Review, Queensland Art Gallery’s Still Life Now and Geelong Art Gallery’s A Tale of Two Cities

From the opening shots of a film we generally know whether it will be a thriller, science fiction, romantic comedy, crime picture, and so on. It’s a different matter when it comes to visual arts.

The concept of genre, discussed here a couple of years ago, is crucial to understanding the meaning of any kind of art, including literature and perhaps most obviously of all today, cinema. From the opening shots of a film we generally know whether it will be a thriller, science fiction, psychological drama, romantic comedy, crime picture, and so on. Apart from the overt content of these shots, pace, colour, lighting and music all serve to establish the category to which it belongs; and this category in turn helps us interpret what is going on; we know almost at once whether the story will end happily or not, whether we can expect deeper exploration of moral and existential themes or whether they will diverge into comedy or violence.

Genre thus gives us an idea of what to expect, and what has been called the “horizon of expectation” governs meaning, since any disturbance in the pattern of anticipation that does not fundamentally confuse the rules of the genre can be meaningful. These rules are conventions, and they vary according to the different focus of each genre. The great originality of Greek theatre was to start with the distinction of tragedy and comedy; the former was concerned with great themes and issues, treated in a serious and elevated manner, while the latter dealt with everyday life in all its foolishness and undignified banality. There will never be an obscenity or a hint of indecency in tragedy, and yet this is not because of prudishness, for there is conversely almost no limit to obscenity and scatology in comedy. The rules of decorum are not absolute but appropriate to each genre.

Still life was traditionally regarded as one of the most modest of painterly genres, since it dealt neither with human subjects nor, like landscape, with the grandeur of living nature, but only with the “dead nature” or “nature morte” in French, composed of picked fruit and cut flowers – things separated from the source of life – as well as human artefacts. Although it existed in antiquity, still life in the modern period, like landscape itself, emerged from a secondary role in history painting and took on a life of its own, especially in the 17th century.

Still life had subgenres like flower and fruit painting, luncheon or “breakfast” tables, and books, musical instruments and other works of human craft, even if all or most of these motifs could also be found in combination. It also had themes as different as the memento mori, allegories of the senses and the celebration of pleasure, although again these could be found in sophisticated combinations. The expression of the genre varied considerably from the 17th to the 20th century, and still has much to offer a contemporary artist.

This is why the Queensland Art Gallery’s Still Life Now sounded promising. In fact, although it presents a number of interesting and relevant works from the collection, its main shortcoming is including too many things that don’t really fit within the genre – one has to know how far boundaries can stretch – and which distract from the attention we should be giving to the relevant items. Particularly unsuitable is Deborah Kelly’s otherwise entertaining video work Beastliness, whose loud soundtrack invades and dominates the whole exhibition space.

The other problem is that few of the works accord their motifs the close and patient attention that gives the best still life its mysterious resonance, whether in the hands of Chardin in the 18th century or Morandi in the 20th. Still life is a genre in which we find our own experience mirrored in the objects of our feelings and even our appetites; here, all too often, motifs and the genre itself are merely used or instrumentalised to convey superficial and contrived messages.

Consequently the works that pastiche traditional still life of past centuries are tiresome, especially when produced with photography and digital painting applications rather than painting, while those which look afresh at things in a less self-conscious way are more interesting. Among these pieces, apart from the Cressida Campbell print of her studio and Jude Rae’s still life that echoes Morandi on a larger scale, employing gas bottles and other contemporary objects, perhaps the most memorable of all is an ostensibly humble set of black and white photographs of a turnip or radish-like root vegetable by a Japanese artist, Kozo Miyoshi.

These photographs do not conform to the traditional compositional format of still life, but they compensate for that by bringing a closer and sharper attention to their motifs than anything else in the exhibition. And just as Morandi’s groupings of simple bottles and jars can seem to echo the format and feeling of a history composition, these vegetables, sagging in incipient decay, begin to look like human flesh, with taut thin skin enclosing a swelling internal mass.

The other notable photographs are by Justine Cooper, part of a series entitled with some irony Saved by Science, for her subjects are essentially zoological, ornithological or entomological specimens that have indeed been preserved through processes of taxidermy and taxonomy, but which are of course dead and perhaps endangered by the progress of human technologies. Of these images the two most striking hang side-by-side: a pair of amphibian skeletons suspended in bottles of formaldehyde, and a storage cupboard opened to reveal the gigantic skull of a flesh-eating dinosaur.

Far from Brisbane, another small exhibition of interest is Geelong Art Gallery’s A Tale of Two Cities, whose Dickensian title here refers to Sydney and Melbourne rather than London and Paris. This is a selection of etchings from the bequest of Colin Holden (1951-2016), a remarkable man who was a scholar of ancient Syriac, an ordained Anglican priest, and an exceptional connoisseur of prints, from the works of Giambattista Piranesi, which he catalogued for the State Library of Victoria and the University of Melbourne to those of modern Australian artists. His obituary by Shane Carmody can easily be found online.

The appreciation of any kind of art is enhanced by some understanding of the process, and as I have observed before, this is particularly true with printmaking, which remains obscure to many people. Essentially a print is a multiple impressed onto paper from an inked block or plate. One of the most basic distinctions is between relief prints, like woodcuts and linocuts, where the image corresponds to what remains of the original surface of the block when the rest is cut away, and intaglio, where lines correspond to grooves incised into a plate.

Of intaglio forms, the earliest variety is engraving, in which the design is directly cut into the plate with a burin; in the later method of etching, the plate is covered with an acid-proof varnish, then the design is scratched into this surface and the plate submerged in acid, which bites into the metal wherever its protective layer has been removed. After this the plate is cleaned, inked, wiped and printed onto damp paper in an etching press.

The greatest master of etching was Rembrandt, but there was an important revival of interest in the later 19th and the first half of the 20th century, and the medium appealed to Picasso, Matisse and other modernists. In Australia, there was a particular surge of creativity in etching between the wars, extending, to the important post-war figures of Fred Williams and George Baldessin. Other forms of printmaking were popular at the same time, like the linocuts practised by Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme, also shown at Geelong last year.

This exhibition concentrates on a handful of the most significant etchers active in Sydney and Melbourne a hundred years ago, starting with Bridge building No. 1 (1924) by Jessie Traill (1881-1967). Traill, notable in many ways and the most important woman etcher in Australia, would later produce an outstanding series of prints of the building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge (1927-31). This structure, however, is less ambitious: Church Street Bridge which crosses the Yarra connecting Richmond with South Yarra.

Most of the other Melbourne prints are by John Shirlow (1869-1936), a self-taught etcher who built his own press and worked on the plates en plein air, rather than in the studio from sketches; this is what gives images such as Queen’s Wharf (1918) and Melbourne From The West (1919) a fresh and spontaneous quality, with a combination of naturalism and a love of evanescent effects inspired by Whistler. In other pieces, Shirlow makes use of different intaglio techniques to achieve stronger tonal effects for evening subjects: thus Twilight, River Yarra (1919) is executed in mezzotint and Evening, Collins Street (1923) in etching and aquatint.

The third Melbourne artist is AH Fullwood, the subject of Gary Werskey’s Picturing a Nation (2021) and an important contributor to the Picturesque Atlas of Australasia, the subject of an exhibition at the National Library of Australia (reviewed 10 April 2021). His images of Melbourne are lively and convey the confident spirit of the time, but they retain a quality of reportage compared to Shirlow’s greater range of poetic feeling.

The Sydney half of the show is dominated by Sydney Ure Smith (1887-1949), one of the most important figures in Australian art between the wars. He published the magazine Art in Australia (1916-42; his son Sam Ure Smith later started a new series under the title Art and Australia from 1963) as well as the leading women’s magazine of the time, The Home (1920-42), which covered aspects of modernist art, and numerous art books; he also ran an important advertising firm which employed many artists and was a trustee of the Art Gallery of NSW.

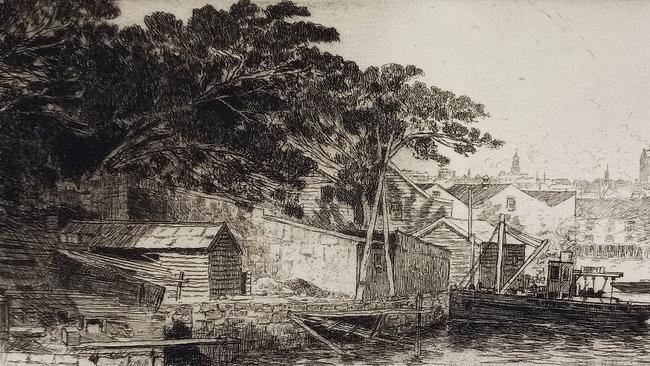

At the same time, Ure Smith was one of the most talented etchers in the history of Australian art, with an acute eye for detail but also, as we can see in images such as Darling Harbour from Balmain (1915) or Gore Bay (1918), the ability to subordinate the incidental to an overall sense of composition and a Whistler-like feeling for the poetry to be found in industrial sites and subjects.

This little exhibition gives a sense of the range of expression contemporary printmakers found in their urban subject-matter: at once celebration and pathos, hope and nostalgia; John Shirlow is quoted on a panel as declaring “I’ve tried to show the beauty of unloveliness”. Melbourne, of course, was still a young city, perhaps three generations old; Sydney, at twice its age, had its roots in the 18th century, and there was already a consciousness of the “old Sydney” slipping away. But above all these works reflect a growing sense of historical depth, that Australian cities were no longer the first things ever built on the land, but developing into organic urban systems in which modern lives were woven into the fabric of those who had come before us.

Still Life Now, Queensland Art Gallery/GoMA, until February 19. A Tale of Two Cities, Geelong Gallery, until March 13.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout