Valiant attempt to combine activism and artistic endeavour misses the mark

It’s difficult for Hoda Afshar’s images to compete with the many vivid and painful photographs that have come out of protests in Iran, whether shots of demonstrators taking off their headscarves or women cutting their hair.

In September last year, a young woman named Mahsa Amini – known to her friends by her Kurdish name Jina – died in custody after being detained by Iran’s morality police for not wearing her headscarf correctly. She was arrested on the 13th by one of the “guidance patrols” (Gasht-e Ershaad) and was allegedly beaten so severely that she fell into a coma and died on the 16th.

Her death provoked waves of protest throughout Iran, first in Kurdish communities and gradually spreading to the whole country. More people, especially girls, were reportedly killed and many were arrested. Enormous demonstrations were held daily in all the main cities of the country, in spite of brutal repression by the authorities. At night, voices rang out from apartment blocks crying “death to the dictator” and “death to Khamenei”, referring to the clerical Supreme Leader of the country. In the streets below, government thugs tried to work out where the voices were coming from and yelled back threats.

Anger rapidly spread from young women and men in the cities to people of all classes and ages. Even many conservatives were horrified by the idea of killing any young woman in the name of enforcing her chastity and protecting the morality of the nation. And the anger went well beyond the state’s morality laws and exploded into an increasingly widespread and vocal rejection of the whole regime, with its incompetence, repression, corruption and the militaristic adventuring which we are witnessing today in Gaza and the whole region.

The protest movement, with its inspiring slogan “zan, zendegi, azaadi”, woman, life, freedom, even began to spread to the critical sectors of the population whose support no modern government in Iran has ever lost with impunity, the bazaar (the shopkeeping class) and the oil refinery workers. By the middle of winter, the movement (“jombesh” in Persian) was beginning to be referred to as a revolution (“enghelaab”). Some hoped that the regime of the mullahs might actually be overthrown.

Unfortunately, the rule of the old men with long beards – although perhaps ultimately doomed by the demographic wave of younger educated people with an entirely different outlook – is propped up for the time being by the Revolutionary Guard, which is something like a combination of the Waffen SS in Nazi Germany and the Mafia: a parallel army with an ideological rather than national mission, and at the same time an organisation with economic interests throughout the nation.

Perhaps if the aged and unwell Supreme Leader Khamenei had died at the right time, the whole edifice might have crumbled. But he held on and the protests eventually died down and the regime proceeded to purge students and academics and others who had supported the uprising. So the state eventually won this battle, but has undoubtedly sustained serious, irreversible – and perhaps ultimately fatal – damage to its credibility in the eyes of the people.

As the protests extended month after month, it began to be increasingly apparent not only that the old men with their turbans and beards would do anything to suppress opposition, but also that they considered that the battle over the hijaab, the headscarf and associated dress rules, had to be won at any cost. Making women cover their hair was not, as it turned out, merely an Islamic custom that they sought to maintain, but somehow the very foundation of their whole vision of society and indeed of their power over the population. Repressing and controlling women was revealed as the cornerstone of the Islamist regime.

Meanwhile, International Women’s Day in March 2023 completely ignored the most important and vital women’s movement actually taking place in the world today. IWD ran the bland slogan “embrace equity” (and we can look forward to an equally bland “inspire inclusion” next year). UN Women Australia had the laughably inept “cracking the code”. Why did no one think of adopting “woman, life, freedom”, which arose spontaneously from a real movement of real people and was not concocted by a team of brand consultants in a rich, safe metropolis somewhere in the western world?

In Iran a year later, the authorities were on high alert in September, in case the anniversary of Jina Amini’s death – and the anniversaries of others who were killed in the subsequent repression or executed after show trials – provoked renewed demonstrations. But they were also struggling to find a way to contain what seems to have become an increasing disregard for the hijaab rules.

The regime had suspended the “guidance patrols” in order to avoid further public relations disasters which, in the age of social media, spread instantly to the whole country. Instead, they came up with another group of morality custodians who were meant to be stationed in the metro system and advise girls to wear their headscarf correctly or potentially prevent them from using the underground system if they did not comply. And a couple of months ago the Iranian Parliament passed a draconian new “bill to support the family by promoting the culture of chastity and hijaab” which prescribed prison sentences of up to 10 years for violation of chaste dress standards.

And then, just a couple of weeks ago, a new catastrophe: a 17-year old girl, Armita Garavand (or Geravand), was allegedly fatally beaten by the new morality enforcers. She boarded a metro train on October 1 and according to witnesses, was violently assaulted by an officer for failing to wear a headscarf.

Moments after this, Armita can be seen, on exterior footage that was published, being carried out of the carriage and onto the platform by her friends; Amnesty International analysis (published on October 6) shows that the platform footage has been fraudulently tampered with to cut three minutes and 16 seconds from the sequence and erase the time during which the confrontation inside the carriage took place. Video footage of the events inside the carriage has been entirely suppressed.

Armita was taken to hospital where she lay in a coma until after three weeks she was said to be brain dead; she died on October 28, and her funeral ceremony was apparently watched over by security forces and plainclothes agents, dreading a renewed wave of protests. The pathos of this new young life that has been lost is all the more tangible because many photographs of Armita, as well as information about her life, can be found online. A vivid selection of pictures is still available on Instagram (armitagaravand1).

The oppression of women in Iran, now revealed as both the ideological foundation and simultaneously the Achilles heel of the military-theological complex that runs the country, is the background of the first important set of work that we encounter in Hoda Afshar’s exhibition (and accompanying book) at the Art Gallery of NSW. It is a series of large-scale black and white photographs of Iranian girls, mostly seen from the back, plaiting each other’s hair or holding or releasing doves, which is said to be associated with funeral ceremonies in Iran.

Some of these images are touching, and almost memorable, but they have difficulty competing with the many vivid and painful photographs that have come out of the movement in Iran, whether shots of demonstrators taking off their headscarves, women cutting their hair, or even – on Instagram and other media, such as the BBC Persian service – the many sad images of lives cut short. In the end, Afshar’s series feels somewhat vapid, lacking in conviction and perhaps even evasive.

This impression is confirmed by her vociferous support for the Palestinian cause on her Instagram page where she refuses to acknowledge the barbarity of Hamas’ terrorist attack on women and children in Israel which they knew very well would plunge their own people into a nightmare. What is especially dubious about her stance on this question is that Hamas is a tool of the Islamist régime in Iran and the attack on Israel was a cynical ploy to derail the normalisation of relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia.

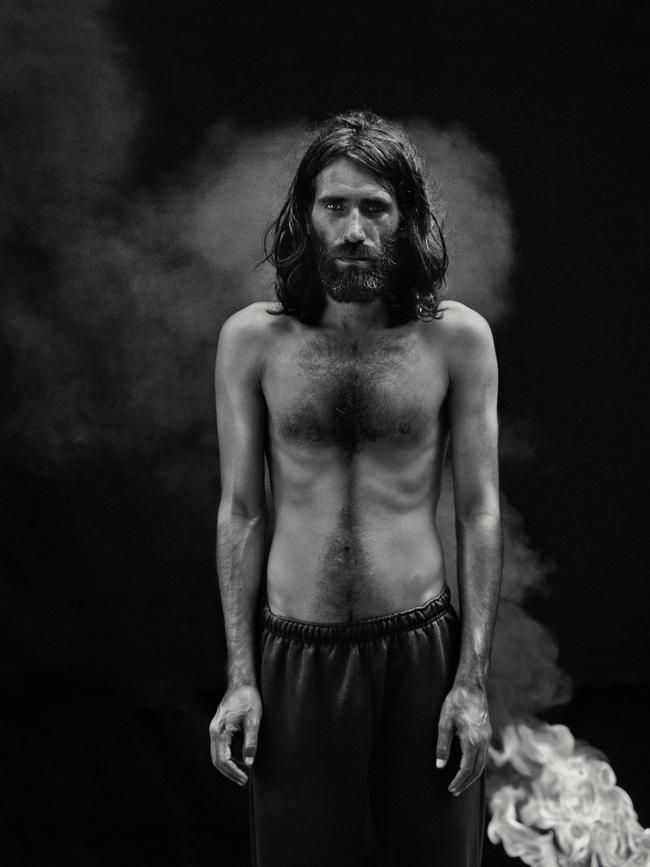

Afshar’s best work is in the documentary mode. The single most striking photograph in the exhibition is the frequently-reproduced portrait of Behrouz Boochani, who is also the subject of a video work in which he is shown walking down to the sea on Manus Island, while on a second screen native children look up at the camera in innocent wonderment.

The most memorable series in the exhibition is Behold (2016), which came about, as the artist has said, almost fortuitously, when she met a group of homosexual men in an unnamed city in Iran. They were tolerated as long as they remained invisible, and as she says, they somehow longed to be seen and recognised. So they invited her to photograph in the bathhouse where they could meet and congregate in secret.

The resulting pictures are striking because they are so painful. Classical Persian poetry is filled with celebrations of beautiful youths with ruby lips and tulip cheeks, but there is no such idyllic and romantic eroticism here – nor indeed were sexual relations between adult males ever romanticised. These are pictures of a kind of hell of unhappy, forbidden and proscribed desire which nonetheless must find some outlet, and a place of companionship in which unhappiness can be assuaged.

Perhaps the least satisfying series is Agonistes, where nine strangely abstracted quasi-portraits are shown with a projection of close-ups of eyes and other details, and a loud soundtrack of the subjects speaking which unfortunately impinges on the surrounding spaces. The abstraction of the portraits is explained by the fact that they are 3D digital prints based on hundreds of separate photos of each head, which have then been rephotographed.

The remainder of the exhibition is made up of images of Iran and of Iranian people, many evocative, others enigmatic to those who have not been to Iran, like a picture of Yakhchaal or an ice-house in beehive shape, which allows ice to be preserved through the heat of summer, or a Tower of Silence (borj-e khaamushaan, literally tower of the silent ones), one of the structures, high on a hill, in which until quite recently the Zoroastrians would expose the corpses of the dead to be eaten by vultures.

A final series, shot on the island of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, juxtaposes shots of women forced to wear face masks – the islanders are ethnically Arabs – with images of strange, evocative cliffs and rocks eroded by the sea wind. The suite as a whole, however, has little impact and it is only the black and white images that have a sense of tonal structure.

One is left, at the end of the exhibition, a little unsure why a photographer of Afshar’s level of achievement is being given a survey at a state gallery, and why so lavish a publication has been produced for an oeuvre that is ultimately so uneven.

Hoda Afshar: A Curve is a Broken Line, Art Gallery of NSW, until January 21.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout