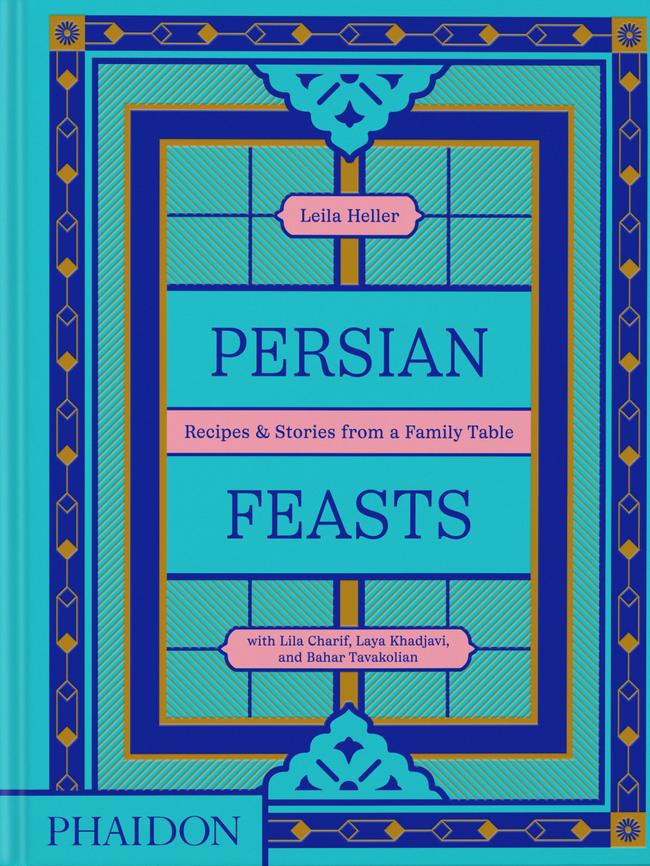

Persian feasts: a new cookbook review

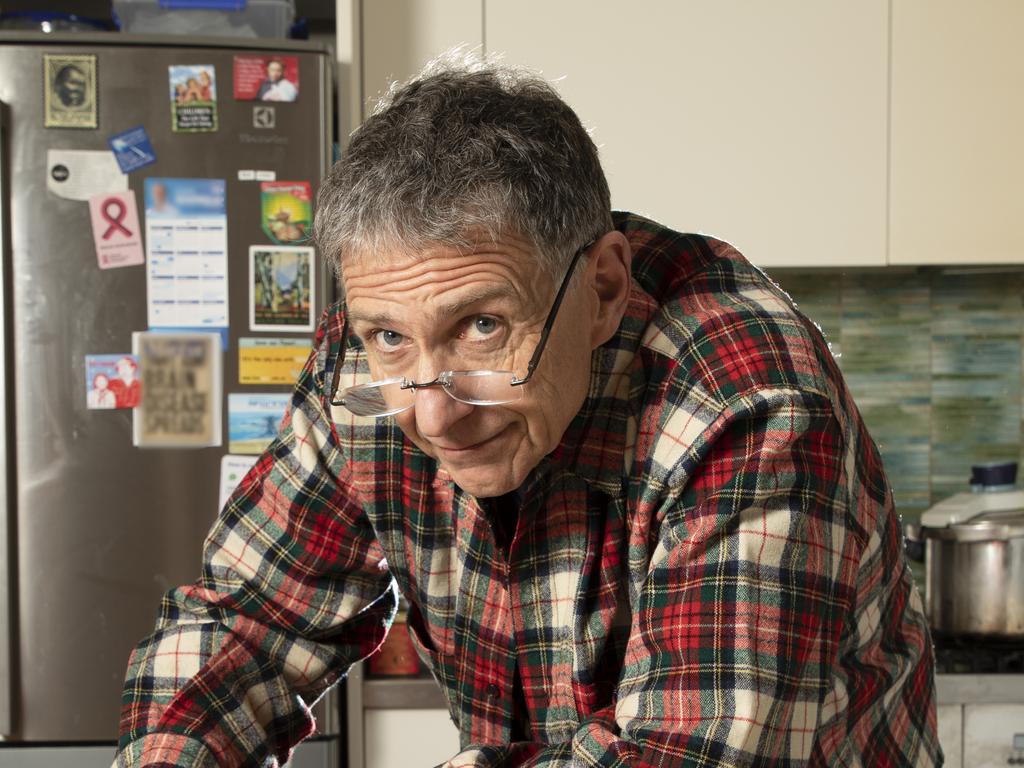

Patience will be rewarded as you try these new recipes from Phaidon’s Persian cookbook, writes Christopher Zinn

I hope that readers will, by now, know this format: I take a recipe book, and cook from it, for family and friends. I then write a review, and you decide whether the book – in this case, Persian Feast – belongs in your collection of cookbooks.

I should say at the outset that Persian food is unlike any other cuisine I’ve risked (I’ve cooked from British, Portuguese, French and even an Australian cookbook for this series of reviews) when planning a feast.

The theatrical presentation and layering of flavours, not to mention specific ingredients, such as dried limes, copious saffron, piles of herbs, dried rose petals, pomegranate seeds, barberries, sour cherries, can be daunting to contemplate.

It takes time, finesse, and a large table to display your banquet with the requisite Persian panache. The tradition includes sitting on the floor surrounded by food.

