity, for apart from its royal iconography, it is inscribed with the Pharaoh’s name and with the story of how it was rescued.

Gazing today at these serene and perfectly youthful features, it is hard not to reflect that the king was over 90 years old at the time of his death, and a computer simulation at the end of the exhibition attempts to reconstitute his appearance in youth, maturity and age from the desiccated skull of the mummy.

His youthful appearance in the sarcophagus portrait is no doubt not meant to deny that Ramses grew older with the passing of the decades; it is in part a kind of magic, endowing him with perfect youth and beauty for the eternal life that awaits him, while at the same time reminding us that, as a living god, Ramses was in a sense only superficially subject to the same processes of age as other mortals, and that in his essence, he remained forever young and vital.

Ramses and the gold of the pharaohs

Australian Museum to May 19

Hieroglyphs: unlocking ancient Egypt

British Museum Press, 2022

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout