Grim fairytales the art of darkness

Animals often featured as the ‘stars’ of historic fables that revealed the disturbing depths of the human character.

It may come as a surprise to realise that our modern interest in fairytales begins in the age of Louis XIV in France. We think of French classical literature in the 17th century as imbued with rational lucidity and, on the face of it, that is true: language had perhaps never been used – certainly not in modern times – with such analytical acuity and precision, either in philosophical reasoning or in dissecting the sentiments of the human heart.

But the result of this dissection was often to show how dark and irrational the workings of our hearts and minds could be. Blaise Pascal sought to show the limits of reason, and the paradox that reason could discover its own limits. The Duc de La Rochefoucauld, in his celebrated Maxims (1665), revealed human judgment as constantly distorted by self-interest and the covert influence of egoism.

So it is perhaps not surprising if the same period had a particular fondness for stories that reveal dark, irrational, mysterious or sometimes merely whimsical aspects of human experience. The ancient myths themselves, the basis of French classical tragedy – such as Racine’s Phèdre (1677) – often deal with the capricious or malevolent forces, both within the human soul and in the world around us, that can destroy our lives.

La Fontaine’s Fables (published from 1668 to 1694), the most famous retellings and adaptations of the lost original tales of Aesop, can be seen in this light: stories ostensibly about animals can amusingly, disturbingly and above all memorably reveal realities about the human character. The ant and the grasshopper, the wolf and the lamb, the fox and the grapes are just a few examples from La Fontaine’s first book.

At the end of this golden age of French literature came the first European translation of the 1001 Nights, an extraordinary collection of tales whose origins are perhaps in India, whose mature form and famous framing narrative are from Persia and whose surviving texts are in Arabic, compiled in the legendary Baghdad of Haroun-al Rashid long before its destruction by the Mongols in the 13th century.

Rather surprisingly, Antoine Galland’s French version (1707) contained several tales that are today among the most famous in the whole collection, at least among Western readers, but which did not exist in the Arabic manuscripts. These include Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves and Aladdin and his lamp. They were not, however, Galland’s inventions, as a label in the GoMA exhibition implies, but orally transmitted Arabic tales he learnt from his Syrian collaborator, Hanna Diyab, and belong to the same folktale tradition that produced the rest of the collection.

Between these adaptations of ancient and oriental classics, however, there was something even more surprising in Charles Perrault’s collection of fairytales, Les Contes de ma mère l’oie, Mother Goose Fairy Tales (1697). Perrault was a central figure in contemporary French culture. His brother, Claude Perrault, was a distinguished architect who designed the present façade of the Louvre after Louis XIV rather sensationally rejected Bernini’s proposal.

Charles Perrault himself was the right-hand man of Colbert, who was the closest thing to Louis’s effective prime minister, although officially no such position existed, since the king prided himself on conducting the government of the nation personally. Colbert, under Louis’s direction, actively managed national artistic, cultural and intellectual policy, and Perrault was his chief executive in all of these fields, supervising everything from the Academy of Painting to the Académie française. He also composed a didactic poem, La Peinture, celebrating the work of Charles Le Brun (1668). It seems a long way from these responsibilities and interests to the proto-anthropological gathering of folktales, but this is just another illustration of the complexities of the Grand siècle.

In any case, Perrault’s collection included some of the most famous of all fairytales, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Little Red Riding Hood, Puss in Boots and Bluebeard. His book was first translated into English in 1729.

This was only the beginning of the formation of the modern repertoire of fairytales. It is less surprising to find authors interested in such stories at the end of the 18th and during the 19th centuries, periods when anthropology began to develop as a discipline, inspired by the Romantic discovery of a new concept of “culture”. The same interest in popular culture inspired a new interest in Celtic and Germanic mythologies and folktales of all kinds.

The most important figures in this period were the Brothers Grimm and a little later Hans Christian Andersen. Jacob (1785-1863) and Wilhelm (1786-1859) Grimm were collectors of folklore and linguists deeply concerned with German tradition, even though they included Perrault’s stories in their first collection of tales (1812); among the new stories they introduced in this and many subsequent editions were Rapunzel, Snow White and Hansel and Gretel. Andersen (1805-75), born in Denmark, produced his first collections of stories in 1835-37, including The Princess and the Pea, The Emperor’s New Clothes and The Little Mermaid.

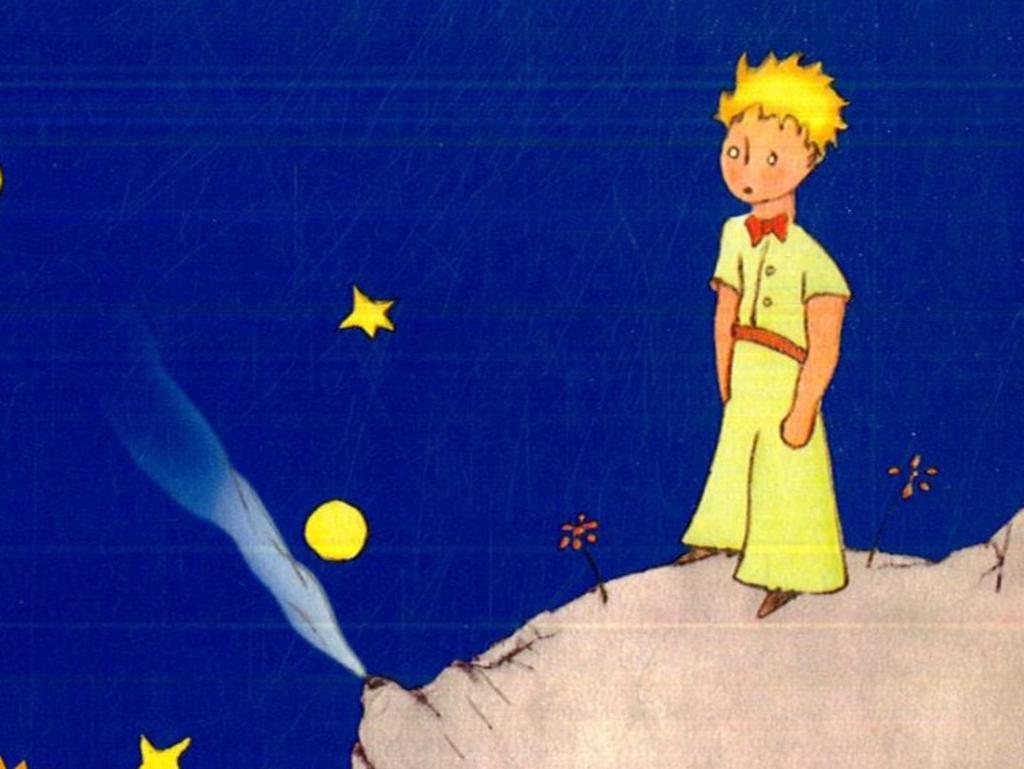

Quite apart from these authors who essentially collected folktales, there are those who invented new stories, among whom Lewis Carroll stands out for the unique genius of his Alice stories, whose enigmatic quality has continued to fascinate and inspire children, philosophers and filmmakers ever since. Another distinctive set of new fairytales was composed by Oscar Wilde, initially as stories he told his sons, and an even more influential quasi-fairytale world was developed over a series of books by CS Lewis. We could include Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince (1943), which, as we saw earlier this year, was by far the most frequently translated book of the 20th century. More recently there have been countless children’s books, such as Where the Wild Things Are, also included in the Fairytales exhibition at GoMA.

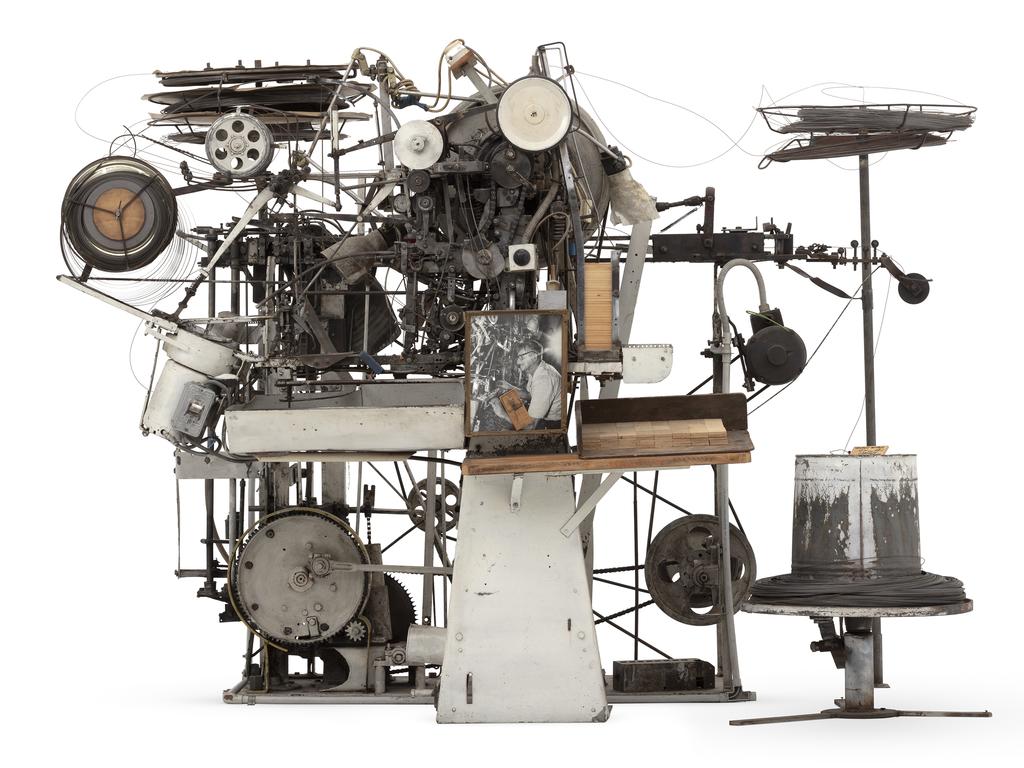

The most memorable thing in this exhibition – although oddly different from everything that follows – is the remarkable installation at the entrance by Brazilian artist Henrique Oliveira. We enter by a sort of maze that begins with featureless white walls; but then we discover that the walls turn into panelling, and then the panelling itself almost at once begins to grow, to transform, to extrude into thrusting organic forms – as though the timber were coming back to life – ending up as a tangle of forms like tree trunks and branches.

The work mimics the fairytale motif of leaving civilisation and going into the woods, and finding that nature does not always behave according to what we believe to be its laws. This is followed by a room devoted to the story of Beauty and the Beast, with projections on the curtained walls of what is perhaps the greatest film ever made about a fairytale, Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et la bête (1946) – a work that draws on an 18th-century tale, combining timeless themes of beauty, goodness and love with a ballast of social realism about wealth and poverty and a powerful vein of darker themes, from the malice of the sisters to the greed of Avenant and the suffering of the Beast in his enchanted form.

Much of the rest of the exhibition is devoted to film adaptations of fairytales, which becomes particularly a pretext for exhibiting sets of original costumes from the productions, often with clips of the original films. All of this is well displayed, entertaining and appealing to people who like costumes and dresses, perhaps particularly mothers bringing children to see a largely family-friendly summer exhibition.

Accordingly, there is only one really dark work in the show, even though fairytales, precisely because they are rooted in the folktales of simple and illiterate people, often deal with quite sinister and frightening themes of death, violence, loss, family tensions, etc; most modern readers are barely aware of the original folk versions of many of these stories, before they were progressively rewritten and tidied up, first by 19th-century editors and then by their 20th-century successors. No doubt contemporary versions are even more sanitised, at a time when publishers don’t think that anyone can be called “fat” or “stupid” in a children’s book.

Speaking of books, it is surprising that there is no display of historical and modern editions of fairytales, particularly looking at the changing style of illustration. It is also odd that there are no Disney films in this exhibition. Instead there are various installations, some thoughtful, such as the collapsed coach or a witch’s house, others by the usual suspects from the commercial and gimmicky end of contemporary art.

The witch’s house is one of the most intriguing installations in the exhibition, although it is more evocative than actually scary; once again it suggests a kind of organic world proliferating and transforming in a way that escapes rational understanding; inside, the complexity of forms is even more absorbing, as though we had entered a living creature.

There are inevitably some wall labels trying to deal with the problem of stereotypes about women of all ages, from little girls to adolescents of marriageable age to old crones and of course witches. But there is of course little point scolding illiterate peasants for thinking in a simplistic way, especially since, in the world from which these stories emerged, what we see as stereotypes corresponded to ineluctable realities of a woman’s life – the vulnerability of girlhood, the need to find a good husband, the sadness and perils of being widowed or, worse, remaining unmarried.

In fact, it is interesting to reflect on the different roles of the two sexes in fairytales and folktales more generally. The stories of boys are relatively simple; they grow up, and then either face some kind of challenge or go on a journey that entails challenges, and they either prove themselves or fail to do so. But for girls, each stage is more complex and they are both more vulnerable and more dependent on relations with their parents, siblings (hence the recurrent theme of jealous sisters) and, later, husband.

The prominence of women and girls in fairytales also reflects universal popular beliefs about the powers of the feminine, both for good and evil. One thing that is perhaps particularly striking here is the special role of the young, pre-adolescent girl, who is epitomised in Lewis Carroll’s figure of Alice. Precisely because she is not yet nubile or drawn into the world of adult women, she seems to have a special capacity for wonder, and to play a quasi-mediumistic role in relation to the mysteries of life.

This is the quality that is particularly captured in a touching series of pictures by Polyxena Papapetrou, in which she photographed her own daughter in the role of Alice, against backgrounds painted by her husband, Robert Nelson. The combination of the would-be real – but play-acting – and the manifestly unreal captures something of the disinterested wonder of Lewis Carroll’s story, which perhaps only a girl of this age could embody.

Fairy tales

QAGoMA to April 28

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout