Review of Artifactual Fictions exhibition at Macquarie University

Objects in the Macquarie University History Museum have inspired an artistic response to their depiction of myths and fables.

If the Nicholson, founded in 1860, is the oldest and largest archaeological museum in Australia and, indeed, in the Southern Hemisphere – it is now incorporated within the University of Sydney museums complex in the Chau Chak Wing building – Macquarie University History Museum is one of the youngest, its archaeological collections going back to the mid-1970s.

Nonetheless, attached as it is to several fine academic departments at the university, it has an impressive teaching collection of both ancient and Australian material set out in a handsome new museum building.

The display system is intelligently designed to allow visitors and students to get close to most of the works and see them from both sides in glass cases while making it possible to dispense with security guards and warnings against touching the displays. Strengths in certain areas, such as glass, are immediately apparent, and indeed the museum’s collection of ancient glass turns out to be the most comprehensive in Australia.

Glass is, culturally speaking, an interesting material because it is not as universal as ceramics, which appear wherever civilisation develops. It was first discovered in Mesopotamia in the Bronze Age, and it was only in the first century BC that the technique of glassblowing was invented in Judaea or Syria, followed by clear glass in Alexandria at the end of the first century AD, after which it rapidly came to be produced in vast quantities and widely exported.

Ancient coins are another special focus of the collection, largely thanks to Dr William Gale, with whose support the Australian Centre for Ancient Numismatic Studies was founded in 1999; the subsequent bequest of his and his wife’s collection of ancient coins in 2007, together with funds for further acquisitions and research, greatly enhanced the collection which now contains more than 5000 coins, has a dedicated research library, hosts research fellows and organises seminars on ancient numismatics.

Coins are often beautiful but above all are fascinating historical artefacts, packed with social, cultural and political significance. They were first used by the Lydians – whose king was the proverbially wealthy Croesus – in the early 6th century BC and were then enthusiastically taken up by the Greeks, who understood their use both in trade and also in the promotion of the identity and image of their many independent city states. As historical remains they are also records of successive reigns and regimes. Coins from the turbulent 3rd century AD, for example, are sometimes the only evidence of the brief hold on power of rival emperors.

A small display deals with the unusual form of so-called incuse coins. The usual process for striking a coin involved two negative moulds, the lower one fixed on an anvil, the upper one in a handheld punch. A blank of heated and softened silver was placed on the lower mould, then the punch was placed on top and struck with a hammer. In incuse coins, on the other hand, the mould on the punch seems to have been a positive rather than a negative, so that the reverse of the coin was marked by an inset or concave design. Examples here include a silver stater with the simple motif of a barley ear from Metapontum in the instep of the boot of Italy, famous as the city where the great Pythagoras died.

There is a good sample of ancient vases as well, of which the Greek ones, both earlier black figure and later red figure, are full of mythological subjects, sometimes easy to identify (the death of Actaeon, torn apart by his own hunting dogs) and other times harder to pin down. Ceramics are relatively fragile, but virtually imperishable, and many have been recovered in fragmentary form, often discarded when broken thousands of years ago. The collection accordingly does not present only reassembled and restored vessels, but one in a partial state of reconstruction, while another installation presents a whole group of fragments with tantalising glimpses of narrative subjects, just as they might be found in an archaeological dig.

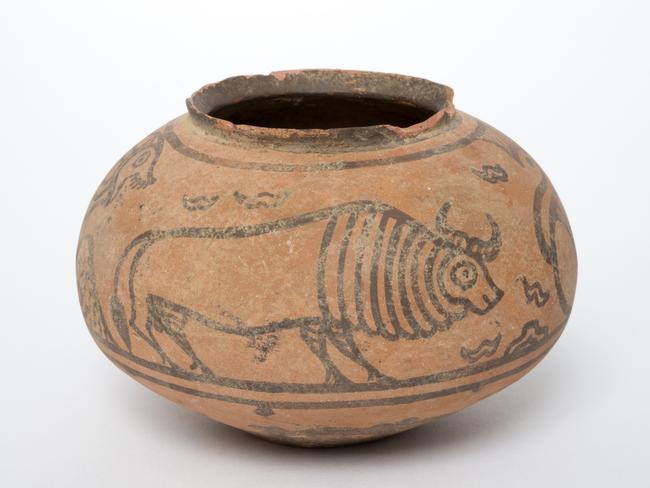

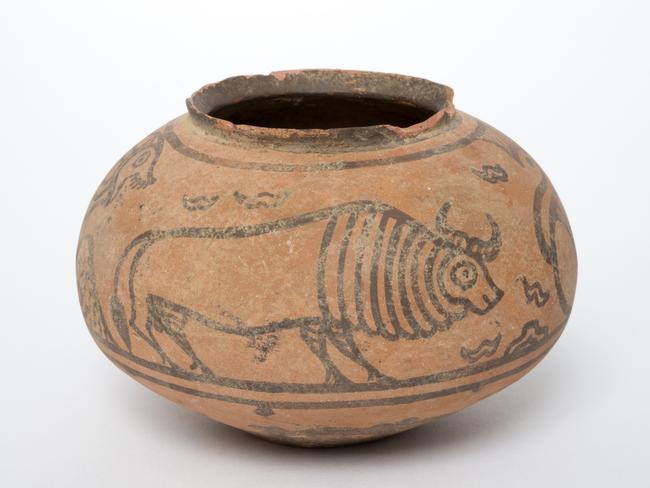

The ceramic collection does not focus only on classical Greece or the Roman centuries. There are wares from at least 3500-4000 years ago, from ancient Egypt, Cyprus and the Near East, and cuneiform tablets – the world’s earliest form of writing – from even earlier. There is a wall of amphoras retrieved from shipwrecks, a fine collection of plain but elegant vessels made by the ancient Hebrew people in Israel from around the time that Moses led them back from Egyptian captivity to the Promised Land in the 13th century BC, and others from the 8th century, the time of Homer in Greece.

There is a particularly beautiful vessel from Baluchistan that may date to around 2500BC. Baluchistan is a region that overlaps with modern Iran in the southeast, and with Pakistan and Afghanistan. It was the location of the first Indus Valley civilisations, and it is interesting to see that the decoration of this vessel consists in a procession of bulls. One of the bulls is being attacked by a lioness, perhaps prefiguring the later pairing of bull and lion on the coins of Croesus, and later still the famous reliefs at Persepolis of the solar lion attacking the earthly bull, signifying the onset of spring.

A friend to whom I mentioned some of these items asked, almost without thinking – such is the contagion of unthought ideas – whether these things should be “returned”. I pointed out that this question was irrelevant in the vast majority of cases. Most archaeological items such as the ones in this museum, while extraordinarily valuable for what they can tell us about the past, are not uniquely precious in themselves. There are hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of ancient ceramics of various kinds and quality. A few are unique treasures, but most are important above all for what they can teach us. And it is right for them to be shared around the world, where more people have access to their study and enjoyment.

We can forget, in today’s climate, how important museums are as places of human knowledge. Even when commentators are not making facile remarks about “stolen” objects, they will often suggest that the comparativist approach of museums embodies some kind of Western perspective that is forcibly imposed on other cultures. This is only true in the same sense that science in general claims a status of objectivity superior to tribal myth and magic (including to the myth and magic of Western traditions).

Museums give us the opportunity to see the world’s cultures side-by-side and within a historical framework that is inherently free of any parochial or tribal self-centredness, and that enriches even the perspectives of individual and particular cultures.

This historical and archaeological museum has inspired a joint exhibition by two artists, Hadyn Wilson and Patrick Shirvington, which is located not in the museum itself but in the foyer of the university library, next to another remarkable item in the university collection, the sitting room of Governor Macquarie’s house in Scotland, whose furnishings were completed after his death by his widow.

The two artists have collaborated in producing this exhibition, but their sensibilities are very different: Shirvington is more poetic and whimsical, Wilson more documentary and political, and yet what they have in common is their imaginative transformation of the material that they have borrowed or taken as their starting point.

Thus Shirvington has drawn primarily on the archaeological material in the museum, intrigued by glimpses of ancient Sumerian or Egyptian belief and magical practices. There are samples of papyrus that he has reproduced, and drawings inspired by the countless enigmatic objects found in archaeological digs. One ink drawing reproduces a satirical image from ancient Egypt showing a feline attendant waiting on its master who is a mouse. Shirvington’s facility for witty and charming drawings brings many such vignettes to life.

The most consistent series of his drawings is devoted to the ancient storyteller Aesop, whose original Greek tales survive in various later Greek and Latin retellings. In one case the story of the Hares and the Frogs – where the hares think themselves the unhappiest of creatures until they realise the frogs are scared of them – is written out in Greek and also in English translation.

Several other drawings illustrate stories from Aesop, both famous, such as the Hare and the Tortoise, and less familiar, the Fox and the Mask. A related ink drawing illustrates the injunction of the Delphic oracle – “Know thyself” – and contrasts the figure of a man tottering in the dark with several Aesopian animals who seem comfortable in their environment and watch him in bemusement.

Wilson is inspired by more recent material, mostly from fragments of Australian social history from the later 19th or 20th centuries. He typically combines collage or assemblage of images and artefacts, and often juxtaposes these with documents such as letters or pages from books and other publications. Sometimes these evoke social and political themes such as the suffragette movement, at other times they are more elusive yet more memorable.

One such set includes a found photograph of a little girl, from the late 19th century, together with an open book, perhaps just 50 years old but yellowed from the acidity of the cheap woodpulp paper, whose text is separately transcribed for easier reading. In it, a man tells of discovering a photograph of his great-great-grandmother as a little girl and of realising with a shock that her features were identical to those of his own daughter. To add to the strange resonance of this text and image, Wilson has commissioned a friend to produce an AI-generated frontal portrait of the little girl, who is seen looking up and away in the original.

But Wilson has done something else, which is perhaps the most interesting of all the interventions that he makes in these intriguing combinations of assemblage and dislocation: he has made a handpainted copy, in black and white, of the photo of the little girl. There are many other examples of this process in the exhibition, including the repainting of a photo of a little girl dressed as a nurse, and of a group of young people in 1930 in Washington State, accompanied by a touching letter from a young man to a girl whose family are about to – and in the event no doubt did – move to Sydney.

Repainting an inconsequential snap, found almost at random among myriad others in a historical archive, may seem an odd thing to do. Yet, like the retelling of an old story, this new act of picturing breathes fresh life into the desiccated image, as though in a process of “artifactual” metamorphosis in which the element of fiction paradoxically brings a new quality of imagined reality to the factual yet forgotten.

Macquarie University History Museum

Hadyn Wilson and Patrick Shirvington: Artifactual Fictions – Unseen Dialogue

Macquarie University Library, until March 31

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout