All the better to see you with: Fairy tales transformed

A new exhibition devoted to fairy tales shows artists trying to make old stories conform to what we want them to say.

Storytelling is, with the painting of images, one of the most ancient and fundamental ways that humans seek to make sense of their world. We can barely imagine its beginnings, in the early and primitive days of the evolution of language, when the story of a hunt or of a legendary ancestor was perhaps evoked in a rudimentary, rhythmic chant around a fire at night. But the audience or participants would already have been fascinated by the most wondrous power of language, which is to make the absent or the departed present again in our imaginations.

This is the very subject of one of the most haunting of later myths: that of Orpheus, the magical singer. We generally think, today, of the tragic love of Orpheus for his wife Eurydice and his descent into the underworld to bring her back: he does obtain her release from death, but is warned that he must not look back at her until he reaches the land of the living. Near the end of his journey, however, he is seized with doubt; he glances back and she vanishes, never to be regained. Orpheus himself is later murdered in obscure circumstances by Thracian maenads.

This version, familiar from poems, paintings and operas, is nonetheless a later development of the story, and there are countless other elaborations, including his participation in the expedition of Jason and the Argonauts. In the earliest core of the myth, though, Orpheus is a magical singer who is torn to pieces by angry maenads, or nature spirits who are later identified as maenads, or followers of Dionysus.

The Orphic myth speaks of the deep but obscure apprehension that the magical power of language transgresses the order of nature, which will ultimately destroy the transgressor. As the story is told and retold in later and literate historical periods, it is updated into the more humanistic form of a love story: but that story still grows from the original core, for bringing back the departed was the very essence of the bard’s power. And yet that return is a kind of illusion that disappears when you look too closely, as Orpheus looked at Eurydice.

The story of Orpheus is thus a kind of meta-myth, a myth about the nature of poetic invention, but it also illustrates the way that myths evolve as they are retold, and indeed if they are retold in a society that is evolving in its understanding of the world. In fact the reason that the Greek myths are so much more significant in world literature and art than, say, the Norse or Celtic ones, is that they deal, in their original and most obscure forms, with deeply important questions, and yet have been elaborated in their telling and retelling, gaining countless layers and nuances of meaning in the process.

There are many kinds of traditional stories, including what we normally consider myths as well as other stories, such as those of the Trojan War, that are usually called legends because they have some historical basis. Fables are short stories with a moral lesson, and finally there are folk and fairy tales, some of which are found across cultures in similar forms, while others are local and regional.

Unlike the great stories of the groups we call myths and legends, folk tales and fairy tales have tended to remain oral traditions, passed on by word of mouth for centuries. The first modern collection of fairy tales was made by a rather unlikely man: Charles Perrault, otherwise best known as the right-hand man of Colbert in administering the arts under Louis XIV, the author of a poem on painting in honour of Le Brun (1668) and of an account of the visit to Paris of Gian Lorenzo Bernini in 1665 (published in 1885).

In 1697, in his retirement, Perrault published Histoires ou contes du temps passe, subtitled Les Contes de ma mere l’Oye, the original Mother Goose fairytales, translated into English in 1729. The first edition included some of the most famous and enduring examples of the genre: Sleeping Beauty, Little Red Riding Hood, Bluebeard, Puss in Boots and Cinderella.

The second great collection of fairytales came more than a century later, in the romantic period, as part of a much broader interest in folk culture, for the very idea of culture in the modern anthropological sense was an invention of this period, and a reaction to the universal conception of rights and values of the Enlightenment. The Brothers Grimm brought out their first volume of fairytales in 1812, with a second in 1815, and a succession of new editions until the middle of the century, in the course of which new stories were added, some old ones dropped, and many of them modified, often to make the originals less violent, terrifying to children or shocking to various moral proprieties.

The most famous of such changes was to the story of Snow White, in which it was originally the mother who was obsessed with the preservation of her own beauty and mortally jealous of her maturing daughter. This horrifying scenario, like a monstrous extrapolation of barely conscious and inadmissible anxieties in the minds of many mothers of a certain age, was replaced by the more superficially plausible and above all palatable figure of the wicked stepmother.

Equally interesting, if less dramatic, were the changes made to the story of Little Red Riding Hood, originally told by Perrault in a much shorter version, presumably close to the original folk tale attested from the early Middle Ages, in which both the grandmother and the little girl were eaten by the wolf. The Grimm brothers rewrote the tale in several variations, but in essence both grandmother and little girl are saved either by the help of a huntsman or by their own resourcefulness.

These changes were made as traditional folk tales, which were originally a means for illiterate peasants to give voice to dark fears and apprehensions, were adapted to the requirements of literate modern readers and to the requirements of middle-class 19th-century morality, so that the good should be rewarded and the wicked punished, and inappropriate matters, such as sexuality, not mentioned at all.

The exhibition currently showing at Melbourne’s Ian Potter Museum, All the better to see you with: Fairy tales transformed, takes its title from the story of Red Riding Hood. It is devoted to modern interpretations of fairytales, and essentially continues the process of adaptation and rewriting, once again to make old stories conform to contemporary moral exigencies, to say what we want them to say and to ignore the inconvenient things that we don’t want to hear.

The earliest works in the exhibition are a series of short films made by Lotte Reiniger (1899-1981) using cut-out silhouettes as shadow-puppets, filmed in stop-motion animation. The results are charming and decorative, but what Bertolt Brecht might have called the “estrangement effect” of this highly artificial medium confers a kind of distance on the stories, with the slow and emblematic quality of dreams.

The earliest of these films, Cinderella, was made in 1922, when Reiniger was only 23 years old, and is full of freshness and wit, particularly inventive in the way that gait, attitude and the movement of heads and limbs — in other words, traditional resources of puppetry — are used for expressive effect.

Reiniger and her husband and collaborator Carl Koch made many other films, in spite of spending 10 years as exiles from Hitler’s Germany, but the other films included in the exhibition, Hansel and Gretel, Sleeping Beauty and Aladdin, were produced in the late 1950s in London. The sense of traditional storytelling is enhanced by the use of a narrative voice rather than dramatic dialogue.

Of the more recent adaptations, the most powerful and imaginatively evocative are elaborately staged and surreal photographs by a Japanese artist, Miwa Yanagi, whose work is not surprisingly used to illustrate the exhibition on the website, with an image of Gretel biting the withered hand of the witch, reaching to her through the bars of a cage. Here, as in Yanagi’s other images, the old tales have been re-imagined through a Japanese sensibility that is uniquely fascinated by ghost and horror stories.

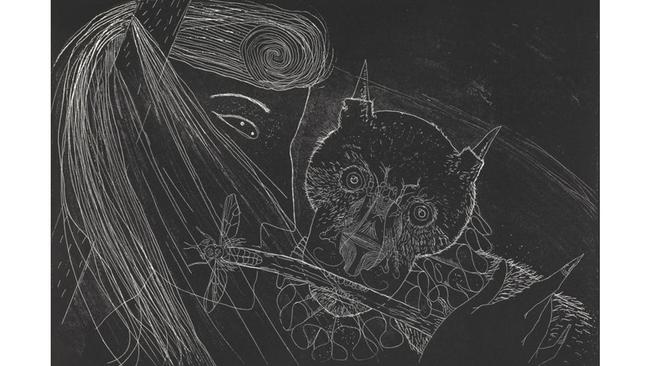

Polyxeni Papapetrou’s images also have something of the disconcerting sense of wonder and strangeness that belongs to these stories, and perhaps the most intriguing pieces are in print media, which offer the possibility of dense and inventive imagery; thus Peter Ellis overlays witty, whimsical and surreal motifs as in a dream. The exhibition also includes a selection of books of fairytales from the University of Melbourne’s Rare Books collection.

On the other hand, much of the other work struggles to connect with the deeper and more terrifying resonances of fairy tales. Amanda Marburg’s pictures chronicle various versions of the Grimm fairytales, including some that were cut from later editions, but her choice of medium, apparently painting from photographs of Plasticine models, while interesting as a proposition, seems to have a weak link in the last stage, between photograph and painting, where the copying feels too mechanical.

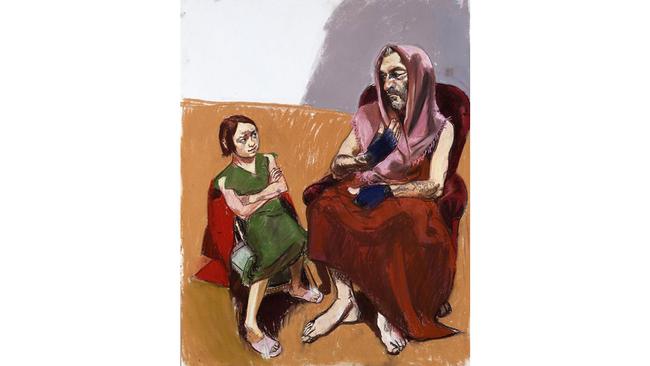

Paula Rego’s series devoted to the story of Little Red Riding Hood illustrates her abilities as a contemporary realist painter, but is painfully obvious and heavy-handed in its attempt at a feminist re-reading of the story. It was hardly necessary to replace the wolf with a man, for Perrault had already explicitly stated in the verse moral appended to the original story that the wolf was code for men who prey on vulnerable girls.

The depth of bathos is reached with Dina Goldstein’s photomontages in which she labours the point that stories don’t always end with a happily-ever-after. Instead, we see our heroines enduring domestic drudgery in the company of the erstwhile Prince Charming or else sinking into hopeless alcoholism. It says a lot about the contemporary art world — and the blank cheque of feminist ideology — that someone can spin a career out of such a mixture of banality and self-pity.

As I suggested above, modern retellings of fairytales seem forever to be trying to adapt them to contemporary versions of what is morally acceptable. For the Victorians, it was above all trying to suppress the unspeakable and to reassert a moral balance of appropriate rewards and punishments, resulting in more-or-less happy endings.

Today, it is another kind of moral censorship: criticising the depiction of women, insisting on asserting a more active role for them, resisting the conventional idea that their story may effectively end with finding a companion in life.

Everyone wants to make fairytales into moral and moralising narratives, but they are inherently something quite different. They are not about what things ought to be like, but about what they are like, including disturbing traits of children, men and women, and often irrational instincts, desires and dreads.

All the better to see you with: Fairy tales transformed

Ian Potter Museum. Until March 4.