Isaac Walter Jenner is a little known but rare talent

Painter Isaac Walter Jenner’s personal maritime history and self-taught approach make him a 19th-century artist of distinction, as an exhibition at the Queensland Art Gallery shows.

Isaac Walter Jenner: A Feeling for Light

Queensland Art Gallery, until January 28

Isaac Walter Jenner (1837-1902) was, as this exhibition makes clear, an extremely talented painter and indeed, when we consider that he was essentially self-taught, even something of a prodigy.

He also played an important part in the artistic life of the still very young city of Brisbane and contributed to the foundation of the Queensland Art Gallery. And yet he is surprisingly little known within the broader perspective of Australian art history, and perhaps not much more familiar even to most educated Queenslanders.

The comparison with Jon Molvig (1923-70), whose work was also presented in a retrospective at the Queensland Art Gallery in 2019-20 (reviewed here in October 2019), is particularly instructive. It epitomises the contrast between the kind of artist who is talented and appealing but not considered historically significant, and the kind who is much less technically competent, but who is somehow deemed “important”.

This is a problem typical of the modernist period and inconceivable in past eras. Its roots lie in the new conception of history that arises in the later 18th and 19th centuries. The Enlightenment had already developed its own sense of history as the story of progressive scientific and social improvement in the life of humanity, of rationality gradually dispelling darkness, ignorance, injustice and superstition.

Romanticism, however, invented the modern idea of culture in the anthropological sense of the ensemble of values, beliefs and practices that define the mental and spiritual life of a people. This emphasis on particular cultures was antithetical to the universal values of the Enlightenment, and yet it also influenced a new sense of history as the story of the emergence and formation of peoples and nations; combined with elements of Enlightenment political thought, such ideas led to the nationalism that had such a dramatic and often disastrous effect on history from the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries.

In either perspective, history was turned from a study of the past whose purpose was to help us understand the present and to learn lessons about the art of statesmanship, into a dynamic, radical and volatile force in modern societies. Most importantly, it meant that individuals, movements and particular works came to be valued according to whether or not they were judged to have made a positive contribution to some historical current or other. Even last year in Australia, we repeatedly heard the slogan “being on the right side of history”, when it is in fact only the outcome that shows which side history was really on.

Art has never been about “progress”: the development of perspective did not make “better” painting even if it was a dynamic factor in the history of modern art, nor did its questioning or rejection by later artists such as Picasso or Matisse; the same can be said of sfumato, chiaroscuro, or caravaggesque naturalism. Yet modernism committed itself to a myth of progress and artists were considered “important” on the grounds that they had contributed to a progressivist narrative like the “path to abstraction” or the movement towards flatness. From this point of view painters who persisted with or returned to figuration were ignored, until in the later 20th century the official narrative ran out of steam and in British art, for example, Lucian Freud and David Hockney suddenly seemed more important than any formerly admired abstract painter.

Looking at Molvig’s painting today, there are certainly elements of ability, but a great deal that is simply inarticulate. Above all it conveys no sense that he is making any effort to paint better – why should he when painting badly was almost a mark of being “progressive”? Molvig clearly benefited in his lifetime from a tailwind of fashion; but it was a mixed blessing because it did not encourage him to improve and left his work, after it dropped away, looking like little more than a tired product of its time.

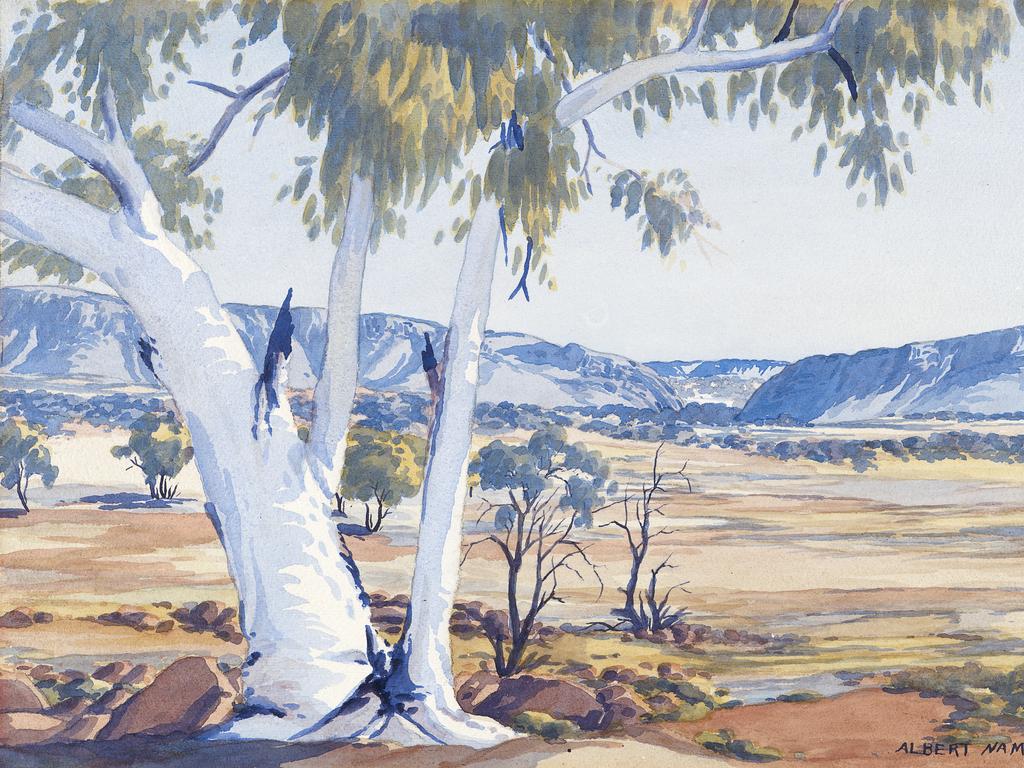

Jenner belonged to a world and an artistic milieu that could hardly be more different. He went to sea as a young teenager with no apparent formal education, and by the age of 18 joined the Royal Navy, in time to take part in engagements in the Crimean War and as far away as Japan. He left the navy 11 years later, in 1865, and at the age of 27 settled in Brighton and somehow established himself as a professional artist. He had been a ship’s painter in the navy, but this hardly explains how he acquired such fluency in the difficult art of oil painting; he had undoubtedly studied early Dutch landscape as well as the work of Turner and other romantic artists. He achieved a certain success in England, but migrated to Brisbane with his wife and seven children in 1883, at the age of 47.

More can be learnt about Jenner and his career from the handsome publication that accompanies this exhibition, and also from some outstanding video clips on the gallery’s website, which explain the artist’s use of underdrawings, provide more detailed information about a couple of works and follow the remarkable process of conserving two paintings that were gifted to the gallery in very poor condition.

Considering Jenner’s profound experience of ships and seafaring, it is not surprising that he became above all a marine painter. But unlike so many works in this genre, Jenner’s marine pictures were neither portraits of famous ships nor accounts of celebrated sea battles.

One of his most impressive images is the vivid and terrifying picture of HMS Retribution at Balaclava: painted in 1895 and in Australia, it recalls a wild storm in 1854 during the Crimean War when many ships were lost; the Retribution, though severely damaged by lightning strikes, survived and Jenner served on her some years later.

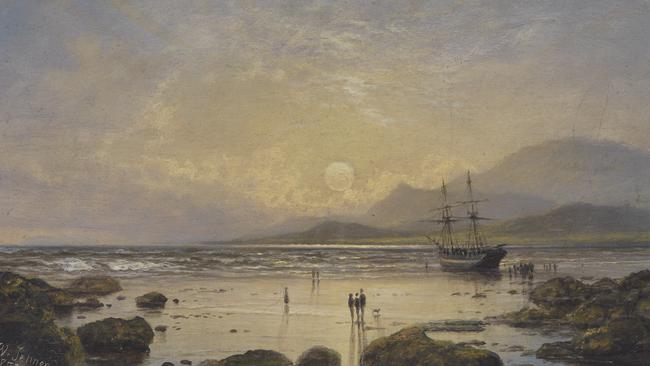

But this is not an exception in his work; Jenner seems to be drawn to the theme of the vulnerability of vessels, even in a picture like Ships at low tide with workers (c. 1882), where a large hull leans heavily to one side on the beach, deprived of its buoyancy and power. There is another beached ship in Seascape (1898), surrounded by tiny human figures in the moonlight, in a shallow bay at low tide. The scene here may be benign, but a similar subject appears much more menacing in Ship aground, Cornwall coast (n.d.).

Jenner is all too aware of the fragility of ships, however sturdy their construction, in the face of the violence of nature, and The Breakwater, Plymouth Sound (1883) shows what could easily have been the fate of the Retribution: massive timbers are shattered and splintered by rocks and waves while a handful of survivors clamber onto the rocks in the right foreground. Equally awe-inspiring although less explicit is Cape Chudleigh, Coast of Labrador (1893), which recalls two famous arctic exploration expeditions that were defeated when ships were crushed by pack ice.

The sublime ice-scape of this picture may remind us, but probably fortuitously, of Caspar David Friedrich’s The Sea of Ice (1823-24), which also depicts the destruction of a ship by ice in a radically inhospitable arctic setting. In Jenner’s composition, the mysteriously warm light on the horizon (apparently from a burning ship beyond the glacier), set against the cold moonlight bathing the ice, seems to point to another influence: such a play of warm and cool lighting is common in the landscapes of Joseph Wright of Derby.

Even a much less dramatic picture, however, such as HMS Victory at Portsmouth (c. 1881), is imbued with a deep sense of vulnerability and melancholy; for this is none other than Lord Nelson’s flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, where one of the greatest naval commanders in history died destroying Napoleon’s navy and saving England from invasion. No ship could have more glorious associations, and Jenner himself had served on her in 1855 when he first joined the Royal Navy. But even then she had long been retired from naval service and was used as a transport vessel.

The tone and subject of this picture inevitably recall Turner’s far bigger, grander and also more explicitly melancholy The Fighting Téméraire (1839), in which another great warship and veteran of Trafalgar is being towed away by a contemporary steam tug, against the background of a spectacular sunset, to be broken up for scrap.

Turner was no doubt a model for Jenner’s treatment of light and space, although we can also see the influence of other English landscape and marine painters; and interestingly, there is a distant echo of another famous Turner painting, Rain, Steam and Speed (1844) in Jenner’s much more modest Steam engine coming around the bend (1896).

The many pictures of English subjects that Jenner painted after he migrated to Australia, and in particular his accurate and detailed images of famous ships and coastal landscapes, suggest that he must have brought sketchbooks with him, as John Glover had done half a century earlier, but also that he presumably kept sketchbooks throughout his years in the Royal Navy, and made studies of subjects such as the ice banks at Cape Chudleigh.

Once in Queensland, he painted some of the first images of the new and growing settlements, not just in Brisbane but also up the coast of the newly separate colony. One such picture must be among the first views of Townsville (1900), already a busy harbour filled with steamships and lined with warehouses. Another, Queensland natives, the Currigee Oyster station (1897), shows oyster harvesting at a farm in Moreton Bay. And there are of course many pictures of Brisbane and the Brisbane River.

Jenner, like other 19th-century Australian artists from Von Guerard to Streeton, was aware of the destruction that was concomitant with the spread of the modern world into a formerly pristine land; the theme is most explicit in a small painting of a dead and charred tree trunk entitled A Martyr to Civilisation (1889). Interestingly, too, the speed at which the new was superseding the old, even in this very young settlement, inspired in him the same kind of melancholy we feel, for example, in Sydney Ure Smith’s etchings of old farm buildings at Windsor in the years just after the Great War.

But Jenner’s Slab cottage, Bowen Hills (1894) is almost a generation earlier, at a time when nationalistic hope for the coming Federation left little room for nostalgia. The picture confirms that Jenner’s interests and priorities were in many respects different from those of the Heidelberg painters of Sydney and Melbourne, who happened to be both the best and the most historically significant artists of their time in Australia.

And yet his work reminds us that it is possible to be an artist of real distinction without being “historically significant”, while individuals credited with playing an important role in their own day may not always stand up to later and dispassionate examination.