You may need to “bloom” the expensive saffron in warm water, and yoghurt is needed in high volume, so I fermented litres of it and saved the sour and tangy by-product Iranians call “kashk” for garnishing

It is important to me to invite guests from the nation in question and, thankfully, we found the delightful Fahame, who came here as a student 10 years ago. She could answer most questions about her country and set the scene by reading extracts from the Rubaiyat Of Omar Khayyam in her native Farsi.

Persian Feast is a formidable primer into a 5000-year-old culture, as seen through one of its many gifts to the world: food.

It’s more than a cookbook, although it contains enough salads, soups, stews, and other sundry recipes for rice, fish, potages, drinks, and a few sweets to fill you with mystery and wonder.

The authors remind us that Iranian cuisine, situated at the crossroads of East and West, is among the most sophisticated in the world. The book offers ample evidence. The recipes and tips are tailored for the Western pantry and kitchen, yet the flavours remain 100 per cent Persian.

The book is also an emigre‘s account of Leila Heller’s cosmopolitan family who fled Tehran in 1979 after the overthrow of the Shah.

The location for our Persian feast was our newly rented Queenslander, with an adequately equipped kitchen. Too many of my platters, gadgets and food processors were in transit.

No one was expecting stuffed peacocks, but anticipation was high.

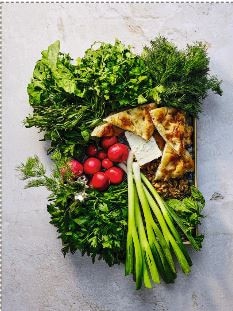

We opened with a sabzi Khordan or the herb platter of basil, mint, coriander, tarragon, spring onions, feta, and soaked walnuts said to accompany every Persian meal. The beloved Iranian lavash flatbread came from a local market.

It was hard to choose from Heller’s many salads. However, all involve fine chopping, none more so than the Brussels sprout salad. The divisive vegetable recalls a faraway city but originated in Iran and Afghanistan. The three cups of dill transformed the raw sprouts into something pretty special.

The eggplant dip did not contain tahini like the average baba ganoush. It was quite a different concoction, with mint, ground walnuts, goat’s cheese, and the kashk from my yoghurt making, and it was all the better for it.

The name alone suggested the pistachio soup or soup-e pasteh had to be on the menu. It called for three cups of shelled nuts, two leeks, chopped herbs, and citrus juice. Garnished with slivered pistachios, rose petals and fresh pomegranate seeds, it proved smooth, subtle and unforgettable.

The mains included mashed lamb and mung beans, and despite the turnips I’m not sure I did this speciality from the Isahan, one of Iran’s most beautiful cities, any justice.

A vegetarian version of the herb and Persian lime stew might have made some amends, mainly for the role played by the dried dark fruit, which needs to be carefully pierced and soaked to liberate its smoky, sour and citrusy flavours.

Heller reminds us that even the staple rice dishes must feature the burned offering of the tahdig, which literally means the bottom of the pot. After the rice is served, the crust remains “infused with saffron and butter, giving it a vibrant colour with the most delicious crunch”.

There is a Persian take on Russian salad and even frittata, plus a recipe for chicken kebabs, with a mouthwatering marinade and buttery basting sauce, which elevated these skewers to paradise, far above the usual hell of fast food.

As with most of our dishes, the kebabs were adorned with lemon, herbs and radishes. The garnishes ran wild with pomegranate seeds, and there’s an unskippable section in the book on the venerated torshi or chutneys and preserves.

There was hardly room in the guest’s bellies for the cardamom and rose water pudding or the light saffron rice pudding infused with rose water and decorated with sprinkled cinnamon.

But being a feast, the surprise appearance of the saffron ice cream, not from any recipe but courtesy of the friendly Persian supermarket, changed all that.

One key difference between this volume and the other Phaidon cookbooks is the small number of sweet dishes such as cakes and biscuits.

As you’d imagine, it is beautifully illustrated and designed, and there’s even an essay on “culinary dabbles in modern Iranian art” to digest as the stews simmer.

My only quibble was the lack of even one ribbon marker in the spine to help identify specific pages. I had so many dishes on the go at the same time I needed at least five colour-coded ribbons to find my place.

Fahame, who has since been home for a visit, just sent us photos of the abundant fruit and herbs from Tehran’s market during their recent (March 20) New Year.

The night before, we had seen The Seed of the Sacred Fig, an Oscar-nominated film that, like its director, is not welcome in Iran. The film featured cooking and eating straight from the recipe book but focused powerfully on Iran’s violent repression and simmering rebellion.

The subtext of regional politics provided a sobering reflection on our feast and, indeed, the book on which it was humbly based.

As the Iranian-US chef and food writer Samin Nosrat says: “Persian cuisine is, above all, about balance – of tastes and flavours, textures and temperatures. In every meal, even on every plate, you’ll find both sweet and sour, soft and crunchy, cooked and raw, hot and cold.”

I may never have started if I’d known that before, but it was worth trying. I have enough leftover sour cherries, saffron, and Persian limes to mount another feast, more than enough recipes, and the experience to do them and Persian cuisine justice.

Christopher Zinn is an enthusiastic home cook. He has previously reviewed Phaidon cookbooks from Australia, France, Portugal, the British Isles, and Indonesia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout