‘Before I was an artist, all I ever saw were the tracks on the ground... now I see the beauty’

Albert Namatjira’s landscapes deserve to be considered as an intercultural phenomenon because the artist not only learned a new style of painting but a different way of seeing the world.

When Albert Namatjira was introduced to the western art of landscape by Rex Battarbee in the late 1930s, it was not just a new style of painting that he learned, but an entirely different way of seeing the world, almost as profound in its implications as the way that learning to read and write transforms and extends the capacity and functioning of the mind.

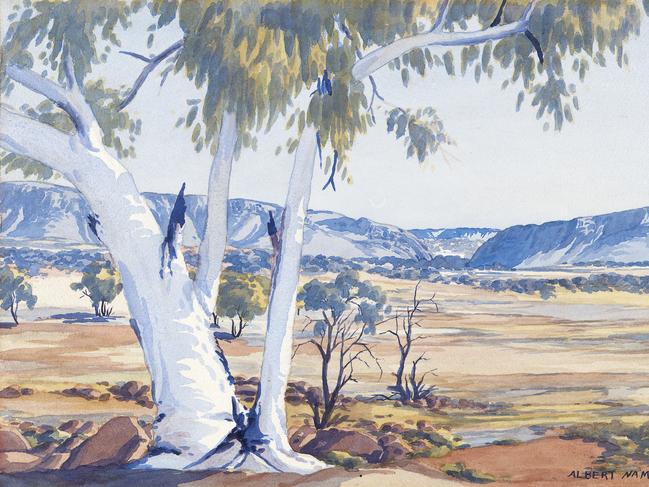

He learned the technique of watercolour and a style that was most directly derived from that of Hans Heysen, who was generally recognised as the greatest exponent of Australian landscape painting since the Heidelberg period. But he was also introduced to the more fundamental implications that underlay all landscape painting, including in the Chinese tradition, but more particularly in the western one because of its systematic development of perspective theory.

Landscape presupposes a viewer looking out at a natural scene; it generally assumes that the viewer is looking straight out towards the horizon, which in a painting corresponds to the level of the viewer’s eye, so that the line of the gaze is horizontal. But the most important implication of this model is that the viewer is outside or separate from the natural world that is being observed.

This distinguishes the viewing or knowing subject from the world which is the object of the gaze; and it sets up a concomitant dialogue between subject and object, between individual and transcendence. Such a fundamental distinction is the basis for a properly aesthetic engagement with nature, just as it is the basis for all spiritual ideas of the relation between the individual self and a greater or impersonal reality.

Traditional Aboriginal culture does not know this fundamental distinction; on the contrary, it is a vision of the world in which the individual is identified with the land and with the ancestors who have lived in the same place. Since there is no individual self, there is no question of transcendence of that self; and since humans are identified with the land, there is no outside view of the environment.

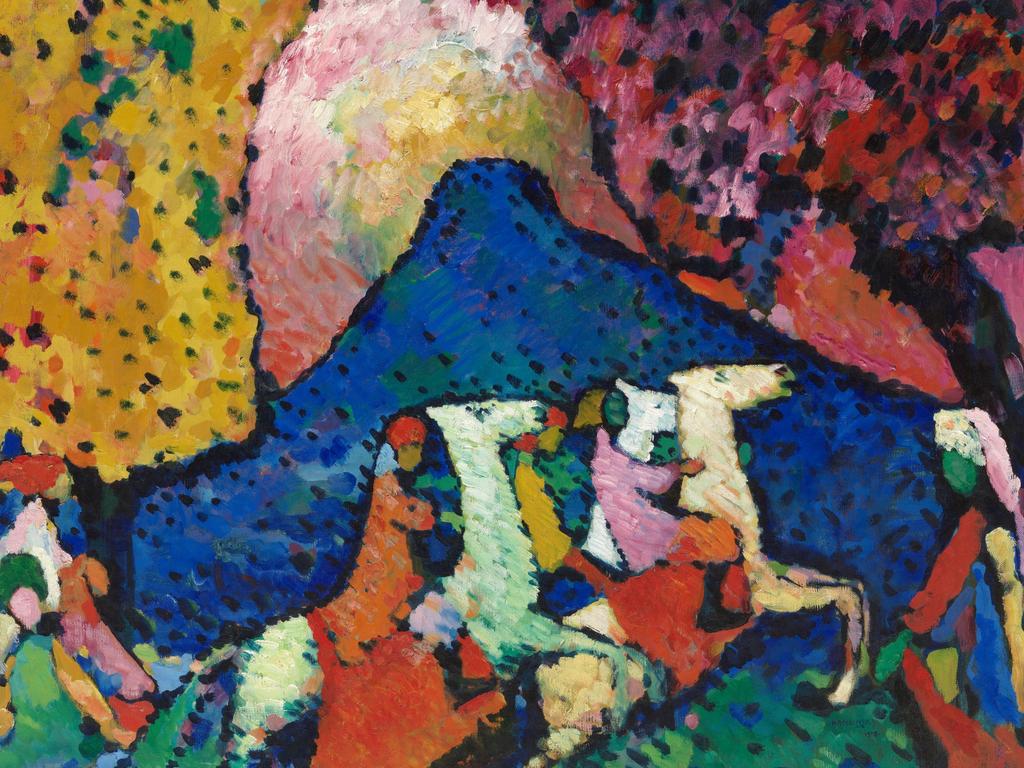

This is what makes Namatjira’s work so interesting, and it deserves to be considered more closely as an intercultural phenomenon, just as we might think of the Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) – Lang Shining in Chinese – painting in a mixture of eastern and western style in 18th century China.

An exhibition panel quotes a telling remark by Namatjira himself: “You know, before I was an artist, all I ever saw were the tracks on the ground. We didn’t have time to look up at all. The tracks were our life, eyes down all the time. But now I see the beauty and it’s changed my life completely.” These words epitomise the contrast between a life intrinsically bound up in the land, and the kind of liberation that comes from being able to look at it and understand it, which we can only do when we recognise our separateness as viewing subjects. The eyes down on the ground are comparable to those of a peasant who never looks up from his furrow, or the hunter who never looks up from undergrowth where he is searching for game.

The people with their eyes down all the time are indeed intimately involved in their natural environment and possess a deep knowledge of it, but they are also dominated by desire, primal need and the necessities of survival; it is only standing up, looking out and discovering ourselves as separate from nature that then allows us to imagine another kind of communion with the world around us.

Both Namatjira’s discovery of an aesthetic perception of nature and his skill at watercolour are illustrated by his treatment of the fall of light on the trunks of the great eucalypts which usually occupy his foregrounds. From the technical point of view, we can see that he understands the way that watercolour inherently works from light to dark – the reverse of oil painting – and that the lightest parts of the composition are constituted by areas of the paper that have been left unpainted; it is thus an art that demands forethought and presence, and is not easily amenable to reworking.

From an aesthetic point of view, the fall of light on tree trunks – unimaginable in traditional Aboriginal art – reflects the specificity of the viewer’s gaze, both in space and in time, since such light effects are constantly changing. No doubt it was something Namatjira took great pleasure in, since it epitomises the experience of beauty which this kind of painting helped him discover.

Most of the exhibition is, however, filled with countless later members of the Namatjira family, and their understanding of the original patriarch’s work is immediately clear in how they treat the fall of light on tree trunks. For this remains a standard element of the later compositions, but in most cases it becomes a mere stylistic mannerism, copied, as though in a game of Chinese whispers, with little or no sense of its original meaning. And this fossilised motif is set in the foreground of landscapes that have no sense of the light or atmosphere of which it was originally the most conspicuous manifestation.

The Art Gallery of South Australia, as it happens, has a pair of pictures that sum up this development: Ghost gum, Central Australia (1956) by Namatjira, hung below the far less sophisticated West of Alice Springs, near Jay Creek by Edwin Pareroultja (1950s). AGSA also has its annual survey of Indigenous art, Tarnanthi, as well as a survey of Vincent Namatjira, who won the Archibald Prize in 2020.

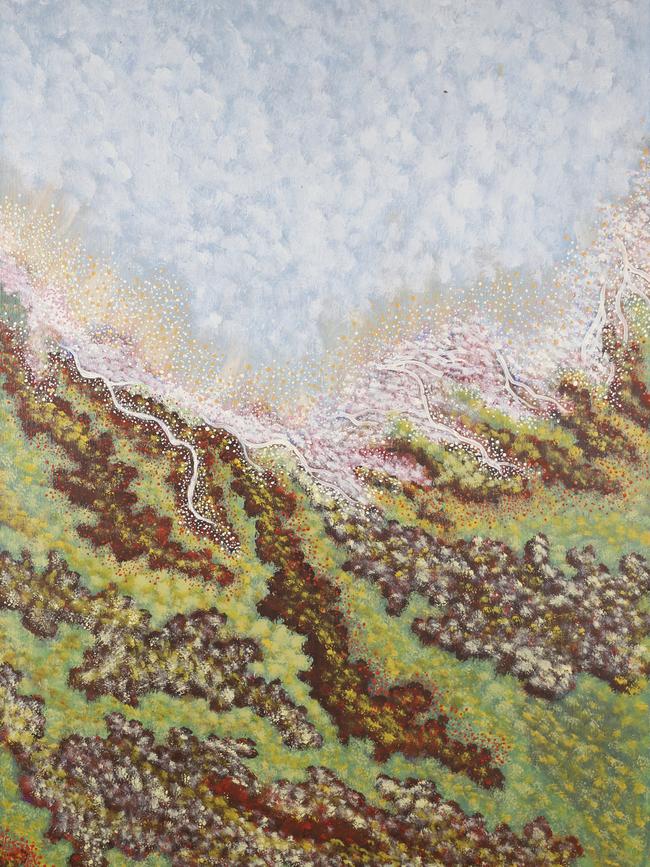

Tarnanthi is, as one would expect, a very mixed bag and reminds one a bit of a school show in which everyone has to be hung regardless of the difference in standard between the works. There are many dot paintings, as well as figurative ones, and the trouble with these two categories is usually quite different; that is, the dot paintings tend to be somewhat slick and mechanical, while the figurative ones can be naïve and clumsy.

Sometimes the naïve works can be striking, as with three big red monochrome pictures by Motorbike Paddy Ngale, which represent an improbable crowd of figures and motorbikes to depict the mustering work of the artist’s forebears.

In the dot mode, Dulcie Napaltjarri Nanala stands out particularly for Wilkinkarra, a painting of an ephemeral desert lake in country that her ancestors and those of her community used to inhabit before their move to Balgo Mission in the 1940s. Several other painters working with dots have a sense of design and even movement, but the work tends to be repetitive and formulaic. One who is of greater interest than most is Bugai Whyoulter, whose paintings inspired by the Canning Stock Route occupy a whole room; the first four of these from the left have a dramatic sense of organic life and movement, although they work best as a suite and the later pictures in the sequence do not have much presence when taken alone.

A third Indigenous exhibition takes us back to Sydney and to the State Library, to a small but significant display of very old artefacts collected in the early days of exploration and settlement, which have been lent by the British Museum and other British institutions.

Of these, one of the most impressive is a shell fishhook made from a ring of the turban shell. The technique of fishing with a line and hook is considered relatively recent, dating to less than a millennium ago, and it is mainly found in southeastern Australia, though not in Tasmania, where the Indigenous population seems to have largely stopped eating fish some thousands of years ago. They are also found on the north Queensland coast, but not along some 1000km of intervening coastline.

One question about these fish hooks is of course where they came from. It has been suggested that they are evidence of some contact with Polynesian traders (indeed these hooks were originally catalogued as from Tahiti), which might explain their separate introduction in two different areas. They were not used with bait attached, but with bits of chewed shellfish cast into the water as what fishermen call “berley”; attracted by the smell, the fish seem to have mistaken the shiny shell hooks for something edible.

The introduction of the fish hook must have significantly increased the fish catch in the Sydney region and thus probably the local population, but most interesting of all is the fact that line and hook fishing was restricted to women, while men – in a society where gender roles were strictly differentiated – continued to fish, as they had always done, with spears.

The earliest settler accounts write of women constantly out on the harbour in their bark canoes; it would be interesting to know what proportion of the total catch was taken by women as compared to men, and whether this made any difference to the social relations between the two sexes.

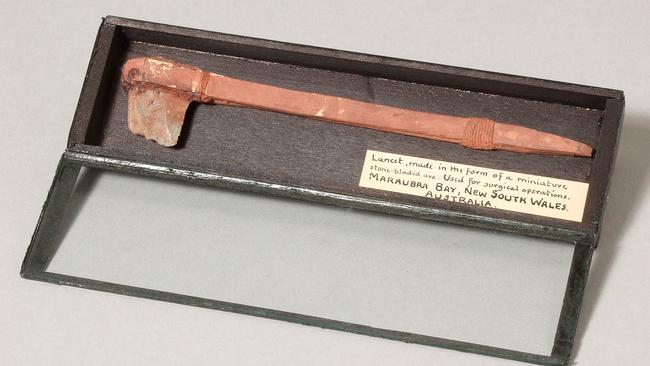

Some of the other artefacts are primarily associated with women, such as string bags and a small bark workbox, while others, largely weapons such as clubs and shields, of course pertain to men, as well as heavy tools such as stone axes. One particularly interesting and rare object is described as a “lancet” which must refer to its function rather than its form; it may have been used for ritual scarification in initiation ceremonies.

In many of these artefacts, including axes with wooden handles and the fish hooks with twine still attached, organic elements that would normally have perished over the centuries have been preserved.

It may seem strange and almost paradoxical that these should be among the oldest surviving artefacts from a culture which, as we are constantly reminded today, has survived almost unchanged for tens of thousands of years. But that is because many objects are not saved or stored in such cultures, but used and replaced with identical things. There are no buildings in which they could be preserved but, almost more fundamentally, there is no need to preserve them since they are going to be replaced with identical copies. The idea of preservation only arises when we are no longer using a given technology but moving on to another one, and when we are conscious of the change we are undergoing.

These items were collected, of course, not by the Indigenous people but by Europeans curious to gather samples of the cultures of peoples at an earlier stage of technological development.

Today there is much talk of repatriation of artefacts and objects from other cultures, but some Indigenous people recognise that it is only because these items were collected and preserved in Western museums that we know of them at all.

Watercolour Country: 100 works from Hermannsburg, National Gallery of Victoria, until April 14.

Tarnanthi, Art Gallery of South Australia, until January 21.

Wadgayawa Nhay Dhadjan Wari, State Library of NSW, until January 28.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout