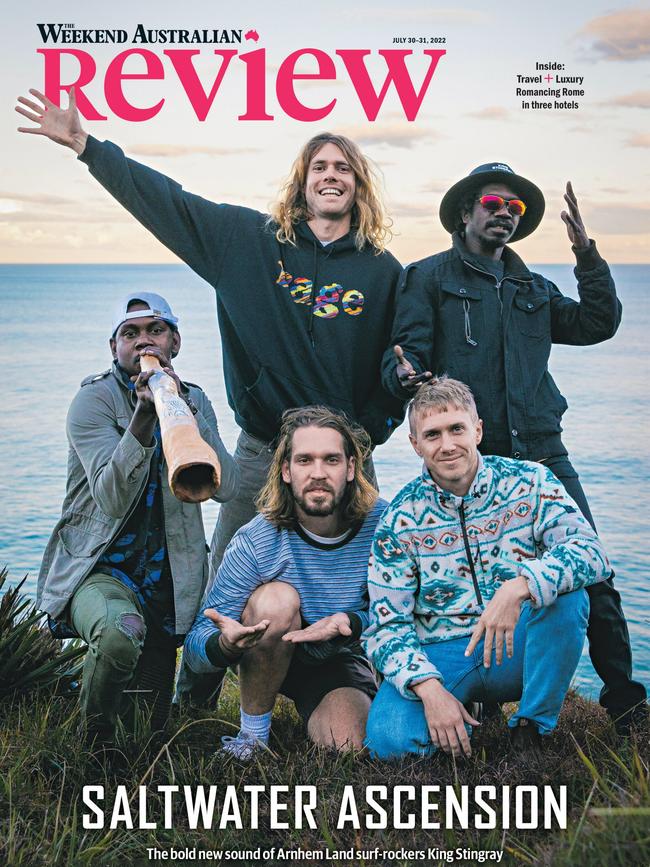

How a little-known Arnhem Land act took Yolngu surf rock to the world

Four years ago, before King Stingray’s live debut, none of them knew where this music might take them; the prospect of playing at venues filled with up to 15,000 Americans would have felt like a pipe dream. But now they’re here.

Of all the human emotions, there’s one feeling that might be the trickiest to pin down.

Derived from the Greek words for “home” and “pain”, nostalgia is a heavy lift to summarise in words, let alone any attempt to pair it with rhythm and melody, while searching for greater meaning in song.

The degree of difficulty becomes higher when you consider nostalgia means different things to each individual.

A favourite track that links deeply to your path of life experience might leave your neighbour cold and unmoved; you’ve connected that song to a time and place that means the world to you, but little to them.

The span from adolescence into adulthood often forms the most potent cocktail of musical nostalgia. Sometimes we love songs simply because they remind us of our younger selves, whose time seemed limitless, and whose potential sat atop a skyward ladder.

Once the feeling is captured, some performers spend a lifetime seeking to re-bottle and resell that heady brew. “I think nostalgia can be a real trap for an artist,” wrote Elton John in his 2019 memoir. “When you reminisce about the good old days, you naturally see it all through rose-tinted spectacles. In my case in particular, I think that’s forgivable, because I probably was literally wearing rose-tinted spectacles at the time … But if you end up convincing yourself that everything in the past was better than it is now, you might as well give up writing music and retire.”

It’s one thing to acknowledge nostalgia, and another matter entirely to write music around this theme at any stage of one’s career.

Yet with only a couple of dozen songs to its name, NT rock band King Stingray has not only attempted this risky brief, but nailed it.

Midway through the tracklist on its second album – the optimistically named For the Dreams – the six-piece band plants its flag in the ground with a song whose title doesn’t shy away from the task at hand. It’s called Nostalgic, and amid a chiming acoustic guitar riff, a bustling drumbeat and gentle keyboard notes, its second verse begins:

Do you remember the song that was playing?

What was the name of the place that we were staying at?

Was it out west where the wind took your breath away?

Living in a world of constant change, look what we made

Some memories fade, but this one’s gonna stay…

It’s a highwire act to write so directly about such a complicated emotion, yet with Nostalgic, the band’s core songwriting duo of Yirrnga Yunupingu and Roy Kellaway has captured something that’s almost ineffable.

The decision to incorporate conversational dialogue into the lyrics is a strong one, too, that calls to mind a couple of Australian country/folk standards – True Blue by John Williamson (1986) and Not Pretty Enough by Kasey Chambers (2001) – whose choruses both contain a series of questions posed to the listener.

In the chorus of Nostalgic, several of the band members’ voices blend together in harmony as they sing:

Recently I’ve been feeling a little bit nostalgic

It keeps on happening and I don’t really mind it

We’re talking all night and we’re staying up late again

It’s the dreams we have and the memories we make.

This four-minute song is so expertly executed, and so moving, that it demands answers as to its origins. Where did it come from?

“We were in Austin (last year) at this awesome Airbnb, out on the deck ’til the late AM, talking shit and reminiscing on different things in life: when you’re a kid, or what happened a couple of weeks ago,” guitarist and songwriter Kellaway, 28, tells Review.

“We like to reminisce: we talk about all the good times we’ve had, and at the same time, we’re making new memories; that little bit of irony was an interesting concept.”

“When your lifestyle changes, and you become a professional touring artist, it’s nice to just have a breather, gather your thoughts and go, ‘Remember this?’ We’d just done lots of shows, and we were feeling really jet-lagged and nostalgic; really grateful and appreciative.”

Says drummer Lewis Stiles, 30: “We do hang out in hotel rooms quite a lot. But when we were overseas in Austin, we got this mad house, and we had all this free time to hang out together. It’s f..king amazing, you know, to just sit around and shoot the shit; swim together in the backyard pool, watch TV, fall asleep with your hand in a chip packet… Oh, we’re doing it now! Nostalgic!” His bandmates laugh.

“Friendship’s a big part of our life; mateship, relationships and friendships,” continues Kellaway. “I think maybe at first glance, we’re singing about our story – but these stories are real innate human feelings, too, and that’s what we want to try and bring to the surface. Nostalgia is quite a relatable concept that all humans probably feel at some point in their life; that concept of some memories staying with you.”

Stiles nods, and says, “I think also, because touring life is so fast-paced – get into the cab, go to the hotel, go to the gig, to the airport, next gig – whereas up in Arnhem Land, you do actually just stop and spend time. We also really like playing music, and you do have to actually do the hotel rooms, the airport and everything else to be able to do music.”

At this, Kellaway – who specialised in Indigenous podiatry before this band’s music took over his life – replies: “They teach you this in healthcare, too: you can’t begin to understand someone’s story without sharing your story. It’s a two-way street, learning about each other and talking stories; it’s a shared thing”.

He pauses, then says with a wide smile: “I mean, we’ve gotten to know each other pretty well over the last few years”.

It’s an odd thing for a relatively young band to be writing about the complex emotion of nostalgia, given the group is composed of men in their late 20s who are only four years and two albums into their shared existence.

But considering the speed at which King Stingray has transformed from a little-known Arnhem Land rock act to an acclaimed and in-demand live draw, that inspired songwriting decision to briefly look back – Living in a world of constant change, look what we made – makes perfect sense.

When Review last profiled the band for a cover story, it was mid-2022, and in the lobby of a Brisbane hotel where the group’s manager was ably handling a cresting wave of national interest that had resulted in bookings quickly filling up for the remainder of a busy year of activity, which had also included the release of its self-titled debut album.

The thumbnail sketch of King Stingray’s story so far is this: three of the band members grew up on the same street in the NT community of Yirrkala, about 1000km east of Darwin.

The trio’s lineage is directly linked to two rock groups with deep roots in Indigenous Australia: singer-songwriter Yirrnga Yunupingu’s uncle was Yothu Yindi frontman Mandawuy Yunupingu; Kellaway’s dad, Stuart, is the founding bassist of Yothu Yindi, and guitarist/singer Dimathaya Burarrwanga’s grandfather was George Burarrwanga, the charismatic singer and didgeridoo player in trailblazing rock act Warumpi Band.

Together they sought to establish a cross-cultural sound self-described as Yolngu surf-rock – so named for the inhabitants of northeast Arnhem Land – which was solidified once Kellaway linked in with drummer Lewis Stiles and bassist Campbell Messer in Brisbane.

Since the band’s ARIA Award-winning self-titled album release – named best album of 2022 by Review, while its single Get Me Out was recently ranked in our list of the 60 best Australian songs of the past 60 years – it has added a sixth member in Yimila Gurruwiwi, who plays didgeridoo and sings backing vocals.

King Stingray’s live performance career, meanwhile, surpassed 100 concerts in April last year with a high-profile gig at the Formula 1 Grand Prix in Melbourne, having debuted in December 2020 while supporting Sunshine Coast punk rockers The Chats in southeast Queensland.

At once scrappy and polished, raw and powerful, these musicians have developed a reputation for playing loud and proud while standing alongside one another, as Yolngu and balanda (non-Indigenous) men, sharing songs and stories – sung in both English and Yolngu Matha – that today attract 173,000 monthly listeners on Spotify alone.

When Review reconnects with King Stingray in mid-October at a Sydney rehearsal space, where they’ve been preparing for a recording session at Triple J’s popular Like a Version cover song series, there’s a few personnel changes afoot: Yunupingu is on country for personal reasons and Messer is out injured, so Mark Chester Harding has been drafted as a temporary bass replacement, and Jem Cassar-Daley (daughter of country musician Troy) has joined on keys and backing vocals.

The mood is relaxed and jocular – there’s that unifying sense of mutually respectful mateship mentioned earlier – but as they agree to play a single from the upcoming second album, things quickly turn serious once Kellaway begins picking the opening guitar phrase. Yaka muckaround, as they say in Yolngu: we’re not mucking around.

The first song they run through is the album closer, Cat 5 (Cyclone), a highly melodic rock arrangement that follows a new songwriting path wherein, rather than alternating languages, all choruses are now sung in English, resulting in rich harmonies as five voices blend together.

Observed from a short distance at high volume in a small room – with Burarrwanga and Gurruwiwi singing toward a bare wall, with their backs to Stiles, to mimic their stage positioning in concert – the connection between the musicians is readily apparent. It’s all the more impressive given that the band rarely rehearses together, as home for the core six members extends from Arnhem Land down to various east coast cities.

As it ends with a gorgeous vocal coda and the striking image of looking into someone’s eyes and seeing blue skies, Kellaway kicks off his shoes, turns to his colleagues and says, “All right, we may as well try the cover, hey?”

His bandmates give assent – “Let’s go!” shouts Burarrwanga – and the guitarist tells Review with a smile, “This one we’ve pretty much just made up today. It’s good that you’ve come, to force us to do it again, because we probably need to”.

We’re sworn to secrecy on the choice of song, as it’s planned to debut on the radio and online this month as part of Triple J’s annual Ausmusic Month. What we can say is the cover is a surprising one, wherein the group applies a new flavour to make it unmistakably their own – similar to its last Like a Version in 2022, when it added Yolngu Matha to Yellow by British rock band Coldplay, resulting in a memorable new take on a familiar song.

When Gurruwiwi blows his didgeridoo – nicknamed ‘Legend’ – into the microphone at full force, the walls of this small space reverberate with the bass drone, and goosebumps flash across our skin at the unearthly sound and sensation. Not since its musical forebears Yothu Yindi has a popular Australian act so successfully, and essentially, incorporated this traditional Indigenous instrument into its arrangements.

Later, over dinner and drinks at a pub in Glebe, Review asks what the inclusion of sixth member Gurruwiwi has meant to the group. The didge-wielding man himself is shy to the point of silence – English is far from his first language, and he’s uncomfortable speaking it to a stranger – but de facto spokesman Kellaway is happy to respond.

“In a way, he’s kind of always been in the band from the beginning; in our first ever press shots, he was there,” says the guitarist, smiling at his bandmate. “His presence is a lot more on this new album, with the yidaki (didgeridoo) playing. It’s a big part of who we are. I feel like I can’t imagine doing a gig without him. We did do a few in the very beginning, because we didn’t have enough money, and it’s so expensive to get everyone out of Arnhem Land. But we go way back, from when we were kids.”

Recorded in fits and starts on and off the road, amid touring commitments, the band’s self-produced second album sidesteps a common trap for successful debuts: rather than becoming inwardly focused in subject matter, primary writers Kellaway and Yunupingu wisely keep the lens on topics much larger than themselves, from nostalgia and nature to a love of friends and community.

Naming the album For The Dreams, too, prompts an obvious question: what do these energetic, inspiring and talented young men hope for their future?

“All my dreams have come true: I’ve got a beautiful family, a beautiful partner, beautiful friends,” says drummer Stiles, the eldest member of the band. “I’ve got all these amazing things; I’ve done so much with my life, and I’m so proud of that. If I had to dream of anything else, I don’t know; this album is for the dreamers, because we wrote it while we were on the road, living out our dream,” he says with a laugh.

As for Kellaway? “I’m just overflowing with dreams,” he replies. “I would love to see a world where humans can work together and live a bit more harmoniously, multiculturally, and just be a bit more understanding of people. Music brings people together, and that is important to me; everyone deserves music.”

Guitarist/singer Burarrwanga is a man of few words in interviews, but when he speaks, it’s often with a wisdom well beyond his 29 years. When Review puts this question to the group, he doesn’t hesitate to offer up this response while thinking of Yirrkala, a place never far from his mind.

“My dream: I’m gonna build a youth centre back home for kids to learn music, to maybe give them opportunities for their generation to come and share their music with their people,” says Burarrwanga, drawing nods and approving cheers of “Yo!” from his bandmates.

At this, we raise our glasses and toast the album title. What lies ahead is the release of a swag of new songs followed by playing to some of the biggest crowds they’ve ever faced, thanks to a run of US dates supporting fellow Australian rock act King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard.

Yaka muckaround. There’ll be no mucking around with opportunities of that scale, and while Yunupingu and Gurruwiwi will stay on country, for Burarrwanga this four-week trip will be one of the longest stints he’s ever spent away from Arnhem Land.

Four years ago, before the band’s live debut, none of them knew where this music might take them; the prospect of playing at venues filled with up to 15,000 Americans, as they’ve begun doing in early November, would have felt like a pipe dream.

But now that they’re here, on the cusp of ascending yet more rungs on a skyward ladder, they’ll try to remember to take a breather, look at what they made, and remind each other: some memories fade, but this one’s gonna stay.

For The Dreams will be released on Friday, November 8 via Civilians. King Stingray’s five-date album tour begins in Sydney (March 21) and ends in Fremantle (April 4). The writer travelled to Sydney as a guest of Civilians.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout