One eye on transcendence

An exhibition about the Russian painter at Art Gallery of NSW reminds us that hope can prevail even under difficult political circumstances.

When we look back over the history of modernism, it is clear that its most dynamic phase was in the half-century or so before the Great War, intensifying and accelerating in the decade or so leading up to the outbreak of conflict. This was the period that produced impressionism, neo-impressionism, various forms of post-impressionism, symbolism, fauvism, expressionism, cubism, futurism, constructivism, orphism and abstraction; the war years gave us dada and its aftermath surrealism.

In hindsight, this hectic and restless energy seems like an anticipation of the coming crisis, like ants scurrying around frantically before a storm, and it epitomises the way that art registers and expresses feelings and deep social currents of which contemporaries are not yet conscious but which they are already experiencing as a pervasive but indefinable mood, whether of optimism and conviction or doubt and malaise.

Numerous factors led to World War I, including political rivalries and diplomatic failures, economic interests and nationalist ideologies and strategic anxieties unleashed by the unification of Germany and the Franco-Prussian war at the beginning of this fateful half-century. But there were also deeper and longer-term intellectual and spiritual factors that find expression in the explosion of modernist movements.

The 19th century recalls the 17th as an age both of scientific progress and of renewed religious fervour; already in the 17th century there had been friction between two ways of looking at the world, but that friction was much more intense in the 19th century, and new discoveries about the geological age of Earth and particularly the evolution of man were felt by many to be incompatible with scriptural teaching, leading to a new kind of polarisation in which some abandoned faith and others denied science.

Radical materialist and atheistic philosophies had precursors in the 18th century but now became more overt and more widely embraced, whether in the positivism of Auguste Comte or the economic materialism of Karl Marx. But, simultaneously, new forms of spiritualism arose, in particular one that is of enormous importance for the history of art, the Theosophical movement founded by Russian Madame (Helena) Blavatsky in New York in 1875. Almost all significant abstract art, notably that of Kandinsky, was shaped by this philosophy.

The Theosophists were also influential in the rediscovery of several Oriental spiritual texts that have since become standard references, such as the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali and the Tibetan Book of the Dead – and surprisingly, it was the Western interest in these texts that in turn provoked a re-evaluation of them in their own cultures of origin, just as it was Edward FitzGerald’s translation of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat that, strange as it may seem, reintroduced this poet to Persian readers who had all but forgotten his existence.

As the rise of spiritualism and occultism should suggest, all was not quite well with the ideology of science either. On the face of it, this was the golden age of scientism as an outlook and positivism as a philosophy; the word scientific acquired the fundamental connotation of soundness and progressiveness that we now associate with green or ecological. Anything from a system of education to diet or clothing could be endorsed as scientific. Yet the objective and rational view of the world implicit in science was increasingly questioned both by the “new age” beliefs of the time and by all the various directions of modern art.

Modernism in art can in fact be understood only within an art-historical arc that is also inherently a part of the history of modern civilisation since the Renaissance. The discovery of volume and space we see in Giotto and the early Renaissance is the beginning of the imaginative articulation of the objective world of science; the modernist movements in the early years of the 20th century are a kind of deconstruction of that vision, most obviously cubism, which takes apart the axioms of objective vision.

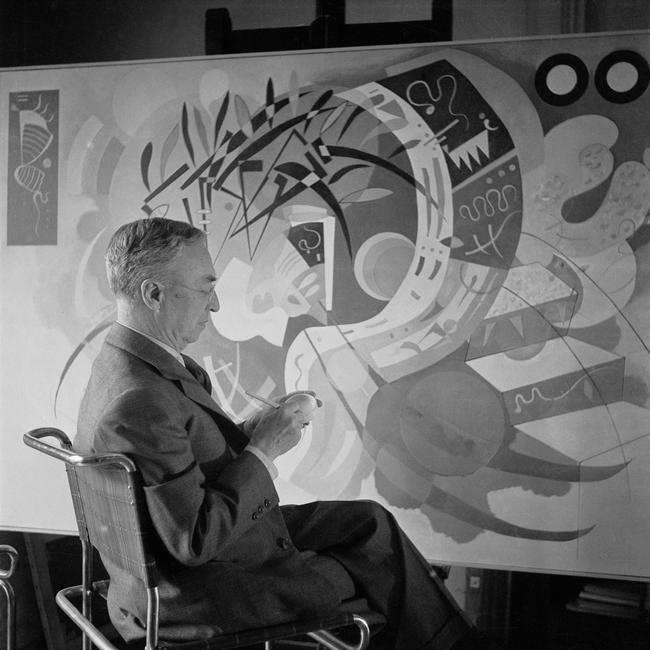

The work of Vasily Kandinsky (1866-1944) offers another perspective. It is at the Art Gallery of NSW, which has barely had a significant exhibition since Matisse: Life and Spirit two years ago – something almost incomprehensible for a state gallery – but like that exhibition, this one also has been brought in from another institution.

First presented under the same title at the Guggenheim in New York in 2021-22, the exhibition is accompanied by the original New York catalogue. The AGNSW, whether from laziness or because it is trying to save money, has not taken the trouble to produce its own version, even though the Sydney exhibition includes just more than half the works shown in New York. The publication thus includes more than 40 pictures that are not in Sydney and does not constitute a record of the actual exhibition.

Kandinsky was born in Russia into a well-to-do family, studied law and economics at university, and seemed destined for an academic or professional career; but several experiences, including an encounter with one of Monet’s Haystacks, Wagner’s music and even a period spent in the ethnographic study of Finno-Ugrian peasants, seem to have led him to a career in art. In 1896 he went to Munich to study and after a period of alternating between Russia and Germany, and travels to a variety of places including Tunisia, he eventually settled there in 1908.

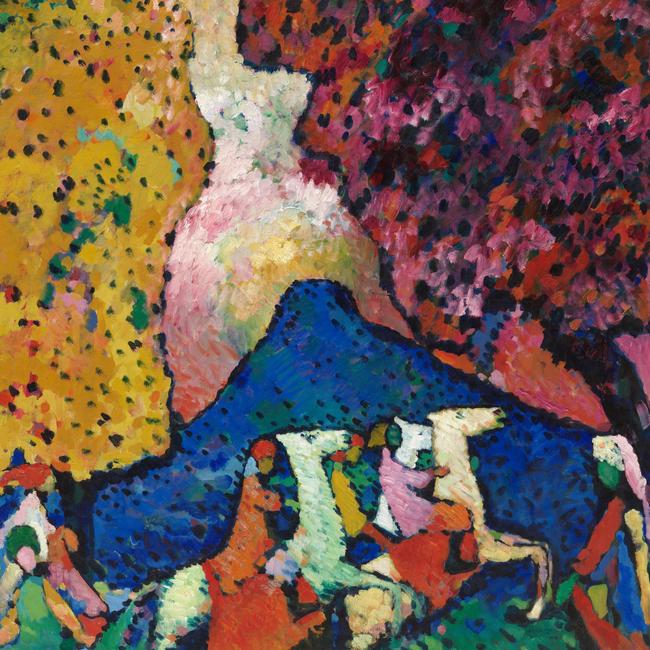

He became associated with the Blaue Reiter movement and was friends with Franz Marc and others. It is here that his distinctive vision emerges with the energy that makes his early paintings so appealing. They are landscapes, but simplified form, dynamic composition and chromatic intensity make pictures such as Landscape near Murnau with Locomotive (1901) emblematic rather than literal. In Sketch for Composition II (1909-10), these pictorial elements become even less literal and more abstract: recognisable landscape and figurative elements still abound, including a leaping horse recalling Marc, but forms, with black outlines like stained glass, are mainly deployed to evoke motion and energy, and colours are juxtaposed to exploit the aesthetic energy of complementary and other effects.

In these paintings we can feel the emergence of a spiritual and quasi-mystical sense of the world and of the life of nature, and in other circumstances one could imagine a painter such as this gradually evolving over the course of his life as he quietly explored his intuitions about life, being and consciousness.

But the historic dynamism and instability that had helped bring this vision into existence also would condemn Kandinsky to a life constantly buffeted by social and political vicissitudes.

The happy years in Munich were brought to an end by the outbreak of war in 1914, forcing him, as an enemy alien, to return to Russia, where he had to try to re-establish himself in a less congenial artistic environment.

Then in 1917 the Bolshevik revolution deprived Kandinsky of his independent income. A few years later it became apparent that the communist state was no friend to modernist art, let alone to spiritualism. So, in 1921, he returned to Munich and in 1922 joined the Bauhaus; but in 1933 the Nazi party, which also hated modernism, forced the Bauhaus to close, and Kandinsky left Germany for Paris. Then the Germans occupied Paris, although fortunately the artist lived to see the city liberated before his death in 1944.

The paradox of Kandinsky’s work, then, is that while we might expect a spiritualist vision to be inherently concerned with perennial and timeless themes, his work is also shaped by the changing times and environments in which he lived.

We can easily see, for example, the joyous eruption of energy in the paintings executed before the war, even when it is frequently counterpointed by intimations of drama or menace, as in Improvisation 28 (1912) or Landscape with Rain (1913). The same combination of energy and menace can be felt in the dramatic pre-war paintings of Marc, who sadly was killed on the Western Front in 1916.

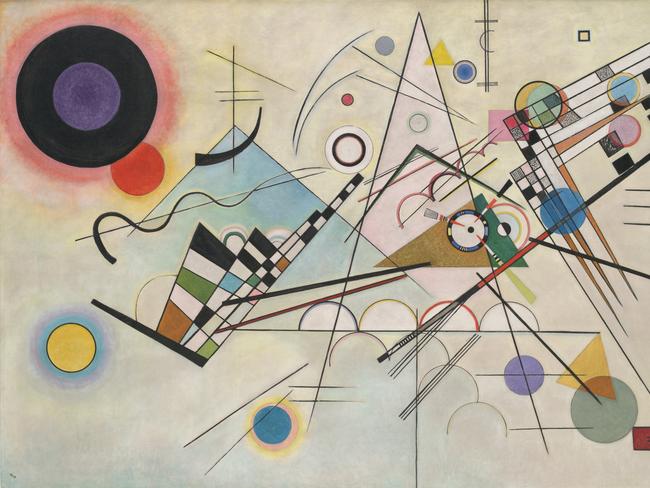

After the war, the painterly density, chromatic richness and powerful sense of movement disappear entirely. In Composition 8 (1923) we are presented with a disembodied world of lines and geometric shapes. It is as though an organic vision of the world had been replaced with a mechanical and clockwork one, as though we had left nature and entered a factory. Instead of a contest between vital energies, creative and destructive, we seem now to be witnessing a dispassionate game of impersonal forces. No doubt this change reflects both Kandinsky’s sense of the post-war reality and the geometric interests of the Bauhaus, leavened by a whimsy borrowed from his friend Paul Klee. Yet above all this restless movement hangs the circular form that evokes wholeness and stillness.

There are further changes after his move to Paris, where at first his style met with general incomprehension. He now encountered the surrealists, whose ascendancy soon would be brought to an end by the German occupation, and the biomorphic motifs that appear in his work suggest the influence of Miro and Jean Arp. In Varied Actions (1941) we see another change: the mechanical forms and their restless action have been replaced by largely biomorphic forms that seem to be suspended on a green-grey background like the sea, here again unlike the airy lightness of the background of Composition 8. Vertical Accents (1942) has a few inorganic forms sparsely scattered across a similar sea-like background.

Around the Circle (1940), the picture that has given its title to the exhibition, combines linear and biomorphic forms floating against a flat, very dark background like the night sky.

The elements in the composition have movement and energy, but neither like the early organic style nor the middle period mechanical forms; these are not lines and diagrams but flat patterns, like cutouts; sometimes they remind us of flags or banners. Perhaps, if the early organic forms evoked a world of living nature and the later disembodied lines suggested impersonal historical forces, these new patterns speak of an organic yet also social reality.

In any case, this strange dark world is dominated by an enormous circular form that it is impossible not to read as an eye, especially with the smaller yellow circle, which acts as a highlight on the pupil. Why is this eye staring at us? It would be useless to ask Kandinsky, for true artists are always pursuing intuition beyond the frontier of what they know or can articulate in any other way. But on the lower left is a motif that seems easier to read: three steps lead to a landing from which a door opens on to a night sky, and in the sky hangs a pale blue full moon, a promise of transcendence, even under German occupation.

Vasily Kandinsky: Around the Circle, Art Gallery of NSW to March 1.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout