Ever wondered what it’s like inside a volcano?

This remarkable installation deep underground at MONA in Hobart is the work of the singer Jónsi from the group Sigur Rós.

Human beings have no doubt always wondered at volcanoes, mountains that mysteriously emit smoke and fire and lava, as though emerging from the belly of the earth itself. These phenomena have given rise to various myths, such as the story that deep below Mt Etna lay the smithy in which the Cyclopes forged the lightning-bolts of Zeus. In an even older story, Etna’s volcanic activity was attributed to the fire-breathing monster Typho, subdued by Zeus and chained beneath the three-cornered island of Sicily.

Volcanoes inspire terror, too, but only sporadically, since there are usually long intervals between significant eruptions. Vesuvius had been dormant for so long that no-one realised that it was a volcano until it exploded in 79 AD, destroying Pompeii and Herculaneum. In Sicily, the city of Catania, briefly renamed Aetna in the fifth century BC, stands at the foot of the volcano and has been destroyed several times in its history; yet the people of Catania love Etna and think of the mountain as their mother, albeit a sometimes cruel and angry one.

Over the centuries, disastrous volcanic eruptions, like earthquakes and other natural catastrophes, have often been interpreted as expressing the anger of the gods but, from the romantic period, they acquired a new significance both as sublime natural phenomena and as metaphors for a new awareness of the dark and unconscious forces in the human heart that had not been banished by enlightenment rationality.

This was the heroic age of modern vulcanology, and Mt Vesuvius obligingly erupted in 1779 and 1794, in time to be studied by scholars such as Sir William Hamilton, painted by Joseph Wright of Derby, and visited by countless grand tourists (including Goethe in 1787), who would be taken by guides to observe lava flows from just metres away.

Volcanoes are no less dramatic and dangerous today, as a number of incidents in recent decades have reminded us. But those of Iceland in particular have been a cause of concern far beyond their own region. In April 2010, smoke and ash from the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull closed many of the airports of Europe for a couple of weeks.

This is the inspiration for a remarkable installation at MONA in Hobart (the other important exhibition at MONA, Heavenly Beings, will be discussed here next week). Hrafntinna is Icelandic for obsidian, the volcanic glass that can be produced by the extremes of heat and pressure in the heart of a volcano, and which was a highly-prized item of trade already in antiquity because of its unique hardness and sharpness as a blade.

The installation, inspired by the sudden eruption of Fagradalsfjall in 2021 and evoking the unimaginable energy inside a volcano, is the work of the singer Jónsi from the group Sigur Rós, and it is essentially an aural experience. It is also eminently suited to a chamber deep underground at MONA and it would be hard to imagine it being anything like as effective or compelling in a more conventional art gallery environment.

You enter a space that is almost completely black, although illuminated by pulsing flashes of light which are too low to reveal much of your surroundings at first, until your vision gradually adjusts to the darkness. In the centre of this space is a large platform on which you can sit or even lie. You are surrounded by an intense soundscape that is very powerful, yet deep rather than loud; it is not deafening, but it makes the space and the platform itself shake and reverberate with its sonic vibrations.

The composition of the soundscape seems partly mechanical and partly natural; that is, some of the sounds could be imagined as literally the grinding of rock masses against each other while others suggest chains, machinery or spades digging heavy gravel. Hints of human history and industry are woven into a texture of sounds evoking a natural environment and activity that existed long before we came and will no doubt continue long after we are gone.

Meanwhile, as our eyes gradually adapt to the darkness, we realise that we are surrounded by a circular wall composed of hundreds of round speakers, which appear to us momentarily in the light flashes; finally, when our night vision is fully functioning, we realise that these speakers are not actually attached to the wall but suspended around us on a framework of scaffolding.

Remarkably, the day after I visited the installation, the Sundhnukagigar volcano in Iceland erupted; an article in the New York Times described the force of the eruption, while a piece on the BBC website recorded the actual sound produced by the seismic event.

If the romantics were fascinated by the dark forces that lie in the depths of the human heart, beyond the threshold of consciousness, they were also drawn to related themes of the supernatural and of dangerous or malevolent forces that surround us. It is no surprise that the Gothic novel, stories of ghosts and the supernatural, and the genre of horror, all have their origins in this period. And horror is the theme of From the other side at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art. I was looking forward to this exhibition after reviewing several interesting thematic shows at ACCA over the past few years, but this one turned out to be rather disappointing. Few of the works had much impact at the time, and even fewer left any discernible trace in the memory, partly because they were too often conceptually and formally weak as well as insubstantial and self-indulgent in content.

The most memorable of the non-film works was Heather B. Swann’s sculpture of a pair of naked girls sitting on two in a set of three beds; the implication, of course, is of unexplained absence and potential threat. The figures themselves are upright and impassive, with a small but disconcerting detail: their nipples have been replaced by eyes. This is the converse of what Magritte did in his painting Le Viol (1934), where a girl’s face is replaced by a torso, her breasts taking the place of her eyes.

Next to this is another of the better pieces, Suzan’s Pitt’s eight-minute animation Visitation (2011). This short film is not remarkable for its coherence or shape, but it does convey a sense of mental confusion, sliding from whimsical dreaming into terrifying visions of increasing violence and horror; notable scenes are of slaughtered horses moving along a conveyor belt and then a woman being thrust alive into a flaming oven.

The exhibition includes a number of sculptural installations, one in ceramics of fingers with long nails and another in various bits of found metal; there are altered photographic works, and photographically-based paintings, such as those of Maria Kozic.

The most aesthetically coherent work in the exhibition is Tracey Moffatt’s A Haunting, a large and very quiet projection that occupies the far end of the second gallery; although minimal in form and subdued in expressive range, it ends up drawing the viewer to its understated sense of menace.

At the other extreme, perhaps, is Naomi Blacklock’s installation that looks rather like a kind of teepee but is meant to evoke a witch’s hat and is animated by a breathy soundtrack that periodically breaks out into shrieking. The text that accompanies the work is a gem of feminist artspeak, of which the last three lines are beyond parody: “Blacklock claims her use of screaming is ‘deeply rooted in a desperate desire to locate an inclusive and intersectional female experience’, particularly as a conduit for depicting self-determination, freedom and revolt.”

What nonsense can be woven of vacuous polysyllabic clichés!

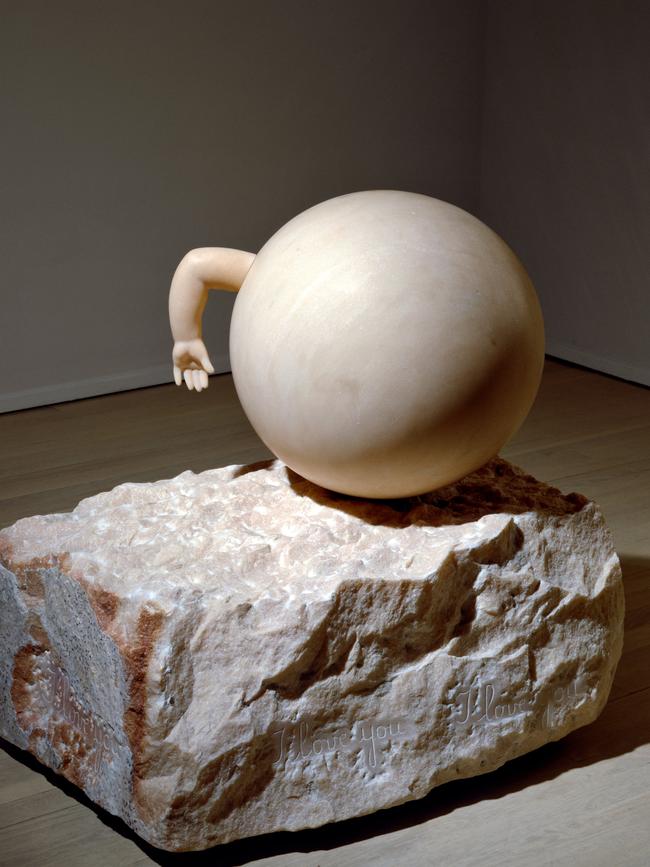

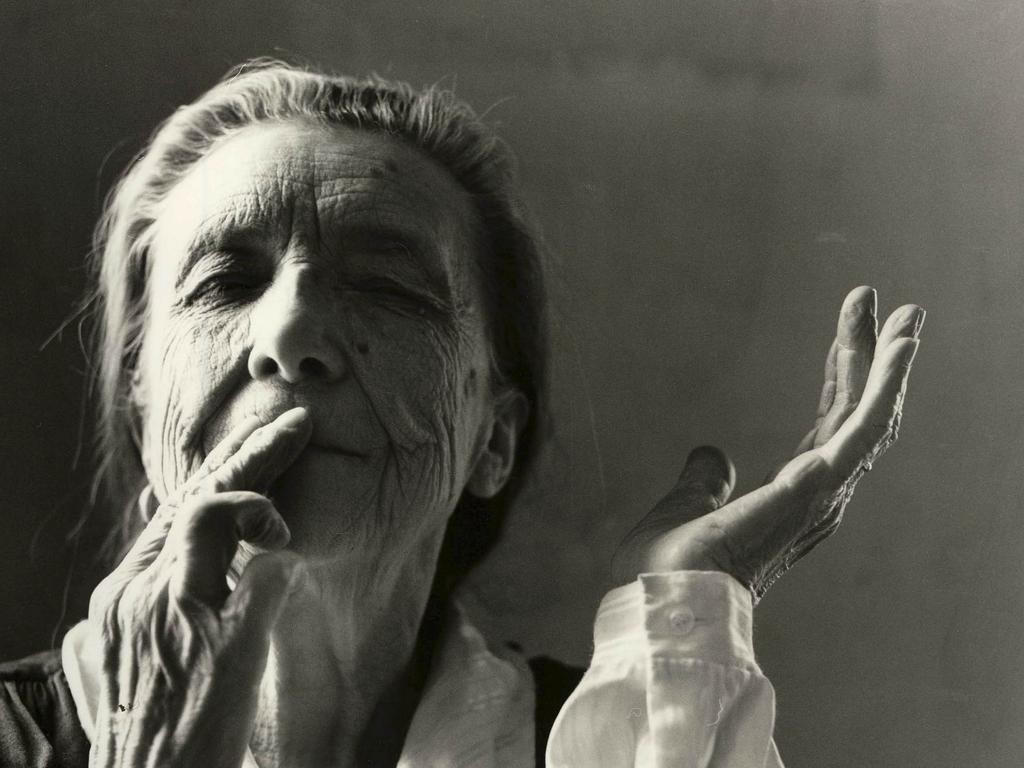

But if this exhibition is a bit of a fizzer in evoking horror, it does perhaps give a valuable clue in approaching the work of the chronically overrated Louise Bourgeois, the subject of a current and of course much-hyped survey at the Art Gallery of NSW, as most readers will know; they may however wonder what else she has actually done beside the monstrous spider that stands outside the gallery and is spoken of with hushed veneration by those in the media who simply repeat the press releases they receive.

I was struck early in the run of the show by an online exchange between two social media friends, both women. The first wrote that she found Bourgeois’ work hard to like; the second replied that it was all about the female experience, as though that was somehow supposed to answer the concerns of the first, or as though it was natural for work that dealt with the female experience to be less appealing.

We may well wonder what there is to like about Bourgeois. It is always rather disturbing when an artist is largely known for a single work, especially one that exists in multiple versions. And indeed, looking closely at her exhibition it is hard not to be struck by the absence of any compelling moment in her art, anything which convincingly demonstrates skill, sensibility, feeling or poetry, and which could then persuade us to follow her into more obscure avenues. In the concurrent Kandinsky exhibition, for example, the joyful energy of the early paintings is irresistible, even if the later pictures may require more effort or trust on our part.

Bourgeois’s early sculptures are tentative and would be entirely forgotten without the retrospective myth-making. Her later works are weak and unfocused, never conveying the sense of a strong and distinct vision. But this is because at no point does her work convey anything like Kandinsky’s joy in the world, love, generosity or transcendence. It is always the neurotic ingrown world that is so well symbolised by the spider that distils poison in its belly.

Is this what the second of my friends meant when she said that Bourgeois’ work is about the female experience?

But surely the female experience cannot be reduced to neurotic self-pity – even if that is what you might imagine from the shrieking witch installation. The implication is that women cannot transcend their own neuroses and reach out with energy and joy to engage with the life of nature, with their fellow-humans and with the spirit; that may be true in the barren world of academic feminist art, imprisoned in a stale atmosphere of recycled ideological thinking, but it certainly is not the case with women artists more generally.

Nonetheless, this may be the key to understanding Louise Bourgeois. She is a mediocre artist artificially raised by the institutional demand for a female “modern master” to a level at which her weakness and inadequacy are inescapably apparent. But the most notable aspect of her sensibility is indeed a kind of horror; not horror inspired by the irresistible power of sublime natural phenomena such as volcanoes, but the poisonous and neurotic horror produced by the festering of narcissism and resentment.

Hrafntinna (Obsidian)

MONA to April 1

From the other side

ACCA to March 3

Louise Bourgeois

AGNSW to April 28

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout