Loud and proud: the remarkable ascent of ‘Yolngu surf-rock’ band King Stingray

Inside the bold new sound of this self-described ‘Yolngu surf-rock’ band from Arnhem Land, which has blood ties to two iconic Indigenous Australian bands.

Home for the rock band King Stingray is the small community of Yirrkala in northeast Arnhem Land, a part of the country that is wild, raw and alive. Set near the far tip of the Northern Territory about 1000km east of Darwin, it’s a place that feels to them like paradise.

Growing up there, kids tend to split their time between the local school and Shady Beach – a haven for fishing where Miles Island is within paddling distance of the shore – as well as the local football oval and the Buku-Larrnggay Mulka, which is one of Australia’s premier Aboriginal art centres.

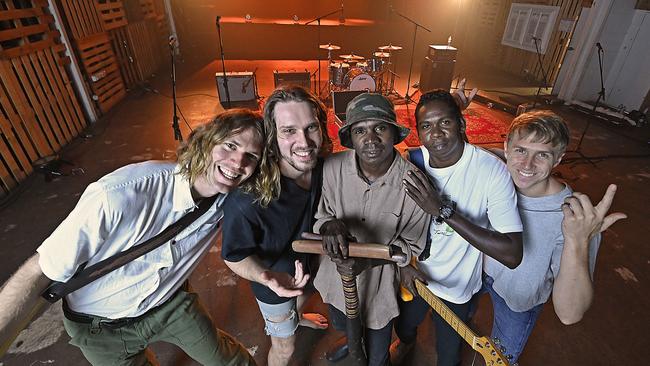

Yirrkala is where three-fifths of King Stingray were raised: singer Yirrnga Yunupingu – whose name translates into English as “place of stingray” – and guitarists Dimathaya Burarrwanga and Roy Kellaway all lived on the same street.

Besides a love for surfing, fishing, footy and all things outdoors, the trio shared a deep passion for music, one that saw them playing guitars, drums and singing together from a young age. Some children will do anything to resist following a career path carved by their forebears. Given the influence and cultural power of their respective lineages, the less risky option for these three young men would have been to pursue something other than music.

Dimathaya’s grandfather was George Burarrwanga, the charismatic singer and didgeridoo player in trailblazing rock act Warumpi Band, while Yirrnga’s uncle was Mandawuy Yunupingu, the frontman of Yothu Yindi – the globetrotting group in which Roy’s father Stuart Kellaway was founding bassist.

They are the twin pillars who have inspired generations of Indigenous Australian musicians since their bands were formed in 1980 and 1985, respectively. Their legacy as songwriters and performers looms large across all who have followed them across the decades.

Thankfully, though, the three childhood friends did not resist the titanic tug of history. Instead, they have been navigating an artistic path of their own, one they call “Yolngu surf-rock” – so named for the inhabitants of northeast Arnhem Land – which has seen King Stingray make a mighty big impact in a short space of time.

Their home was immortalised in the imagery of the band’s breakout song, Get Me Out. Built on a laid-back drumbeat, a busy bassline and melancholic guitar chords, it tells a story of yearning for Yirrkala – “a place where you live and a place where you grow” – while feeling trapped in an urban environment.

“This is your lifestyle / You can be who you want to be / You can do what you want to do,” sings Yirrnga Yunupingu as the song’s gentle, spacious arrangement opens up after the first verse. “Feel the cool breeze on your face again / Feel the rain on your heart / Running back to you...”

Then Yunupingu’s bandmates kick into high gear, with electric guitars alternately peeling off a spindly, chiming lead break and chopping through an emotive chord progression as the rhythm section ups its pace.

“The colours are changing djapana (sunset) / I know my home is never far away / Get me out of the city,” the three Yirrkala boys sing as one. Their vocal harmonies blend masterfully, before Yunupingu’s stunning voice scales new heights in his native language. This is a sound at once new and old; a meeting of modern songwriting smarts with Yolngu Matha vocalisations that were developed and passed between generations of Arnhem Land’s original inhabitants long before the first balanda (non-Indigenous person) strapped on an electric guitar and plugged it into an amplifier.

Released in January 2021, as the eastern states were once again undergoing Covid lockdowns that shrank the horizons for millions of Australians, it was apt that this track and its escapist imagery soon became a playlist staple on national youth broadcaster Triple J; it ultimately placed No.46 in the radio station’s Hottest 100 music poll earlier this year.

Get Me Out was the second song the band had issued, a few months after the arrival of its debut single Hey Wanhaka in October 2020. Both songs showcased an expansive, engaging rock ’n’ roll style that immediately jumped out of the speakers as a result of its potent, artful combination of words and music.

It sounded unlike anything else in mainstream Australian culture, and it hinted at a big future for King Stingray, a quintet completed by drummer Lewis Stiles and bassist Campbell Messer – two musicians with whom Kellaway was linked when he moved to Brisbane to work in Indigenous health care.

Just as the group mixes Yolngu and balanda musicians, its name was chosen for its contrast and juxtaposition signifying multiculturalism. The king and the stingray: a man-made royal leader and a sea creature that appears to glide effortlessly and majestically in its habitat.

The pandemic set back the group’s touring plans, and it didn’t help that flights into and out of Arnhem Land via regional airline Airnorth were already unpredictable at the best of times. Its first public performances were in December 2020, supporting Sunshine Coast punk-rock band The Chats at several shows in southeast Queensland, followed by a gig at Nhulunbuy Town Hall, about 20km from Yirrkala.

By the time King Stingray arrived at Brisbane’s Valley Fiesta in October last year to play the biggest headline show of its career at The Tivoli theatre, the quintet had less than 20 concerts under its collective belt. Yet that night, the young men put their songs across with an uncommon confidence that belied their nascency, and the buzz in the full room of about 850 people was contagious, as electricity crackled from a full dance floor of fans to the musicians and back again.

The players themselves – particularly the rock-solid rhythm section of Stiles and Messer – displayed an unusual and charming trait of celebrating their performances between songs, as plenty of high fives, fist bumps, handshakes and grins were exchanged between all five members. It was wonderful to see their mutual respect and admiration for one another, as it exemplified a sense of pure joy in shared musical expression that is rarely witnessed.

As well as the strong suspicion that we were watching one of Australia’s greatest young bands in action, Review was struck by the feeling of seeing a bunch of good mates simply having a blast at nailing these powerful, propulsive rock songs before a receptive audience.

With just three songs released at that time – Hey Wanhaka, Get Me Out and the irresistibly upbeat party track Milkumana, which pivots on a fleet-fingered bassline and an intricate drum pattern – much of the music heard that night was unfamiliar, apart from a cover of the storming Warumpi Band song Waru (Fire). Yet thanks to Yunupingu’s stage presence and his incredibly powerful, emotive voice floating in the centre of the mix, it was easily one of the strongest concerts I saw all year.

Speaking with Review two days after that Brisbane gig, guitarist and back-up vocalist Kellaway is still basking in the afterglow, and truly touched by the memory of seeing and hearing that crowd response.

The last time he and Yunupingu performed at The Tivoli was with Yothu Yindi and the Treaty Project three years prior; that they were able to fill that same room while singing their own songs just a few years later has his head spinning.

“We genuinely are having the time of our lives when we play together, and nothing makes me happier to rock it out with my mates in this band,” he says. “It’s literally the funnest shit ever, and there’s so much love.

“I’ve never done anything where we’re hugging before the gig, during the gig and after the gig; so much hugging and high fives,” says the guitarist and songwriter, his grin detectable even over the phone. “Yothu Yindi were a lot like that: so much love, because it’s a family concept. The idea of celebrating culture comes with (the idea that) you’ve got to practise what you preach. We do treat each other like a family, as well as sing about it.”

As Kellaway explains, King Stingray had been in the works for several years. Inspired by their time on the road with the Treaty Project in 2018, he and Yunupingu – who he describes as his wawa (brother) – were dreaming of starting a new outfit.

“We got a bit of a taste for it on the road, and we were thinking about how we can do our own thing and follow in the footsteps of some legendary family members of ours,” Kellaway says. “It really began from me believing in my wawa Yirrnga, and helping him try and get his music out there, where it deserves to be – he’s such an amazing artist. I knew we wanted to do this Yolngu surf-rock, so I pulled together the band, and it just clicked straight away.

“It’s definitely happened really quickly, which is so awesome, but I’m still currently working as a podiatrist and a diabetes educator with Aboriginal Health Queensland, which I absolutely love, too,” he says. “So I’ve had the plate pretty full, trying to balance it all, because this is my hobby; this is my fun stuff. It’s quickly become a livelihood, in a very wholesome way.”

As well as playing in Yothu Yindi, Kellaway’s father Stuart was the music teacher at the local school in Yirrkala. One of the lessons he imparted continues to echo today, as King Stingray has moved from small-town anonymity to national attention less than two years after releasing its first music.

“He’s always been a mentor for us, and the facilitator of all the good times,” Kellaway says of his dad. “He’s always been around with us and our music. I remember when we were really young and a bit nervous for our gigs, he would come in and give us a bit of a pep talk, like a footy coach or something. He would tell us, ‘Loud and proud; wrong and strong. It doesn’t matter if it’s wrong – just be strong with it, and own it.’

“I think that really resonates with us, and a lot of the musos I love and look up to, like David Byrne from Talking Heads,” he says.

“There’s one part in (1977 single) Psycho Killer where his voice cracks big time (in the ascending chorus melody); it’s the wrong part, but it’s great. I love how he left that in, and I really like the idea of being proud and not taking yourself too seriously.”

When Review reconnects with King Stingray in early June, the band is hours away from the start of a tour in support of Brisbane indie rock act Ball Park Music, which has enlisted the Arnhem Land quintet to play seven dates in large theatres.

In what has quickly become a series of cresting peaks, the goosebump-inducing highs of that Tivoli gig late last year have since been superseded by more recent career highlights.

In late April, the group supported Sydney rock act Midnight Oil on its final national tour by performing before about 12,500 people at Qudos Bank Arena. This was briefly the biggest venue that King Stingray had played in – until a month later, when it performed in the centre of the Melbourne Cricket Ground for the AFL’s Indigenous Round match between Richmond and Essendon.

All of this live activity is leading up to the release of King Stingray’s self-titled debut album in early August. It will contain the five songs released to date, including recent singles Camp Dog and Let’s Go, the latter of which celebrates the road that leads north to Yirrkala: “Central Arnhem highway on my mind / When I think of you I leave my troubles far behind,” sings Yunupingu in its chorus.

It also includes songs known only to the thousands of people who have caught the band’s live shows, including album opener Lupa and eighth track Malk Mirri Wayin, an astounding arrangement built on heavily distorted guitars which rises to an extraordinary call-and-response crescendo that showcases the musicians at full stretch.

Closing song Life Goes On, meanwhile, is both a pleasant surprise and a change of pace, as strummed acoustic guitars lay a gentle bed for some of their finest vocal harmonies.

In the foyer of a hotel at the edge of Brisbane’s Fortitude Valley, Stuart Kellaway is cheerfully juggling phone calls, emails from promoters, touring spreadsheets and media appointments. As King Stingray’s manager – a role he took up somewhat reluctantly, after his son grew tired of balancing the administrative and creative workloads – Kellaway Sr’s most commonly used word this year might well be “no”, as he has been declining just about everything on offer of late.

It’s only halfway through the year but the band’s dance card is full for the remainder of 2022, and he knows his young charges well enough to ensure that breaks are built into their schedule, particularly so that the two Yolngu men can return to the Top End, reconnect with their people and recharge their batteries away from the increasing clamour that surrounds this hot act.

Before they head to the nearby Fortitude Music Hall for a soundcheck ahead of that evening’s show, three-fifths of the group sit down in a quiet corner of the hotel foyer for a quick chat. Roy Kellaway – a tall, long-haired, beatific presence – does most of the talking, with occasional interjections from his two childhood friends; Yunupingu sits and listens, his eyes hidden behind red wraparound sunglasses.

Recorded between Stuart Kellaway’s fittingly named Fifty Riffs home studio in the NSW far north coast town of Tintenbar, and two studios in the Brisbane region – Airlock and The Plutonium – King Stingray’s 10-song debut album is most impressive in how well it captures the strength and sound of the band’s live performances.

When I ask about the message behind the acoustic album closer, Dimathaya Burarrwanga – who plays guitar and didgeridoo and sings back-up vocals – says quietly, “We’re always talking about our childhoods and life – not just for us, but for non-Indigenous people and Indigenous people. We always talk about life, lifestyles and what your aim is for the future, and what you’re going to become. Maybe a rock star, or a businessman; something to earn in your lifetime.”

Asked about the hometown response to the band’s success, Burarrwanga offers a humble statement – “Yeah, a couple of people play us …” – before Kellaway cuts him off with a laugh.

“More than a couple – everyone!” he says. “Just a couple of days ago, we walked into the Hog Shed, which is a little shed that we used to jam at, and the love! You walk in feeling like rock stars.

“There’s people wearing (King Stingray) shirts, and they’re the people that have been supporting us in all of our music endeavours since the beginning, in other bands and as little fellas playing different stuff. They’ve been believing in us, and letting us follow our dream.”

It’s not hard to imagine the sharp uptick in national interest going straight to the head of any ambitious young musician, but these three men each know that no matter how far their music takes them, their roots remain in Yirrkala, the community whose heart beats through the imagery in plenty of these songs.

“Talking about the album tour and things in the future, it’s really easy to just get distracted. You’ve just got to re-centre, and that’s why I love hanging out with you boys, because Yolngu are just so in-the-moment and present,” says Kellaway, gesturing at his friends.

“But there’s a love of music that I see in everyone in the band, and I particularly see it when we do gigs and go out on tour,” he continues. “Yirrnga always wants to jam and muck around, and sing manikay (songs). That’s just a testament to him, and him practising his culture as well, in the city, wherever we are.

“We can be cross-country and far away from home, but the manikay is always there with him.”

A few hours later, the band takes to the stage and catches another couple of thousand people in its proverbial net through sheer charm, power and songwriting quality. By the end of the set, the energy in the room is phenomenal, and it feels as though everyone within earshot is on King Stingray’s side: loud and proud, right and strong.

King Stingray is released on Friday, August 5 via Cooking Vinyl Australia. The band’s album tour begins in Brisbane on October 2 and ends in Darwin on October 22.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout